DL Primer

DALL·E 3 Prompt: A rectangular illustration divided into two halves on a clean white background. The left side features a detailed and colorful depiction of a biological neural network, showing interconnected neurons with glowing synapses and dendrites. The right side displays a sleek and modern artificial neural network, represented by a grid of interconnected nodes and edges resembling a digital circuit. The transition between the two sides is distinct but harmonious, with each half clearly illustrating its respective theme: biological on the left and artificial on the right.

Purpose

Why do deep learning systems engineers need deep mathematical understanding of neural network operations rather than treating them as black-box components?

Modern deep learning systems rely on neural networks as their core computational engine, but successful engineering requires understanding the mathematics that governs their behavior. Neural network mathematics determines memory requirements, computational complexity, and optimization landscapes that directly impact system design decisions. Without grasping concepts like gradient flow, activation functions, and backpropagation mechanics, engineers cannot predict system behavior, diagnose training failures, or optimize resource allocation. Each mathematical operation translates to specific hardware requirements: matrix multiplication demands gigabytes per second of memory bandwidth, while activation function choices determine mobile processor compatibility. Understanding these operations transforms neural networks from opaque components into predictable, engineerable systems.

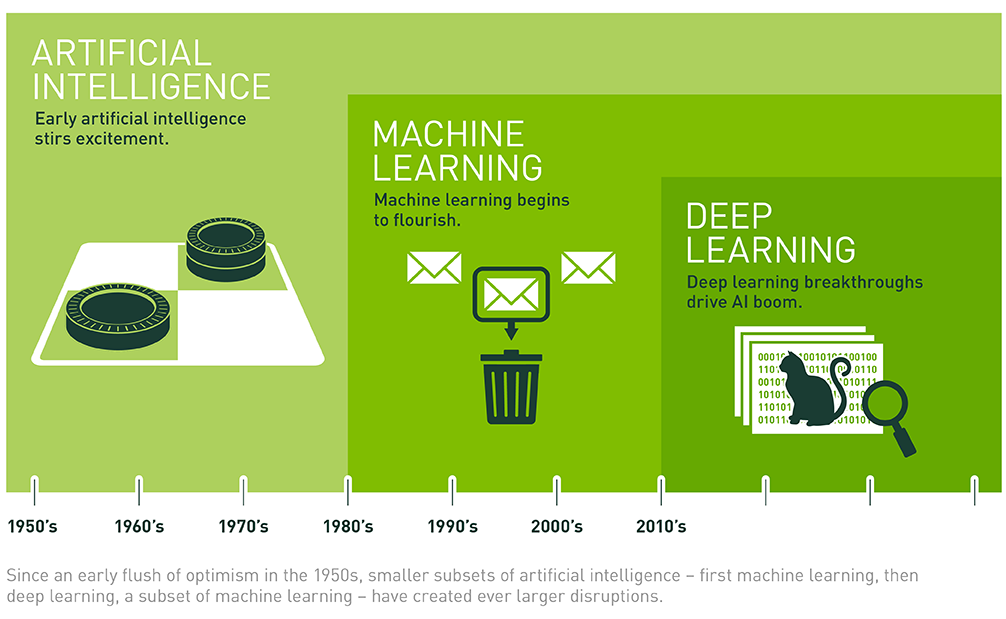

Trace AI evolution from rule-based systems to neural networks and identify driving engineering challenges

Analyze neural network operations (matrix multiplication, activations, gradients) and their hardware implications

Design neural network architectures by selecting appropriate layer configurations, activation functions, and connection patterns based on computational constraints and task requirements

Implement forward propagation through multi-layer networks, computing weighted sums and applying activation functions to transform raw inputs into hierarchical feature representations

Execute backpropagation algorithms to compute gradients and update network weights, demonstrating how prediction errors propagate backward through network layers

Compare training and inference operational phases, analyzing their distinct computational demands, resource requirements, and optimization strategies for different deployment scenarios

Evaluate loss functions and optimization algorithms, explaining how these choices affect training dynamics, convergence behavior, and final model performance

Assess the deep learning pipeline to identify computational bottlenecks and optimization opportunities

Deep Learning Systems Engineering Foundation

Consider the seemingly simple task of identifying cats in photographs. Using traditional programming, you would need to write explicit rules: look for triangular ears, check for whiskers, verify the presence of four legs, examine fur patterns, and handle countless variations in lighting, angles, poses, and breeds. Each edge case demands additional rules, creating increasingly complex decision trees that still fail when encountering unexpected variations. This limitation, the impossibility of manually encoding all patterns for complex real-world problems, drove the evolution from rule-based programming to machine learning.

Deep learning represents the culmination of this evolution, solving the cat identification problem by learning directly from millions of cat and non-cat images. Instead of programming rules, we provide examples and let the system discover patterns automatically. This shift from explicit programming to learned representations has implications for how we design and engineer computational systems.

Deep learning systems present an engineering challenge that distinguishes them from conventional software. While traditional systems execute deterministic algorithms based on explicit rules, deep learning systems operate through mathematical processes that learn data representations. This shift requires understanding the mathematical operations underlying these systems for engineers responsible for their design, implementation, and maintenance.

The engineering implications of this mathematical complexity are important. When production systems exhibit degraded performance characteristics, conventional debugging methodologies prove inadequate. Performance anomalies may originate from gradient instabilities1 during optimization, numerical precision limitations in activation computations, or memory access patterns inherent to tensor operations2. Without foundational mathematical literacy, systems engineers cannot effectively differentiate between implementation failures and algorithmic constraints, accurately predict computational resource requirements, or systematically optimize performance bottlenecks that emerge from the underlying mathematical operations.

1 Gradient Instabilities: In deep networks, gradients can explode (becoming exponentially large) or vanish (becoming exponentially small) as they propagate through layers. Exploding gradients cause training instability with loss values jumping erratically, while vanishing gradients prevent early layers from learning effectively. These issues manifest as system problems—training that appears to “hang” or models that seem to learn slowly despite adequate computational resources.

2 Tensor Operations: Multi-dimensional array operations that form the computational backbone of neural networks. A tensor is an n-dimensional generalization of vectors (1D) and matrices (2D)—for example, a color image is a 3D tensor (height × width × color channels). Modern neural networks operate on 4D+ tensors representing batches of multi-channel data, requiring specialized memory layouts and arithmetic operations optimized for parallel hardware like GPUs and TPUs.

Deep learning has become the dominant approach in modern artificial intelligence by addressing the limitations that constrained earlier methods. While rule-based systems required exhaustive manual specification of decision pathways and conventional machine learning techniques demanded feature engineering expertise, neural network architectures discover pattern representations directly from raw data. This capability enables applications previously considered intractable, though it introduces computational complexity that requires reconsideration of system architecture design principles. As illustrated in Figure 1, neural networks form a foundational component within the broader hierarchy of machine learning and artificial intelligence.

The transition to neural network architectures represents a shift that goes beyond algorithmic evolution, requiring reconceptualization of system design methods. Neural networks execute computations through massively parallel matrix operations that work well with specialized hardware architectures. These systems learn through iterative optimization processes that generate distinctive memory access patterns and impose strict numerical precision requirements. The computational characteristics of inference differ substantially from training phases, requiring distinct optimization strategies for each operational mode.

This chapter establishes the mathematical literacy needed for engineering neural network systems effectively. Rather than treating these architectures as opaque abstractions, we examine the mathematical operations that determine system behavior and performance. We investigate how biological neural processes inspired artificial neuron models, analyze how individual neurons compose into complex network topologies, and explore how these networks acquire knowledge through mathematical optimization. Each concept connects directly to practical system engineering considerations: understanding matrix multiplication operations illuminates memory bandwidth requirements, comprehending gradient computation mechanisms explains numerical precision constraints, and recognizing optimization dynamics informs resource allocation decisions.

We begin by examining how artificial intelligence methods evolved from explicit rule-based programming to adaptive learning systems. We then investigate the biological neural processes that inspired artificial neuron models, establish the mathematical framework governing neural network operations, and analyze the optimization processes that enable these systems to extract patterns from complex datasets. Throughout this exploration, we focus on the system engineering implications of each mathematical principle, constructing the theoretical foundation needed for designing, implementing, and optimizing production-scale deep learning systems.

Upon completion of this chapter, students will understand neural networks not as opaque algorithmic constructs, but as engineerable computational systems whose mathematical operations provide direct guidance for their practical implementation and operational deployment.

Evolution of ML Paradigms

To understand why deep learning emerged as the dominant approach requiring specialized computational infrastructure, we examine how AI methods evolved over time. The current era of AI represents the latest stage in evolution from rule-based programming through classical machine learning to modern neural networks. Understanding this progression reveals how each approach builds upon and addresses the limitations of its predecessors.

Traditional Rule-Based Programming Limitations

Traditional programming requires developers to explicitly define rules that tell computers how to process inputs and produce outputs. Consider a simple game like Breakout3, shown in Figure 2. The program needs explicit rules for every interaction: when the ball hits a brick, the code must specify that the brick should be removed and the ball’s direction should be reversed. While this approach works effectively for games with clear physics and limited states, it demonstrates a limitation of rule based systems.

3 Breakout: The classic 1976 arcade game by Atari became historically significant in AI when DeepMind’s DQN (Deep Q-Network) learned to play it from pixels alone in 2013, achieving superhuman performance without any programmed game rules. This breakthrough demonstrated that neural networks could learn complex strategies purely from raw sensory input and reward signals, marking a crucial milestone in deep reinforcement learning that influences modern AI game-playing systems.

Beyond individual applications, this rule based paradigm extends to all traditional programming, as illustrated in Figure 3. The program takes both rules for processing and input data to produce outputs. Early artificial intelligence research explored whether this approach could scale to solve complex problems by encoding sufficient rules to capture intelligent behavior.

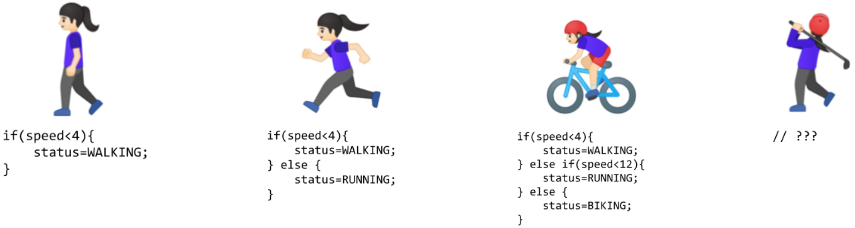

Despite their apparent simplicity, rule-based limitations become evident with complex real-world tasks. Recognizing human activities (Figure 4) illustrates this challenge: classifying movement below 4 mph as walking seems straightforward until real-world complexity emerges. Speed variations, transitions between activities, and boundary cases each demand additional rules, creating unwieldy decision trees. Computer vision tasks compound these difficulties: detecting cats requires rules about ears, whiskers, and body shapes, while accounting for viewing angles, lighting, occlusions, and natural variations. Early systems achieved success only in controlled environments with well-defined constraints.

Recognizing these limitations, the knowledge engineering approach that characterized artificial intelligence research in the 1970s and 1980s attempted to systematize rule creation. Expert systems4 encoded domain knowledge as explicit rules, showing promise in specific domains with well defined parameters but struggling with tasks humans perform naturally, such as object recognition, speech understanding, or natural language interpretation. These limitations highlighted a challenge: many aspects of intelligent behavior rely on implicit knowledge that resists explicit rule based representation.

4 Expert Systems: Rule-based AI programs that encoded human domain expertise, prominent from 1970-1990. Notable examples include MYCIN (Stanford, 1976) for medical diagnosis, which outperformed human doctors in some antibiotics selection tasks, and XCON (DEC, 1980) for computer configuration, which saved the company $40 million annually. Despite early success, expert systems required extensive manual knowledge engineering—extracting and encoding rules from human experts—and struggled with uncertainty and common-sense reasoning that humans handle naturally.

Classical Machine Learning

Confronting the scalability barriers of rule based systems, researchers began exploring approaches that could learn from data. Machine learning offered a promising direction: instead of writing rules for every situation, researchers could write programs that identified patterns in examples. However, the success of these methods still depended heavily on human insight to define relevant patterns, a process known as feature engineering.

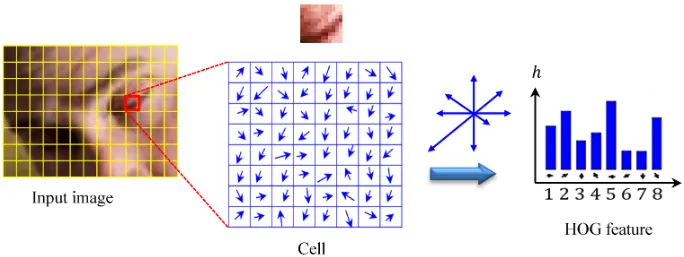

This approach introduced feature engineering: transforming raw data into representations that expose patterns to learning algorithms. The Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) (Dalal and Triggs, n.d.)5 method (Figure 5) exemplifies this approach, identifying edges where brightness changes sharply, dividing images into cells, and measuring edge orientations within each cell. This transforms raw pixels into shape descriptors robust to lighting variations and small positional changes.

5 Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG): Developed by Navneet Dalal and Bill Triggs in 2005, HOG became the gold standard for object detection before deep learning. It achieved near-perfect accuracy on pedestrian detection—a breakthrough that enabled practical computer vision applications. HOG works by computing gradients (edge directions) in 8×8 pixel cells, then creating histograms of 9 orientation bins. This clever abstraction captures object shape while ignoring texture details, making it robust to lighting changes but requiring expert knowledge to design.

Complementary methods like SIFT (Lowe 1999)6 (Scale-Invariant Feature Transform) and Gabor filters7 captured different visual patterns—SIFT detected keypoints stable across scale and orientation changes, while Gabor filters identified textures and frequencies. Each encoded domain expertise about visual pattern recognition.

6 Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT): Invented by David Lowe at University of British Columbia in 1999, SIFT revolutionized computer vision by detecting “keypoints” that remain stable across different viewpoints, scales, and lighting conditions. A typical image yields 1,000-2,000 SIFT keypoints, each described by a 128-dimensional vector. Before deep learning, SIFT was the backbone of applications like Google Street View’s image matching and early smartphone augmented reality. The algorithm’s 4-step process (scale-space extrema detection, keypoint localization, orientation assignment, and descriptor generation) required deep expertise to implement effectively.

7 Gabor Filters: Named after Dennis Gabor (1971 Nobel Prize in Physics for holography), these mathematical filters detect edges and textures by analyzing frequency and orientation simultaneously. Used extensively in computer vision from 1980-2010, Gabor filters mimic how the human visual cortex processes images—different neurons respond to specific orientations and spatial frequencies. A typical Gabor filter bank contains 40+ filters (8 orientations × 5 frequencies) to capture texture patterns, making them ideal for applications like fingerprint recognition and fabric quality inspection before deep learning made manual filter design obsolete.

These engineering efforts enabled advances in computer vision during the 2000s. Systems could now recognize objects with some robustness to real world variations, leading to applications in face detection, pedestrian detection, and object recognition. Despite these successes, the approach had limitations. Experts needed to carefully design feature extractors for each new problem, and the resulting features might miss important patterns that were not anticipated in their design.

Deep Learning: Automatic Pattern Discovery

Neural networks represent a shift in how we approach problem solving with computers, establishing a new programming approach that learns from data rather than following explicit rules. This shift becomes particularly evident when considering tasks like computer vision, specifically identifying objects in images.

Deep learning differs by learning directly from raw data. Traditional programming, as we saw earlier in Figure 3, required both rules and data as inputs to produce answers. Machine learning inverts this relationship, as shown in Figure 6. Instead of writing rules, we provide examples (data) and their correct answers to discover the underlying rules automatically. This shift eliminates the need for humans to specify what patterns are important.

Through this automated process, the system discovers these patterns from examples. When shown millions of images of cats, the system learns to identify increasingly complex visual patterns, from simple edges to more complex combinations that make up cat like features. This parallels how human visual systems operate, building understanding from basic visual elements to complex objects.

Building on this hierarchical learning principle, deep networks learn hierarchical representations where complex patterns emerge from simpler ones. Each layer learns increasingly abstract features: edges → shapes → objects → concepts. Deeper networks can express exponentially more functions with only polynomially more parameters, which is why “deep” matters theoretically. The compositionality principle explains why deep learning works: complex real-world patterns often have hierarchical structure that matches the network’s representational bias.

This hierarchical structure creates an advantage: unlike traditional approaches where performance plateaus, deep learning models continue improving with additional data (recognizing more variations) and computation (discovering subtler patterns). This scalability drove dramatic performance gains. Image recognition accuracy improved from 74% in 2012 to over 95% today8.

8 ImageNet Competition Progress: The ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) tracked computer vision progress from 2010-2017. Error rates dropped dramatically: traditional methods achieved ~28% error in 2010, AlexNet (Krizhevsky, Sutskever, and Hinton 2017) (first deep learning winner) achieved 15.3% in 2012, and ResNet (He et al. 2016) achieved 3.6% in 2015—surpassing estimated human performance of 5.1%. This rapid improvement demonstrated deep learning’s superiority over hand-crafted features, triggering the modern AI revolution. The competition ended in 2017 when further improvements became incremental.

Neural network performance follows predictable scaling relationships that directly impact system design. These scaling laws explain why modern AI systems prioritize larger models over longer training: GPT-4 has ~1000× more parameters than GPT-1 but uses similar training time. Memory bandwidth and storage capacity consequently become the primary constraints rather than raw computational power. The detailed mathematical formulations of these scaling laws and their quantitative analysis are covered in Chapter 8: AI Training, while Chapter 10: Model Optimizations explores their practical implementation.

Beyond performance improvements, this approach has implications for AI system construction. Deep learning’s ability to learn directly from raw data eliminates the need for manual feature engineering while introducing new demands. Advanced infrastructure is required to handle massive datasets, powerful computers to process this data, and specialized hardware to perform complex mathematical calculations efficiently. The computational requirements of deep learning have driven the development of specialized computer chips optimized for these calculations.

The empirical evidence strongly supports these claims. The success of deep learning in computer vision exemplifies how this approach, when given sufficient data and computation, can surpass traditional methods. This pattern has repeated across many domains, from speech recognition to game playing, establishing deep learning as a transformative approach to artificial intelligence.

However, this transformation comes with trade-offs: deep learning’s computational demands reshape system requirements. Understanding these requirements provides context for the technical details of neural networks that follow.

Computational Infrastructure Requirements

The progression from traditional programming to deep learning represents not just a shift in how we solve problems, but a transformation in computing system requirements that directly impacts every aspect of ML systems design. This transformation becomes important when we consider the full spectrum of ML systems, from massive cloud deployments to resource constrained Tiny ML devices.

Traditional programs follow predictable patterns. They execute sequential instructions, access memory in regular patterns, and use computing resources in well understood ways. A typical rule based image processing system might scan through pixels methodically, applying fixed operations with modest and predictable computational and memory requirements. These characteristics made traditional programs relatively straightforward to deploy across different computing platforms.

| System Aspect | Traditional Programming | ML with Features | Deep Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computation | Sequential, predictable paths | Structured parallel operations | Massive matrix parallelism |

| Memory Access | Small, predictable patterns | Medium, batch-oriented | Large, complex hierarchical patterns |

| Data Movement | Simple input/output flows | Structured batch processing | Intensive cross-system movement |

| Hardware Needs | CPU-centric | CPU with vector units | Specialized accelerators |

| Resource Scaling | Fixed requirements | Linear with data size | Exponential with complexity |

As we moved toward data-driven approaches, classical machine learning with engineered features introduced new complexities. Feature extraction algorithms required more intensive computation and structured data movement. The HOG feature extractor discussed earlier, for instance, requires multiple passes over image data, computing gradients and constructing histograms. While this increased both computational demands and memory complexity, the resource requirements remained predictable and scalable across platforms.

Deep learning, however, reshapes system requirements across multiple dimensions, as illustrated in Table 1. Understanding these evolutionary changes is important as differences manifest in several ways, with implications across the entire ML systems spectrum.

Parallel Matrix Operation Patterns

The computational paradigm shift becomes immediately apparent when comparing these approaches. Traditional programs follow sequential logic flows. In stark contrast, deep learning requires massive parallel operations on matrices. This shift explains why conventional CPUs, designed for sequential processing, prove inefficient for neural network computations.

This parallel computational model creates new bottlenecks. The fundamental challenge is the memory wall: while computational capacity can be increased by adding more processing units, memory bandwidth to feed those units doesn’t scale as favorably9. Modern accelerators address this through hierarchical memory systems with multiple cache levels and specialized memory architectures that enable data reuse. The key insight is that keeping data close to where it’s processed—in faster, smaller caches rather than slower, larger main memory—dramatically improves performance.

9 Memory Hierarchy Performance: Modern processors employ multiple memory levels with vastly different access speeds. L1 cache (the fastest, closest to processor) provides data in 1-2 processor clock cycles, L2 cache requires 10-20 cycles, while main memory takes 100+ cycles—creating a 50-100× speed difference. The throughput also varies dramatically: L1 can deliver up to ~1000 GB/s (gigabytes per second), L2 up to ~500 GB/s, while main memory provides only ~100 GB/s on CPUs (~1 TB/s on GPUs with specialized high-bandwidth memory). Neural network accelerators succeed by keeping frequently accessed weights in fast cache and reusing them across many computations, often achieving 80%+ cache hit rates through careful scheduling.

These memory hierarchy challenges explain why neural network accelerators focus on maximizing data reuse. Rather than repeatedly fetching the same weights from slow main memory, successful designs keep frequently accessed data in fast local storage and carefully schedule operations to minimize data movement. The detailed quantitative analysis of these memory systems and their performance characteristics is covered in Chapter 11: AI Acceleration.

The need for parallel processing has driven the adoption of specialized hardware architectures, ranging from powerful cloud GPUs to specialized mobile processors to Tiny ML accelerators. The specific hardware architectures and their trade-offs for ML workloads are explored in Chapter 11: AI Acceleration.

Hierarchical Memory Architecture

The memory requirements present another shift. Traditional programs typically maintain small, fixed memory footprints. In contrast, deep learning models must manage parameters across complex memory hierarchies. Memory bandwidth often becomes the primary performance bottleneck, creating challenges for resource-constrained systems.

This memory-intensive nature creates performance bottlenecks unique to neural computing. Matrix multiplication—the core neural network operation—is often memory bandwidth-bound rather than compute-bound10. The fundamental issue is that processors can perform computations faster than they can fetch data from memory. Each weight must be loaded from memory to perform a multiplication, and if the memory system can’t supply data fast enough, computational units sit idle waiting for values to arrive. This imbalance between computational capability and memory bandwidth explains why simply adding more processing units doesn’t proportionally improve performance.

10 Memory-Bound Operations: Consider a typical matrix multiplication: a processor capable of performing a billion floating-point operations per second requires loading data at 250-500 GB/s (gigabytes per second) to keep computational units fully utilized. However, typical CPU memory bandwidth is only 50-100 GB/s, while even high-end GPUs provide 1-2 TB/s (terabytes per second). This gap means CPUs achieve only 5-15% of peak computational efficiency on neural network operations, while GPUs reach 40-60% through higher bandwidth and better data reuse strategies.

GPUs address this challenge through both higher memory bandwidth and massive parallelism, achieving better utilization than traditional CPUs. However, the underlying constraint remains: energy consumption in neural networks is dominated by data movement, not computation. Moving data from main memory to processing units consumes more energy than the actual mathematical operations. This energy hierarchy explains why specialized processors focus on techniques that reduce data movement, keeping data closer to where it’s processed.

This fundamental memory-computation tradeoff manifests differently across deployment scenarios. Cloud servers can afford more memory and power to maximize throughput, while mobile devices must carefully optimize to operate within strict power budgets. Training systems prioritize computational throughput even at higher energy costs, while inference systems emphasize energy efficiency. These different constraints drive different optimization strategies across the ML systems spectrum, ranging from memory-rich cloud deployments to heavily optimized Tiny ML implementations.

Memory optimization strategies like quantization and pruning are detailed in Chapter 10: Model Optimizations, while hardware architectures and their memory systems are explored in Chapter 11: AI Acceleration.

Distributed Computing Requirements

Researchers discovered deep learning changes how systems scale and the importance of efficiency. Traditional programs have relatively fixed resource requirements with predictable performance characteristics. Deep learning models can consume exponentially more resources as they grow in complexity. This relationship between model capability and resource consumption makes system efficiency a concern. Chapter 9: Efficient AI provides coverage of techniques to optimize this relationship, including methods to reduce computational requirements while maintaining model performance.

Bridging algorithmic concepts with hardware realities becomes essential. While traditional programs map relatively straightforwardly to standard computer architectures, deep learning requires careful consideration of:

- How to efficiently map matrix operations to physical hardware (Chapter 11: AI Acceleration covers hardware-specific optimization strategies)

- Ways to minimize data movement across memory hierarchies

- Methods to balance computational capability with resource constraints (Chapter 9: Efficient AI explores scaling laws and efficiency trade-offs)

- Techniques to optimize both algorithm and system-level efficiency (Chapter 10: Model Optimizations provides model compression techniques)

These shifts explain why deep learning has spurred innovations across the entire computing stack. From specialized hardware accelerators to new memory architectures to sophisticated software frameworks, the demands of deep learning continue to reshape computer system design.

Having established both the historical progression from rule-based systems to neural networks and the computational infrastructure this evolution demands, we now examine the foundational inspiration behind these systems. The answer to what neural networks compute begins not with silicon and software, but with biology—specifically, the neural networks in our brains that inspired the artificial neural networks powering modern AI systems.

From Biology to Silicon

Having examined how programming approaches evolved from rules to data-driven learning, and how this evolution drives the computational infrastructure requirements we see today, we now turn to the question: what are these neural networks actually computing? The answer begins not with silicon, but with biology.

The massive computational requirements we just examined (specialized processors, hierarchical memory systems, high-bandwidth data movement) all trace back to a simple inspiration: the biological neuron. Understanding how nature solves information processing problems with 20 watts of power reveals both the potential and the challenges of artificial neural systems. As we examine biological neurons and their artificial counterparts, watch for a pattern: each biological feature that we choose to implement or approximate creates specific computational demands, linking the dendrite-and-synapse model directly to the processing power and memory bandwidth requirements we just discussed.

This section bridges biological inspiration and systems implementation by examining three key transformations: how biological neurons inspire artificial neuron design, how neural principles translate into mathematical operations, and how these operations drive the system requirements we outlined earlier. By the end, you’ll understand why implementing even simplified neural computation requires the specialized hardware infrastructure modern ML systems demand.

Biological Neural Processing Principles

From a systems perspective, biological neural networks offer solutions to the computational challenges we’ve just discussed: they achieve massive parallelism, efficient memory usage, and adaptive learning while consuming minimal energy. Four key principles from biological intelligence directly inform artificial neural network design:

Adaptive Learning: The brain continuously modifies neural connections based on experience, refining responses through interaction with the environment. This biological capability inspired machine learning’s core principle: improving from data rather than following fixed, pre-programmed rules.

Parallel Processing: The brain processes vast amounts of information simultaneously, with different regions specializing in specific functions while working in concert. This distributed, parallel architecture contrasts with traditional sequential computing and has influenced modern AI system design.

Pattern Recognition: Biological systems excel at identifying patterns in complex, noisy data—recognizing faces in crowds, understanding speech in noisy environments, identifying objects from partial information. This capability has inspired applications in computer vision and speech recognition, though artificial systems still strive to match the brain’s efficiency.

Energy Efficiency: Biological systems achieve processing with exceptional energy efficiency. The human brain’s 20-watt power consumption11 creates a stark efficiency gap that artificial systems are still striving to bridge. Understanding and replicating this efficiency is explored in Chapter 18: Sustainable AI through environmental impact analysis and energy-efficient optimization strategies.

11 Brain Energy Efficiency: The human brain contains approximately 86-100 billion neurons and performs an estimated 10^13 to 10^16 operations per second on just 20 watts—equivalent to running a single LED light bulb. In contrast, training GPT-3 (Brown et al. 2020) consumed about 1,287 megawatt-hours of electricity (Strubell, Ganesh, and McCallum 2019). This stark efficiency gap drives research into neuromorphic computing and inspired the development of specialized AI chips designed to mimic brain-like processing.

These biological principles suggest key requirements for artificial neural systems: simple processing units integrating multiple inputs, adjustable connection strengths, nonlinear activation based on input thresholds, parallel processing architecture, and learning through connection strength modification. The following sections examine how we translate these biological insights into mathematical operations and into silicon implementations.

These biological principles have shaped two approaches in artificial intelligence. The first attempts to directly mimic neural structure and function, creating artificial neural networks that structurally resemble biological networks. The second takes a more abstract approach, adapting biological principles to work efficiently within computer hardware constraints without copying biological structures exactly.

To understand how either approach works in practice, we must first examine the basic unit that makes neural computation possible: the individual neuron. By understanding how biological neurons process information, we can then see how this process translates into the mathematical operations that drive artificial neural networks.

Biological Neuron Structure

Translating these high-level principles into practical implementation requires examining the basic unit of biological information processing: the neuron. This cellular building block provides the blueprint for its artificial counterpart and reveals how complex neural networks emerge from simple components working together.

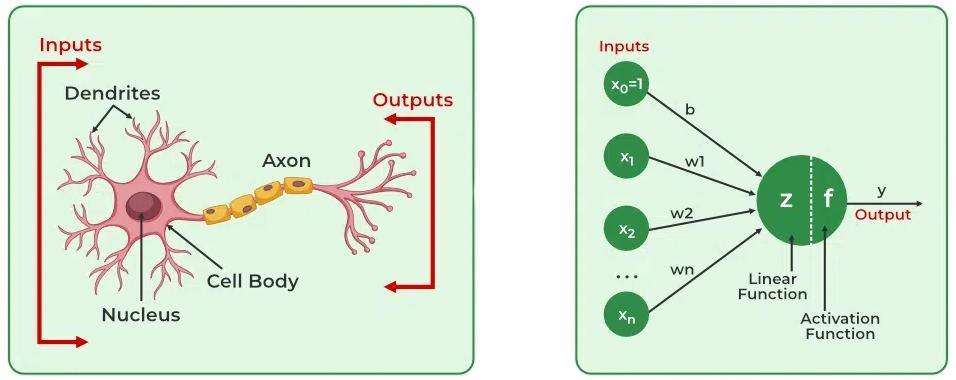

In biological systems, the neuron (or cell) represents the basic functional unit of the nervous system. Understanding its structure is crucial for drawing parallels to artificial systems. Figure 7 illustrates the structure of a biological neuron.

A biological neuron consists of several key components. The central part is the cell body, or soma, which contains the nucleus and performs the cell’s basic life processes. Extending from the soma are branch-like structures called dendrites, which act as receivers for incoming signals from other neurons. The connections between neurons occur at synapses12, which modulate the strength of the transmitted signals. Finally, a long, slender projection called the axon conducts electrical impulses away from the cell body to other neurons.

12 Synapses: From the Greek word “synaptein” meaning “to clasp together,” synapses are the connection points between neurons where chemical or electrical signals are transmitted. A typical neuron has 1,000-10,000 synaptic connections, and the human brain contains roughly 100 trillion synapses. The strength of synaptic connections can change through experience, forming the biological basis of learning and memory—a principle directly mimicked by adjustable weights in artificial neural networks.

Integrating these structural components, the neuron functions as follows: Dendrites act as receivers, collecting input signals from other neurons. Synapses at these connections modulate the strength of each signal, determining how much influence each input has. The soma integrates these weighted signals and decides whether to trigger an output signal. If triggered, the axon transmits this signal to other neurons.

Each element of a biological neuron has a computational analog in artificial systems, reflecting the principles of learning, adaptability, and efficiency found in nature. To better understand how biological intelligence informs artificial systems, Table 2 captures the mapping between the components of biological and artificial neurons. This should be viewed alongside Figure 7 for a complete picture. Together, they show the biological-to-artificial neuron mapping.

| Biological Neuron | Artificial Neuron |

|---|---|

| Cell | Neuron / Node |

| Dendrites | Inputs |

| Synapses | Weights |

| Soma | Net Input |

| Axon | Output |

Understanding these correspondences proves crucial for grasping how artificial systems approximate biological intelligence. Each component serves a similar function through different mechanisms, with specific implications for artificial neural networks.

Cell \(\longleftrightarrow\) Neuron/Node: The artificial neuron or node serves as the basic computational unit, mirroring the cell’s role in biological systems.

Dendrites \(\longleftrightarrow\) Inputs: Dendrites in biological neurons receive incoming signals from other neurons, analogous to how inputs feed into artificial neurons. They act as the signal receivers, like antennas collecting information.

Synapses \(\longleftrightarrow\) Weights: Synapses modulate the strength of connections between neurons, directly analogous to weights in artificial neurons. These weights are adjustable, enabling learning and optimization over time by controlling how much influence each input has.

Soma \(\longleftrightarrow\) Net Input: The net input in artificial neurons sums weighted inputs to determine activation, similar to how the soma integrates signals in biological neurons.

Axon \(\longleftrightarrow\) Output: The output of an artificial neuron passes processed information to subsequent network layers, much like an axon transmits signals to other neurons.

This mapping illustrates how artificial neural networks simplify and abstract biological processes while preserving their essential computational principles. Understanding individual neurons represents only the beginning. The true power of neural networks emerges from how these basic units work together in larger systems.

From a systems engineering perspective, this biological-to-artificial translation reveals why neural networks have such demanding computational requirements. Each simple biological process maps to intensive mathematical operations that must be executed millions or billions of times in parallel.

Artificial Neural Network Design Principles

Bridging the gap from biological inspiration to practical implementation, the translation from biological principles to artificial computation requires a deep appreciation of what makes biological neural networks so effective at both the cellular and network levels, and why replicating these capabilities in silicon presents such significant systems challenges. The brain processes information through distributed computation across billions of neurons, each operating relatively slowly compared to silicon transistors. A biological neuron fires at approximately 200 Hz, while modern processors operate at gigahertz frequencies. Despite this speed limitation, the brain’s parallel architecture enables sophisticated real-time processing of complex sensory input, decision-making, and control of behavior.

Despite the apparent speed disadvantage, this computational efficiency emerges from the brain’s basic organizational principles. Each neuron acts as a simple processing unit, integrating inputs from thousands of other neurons and producing a binary output signal based on whether this integrated input exceeds a threshold. The connection strengths between neurons, mediated by synapses, are continuously modified through experience. This synaptic plasticity forms the basis for learning and adaptation in biological neural networks.

Replicating biological efficiency in artificial systems requires navigating fundamental trade-offs. While the brain achieves remarkable efficiency with only 20 watts (as noted earlier), comparable artificial neural networks require orders of magnitude more power. Large language models, for example, can consume megawatts during training and kilowatts during inference—thousands to hundreds of thousands of times more power than the brain. This substantial efficiency gap drives the engineering focus on specialized hardware, quantization techniques, and architectural innovations.

Drawing from these organizational insights, biological systems suggest several key computational elements needed in artificial neural systems:

- Simple processing units that integrate multiple inputs

- Adjustable connection strengths between units

- Nonlinear activation based on input thresholds

- Parallel processing architecture

- Learning through modification of connection strengths

The question now becomes: how do we translate these abstract biological principles into concrete mathematical operations that computers can execute?

Mathematical Translation of Neural Concepts

Translating biological insights into practical systems, we face the challenge of capturing the essence of neural computation within the rigid framework of digital systems. As established in our neuron model analysis (see Table 2), artificial neurons simplify biological processes into three key operations: weighted input processing (synaptic strength), summation (signal integration), and activation functions (threshold-based firing).

Table 3 provides a systematic view of how these biological features map to their computational counterparts, revealing both the possibilities and limitations of digital neural implementation.

| Biological Feature | Computational Translation |

|---|---|

| Neuron firing | Activation function |

| Synaptic strength | Weighted connections |

| Signal integration | Summation operation |

| Distributed memory | Weight matrices |

| Parallel processing | Concurrent computation |

Using the biological-to-artificial mapping principles outlined earlier, this mathematical abstraction preserves key computational principles while enabling efficient digital implementation. The weighting, summation, and activation operations directly correspond to the synaptic strength, signal integration, and threshold firing mechanisms identified in our neuron correspondence analysis.

This abstraction has a computational cost. What happens effortlessly in biology requires intensive mathematical computation in artificial systems. As discussed in the Memory Systems section, these operations create significant computational demands due to memory bandwidth limitations.

Memory in artificial neural networks takes a markedly different form from biological systems. While biological memories are distributed across synaptic connections and neural patterns, artificial networks store information in discrete weights and parameters. This architectural difference reflects the constraints of current computing hardware, where memory and processing are physically separated rather than integrated as in biological systems. Despite these implementation differences, artificial neural networks achieve similar functional capabilities in pattern recognition and learning.

The brain’s massive parallelism represents a challenge in artificial implementation. While biological neural networks process information through billions of neurons operating simultaneously, artificial systems approximate this parallelism through specialized hardware like GPUs and tensor processing units. These devices efficiently compute the matrix operations that form the mathematical foundation of artificial neural networks, achieving parallel processing at a different scale and granularity than biological systems.

Hardware and Software Requirements

The computational translation of neural principles creates infrastructure demands that emerge from key differences between biological and artificial implementations, directly shaping system design.

Table 4 shows how each computational element drives particular system requirements. This mapping shows how the choices made in computational translation directly influence the hardware and system architecture needed for implementation.

| Computational Element | System Requirements |

|---|---|

| Activation functions | Fast nonlinear operation units |

| Weight operations | High-bandwidth memory access |

| Parallel computation | Specialized parallel processors |

| Weight storage | Large-scale memory systems |

| Learning algorithms | Gradient computation hardware |

Storage architecture represents a critical requirement, driven by the key difference in how biological and artificial systems handle memory. In biological systems, memory and processing are intrinsically integrated—synapses both store connection strengths and process signals. Artificial systems, however, must maintain a clear separation between processing units and memory. This creates a need for both high-capacity storage to hold millions or billions of connection weights and high-bandwidth pathways to move this data quickly between storage and processing units. The efficiency of this data movement often becomes a critical bottleneck that biological systems do not face.

The learning process itself imposes distinct requirements on artificial systems. While biological networks modify synaptic strengths through local chemical processes, artificial networks must coordinate weight updates across the entire network. This creates computational and memory demands during training, as systems must not only store current weights but also maintain space for gradients and intermediate calculations. The requirement to backpropagate error signals, with no real biological analog, complicates the system architecture. Securing these large models and protecting sensitive training data introduces complex requirements addressed in Chapter 16: Robust AI.

Energy efficiency emerges as a final critical requirement, highlighting perhaps the starkest contrast between biological and artificial implementations. The human brain’s remarkable energy efficiency, which operates on approximately 20 watts, stands in sharp contrast to the substantial power demands of artificial neural networks. Current systems often require orders of magnitude more energy to implement similar capabilities. This gap drives ongoing research in more efficient hardware architectures and has profound implications for the practical deployment of neural networks, particularly in resource-constrained environments like mobile devices or edge computing systems. The environmental impact of this energy consumption and strategies for sustainable AI development are explored in Chapter 18: Sustainable AI.

These system requirements directly drive the architectural choices we make in building ML systems, from the specialized hardware accelerators covered in Chapter 11: AI Acceleration to the distributed training systems discussed in Chapter 8: AI Training. Understanding why these requirements exist, rooted in the key differences between biological and artificial computation, is essential for making informed decisions about system design and optimization.

Evolution of Neural Network Computing

We can appreciate how the field of deep learning evolved to meet these challenges through advances in hardware and algorithms. This journey began with early artificial neural networks in the 1950s, marked by the introduction of the Perceptron (Rosenblatt 1958)13. While groundbreaking in concept, these early systems were severely limited by the computational capabilities of their era, primarily mainframe computers that lacked both the processing power and memory capacity needed for complex networks.

13 Perceptron: Invented by Frank Rosenblatt in 1957 at Cornell, the perceptron was the first artificial neural network capable of learning. The New York Times famously reported it would be “the embryo of an electronic computer that [the Navy] expects will be able to walk, talk, see, write, reproduce itself and be conscious of its existence.” While overly optimistic, this breakthrough laid the foundation for all modern neural networks.

14 Backpropagation: Published by Rumelhart, Hinton, and Williams in 1986, backpropagation solved the “credit assignment problem” (how to determine which weights in a multi-layer network were responsible for errors). This algorithm, based on the mathematical chain rule, enabled training of deep networks and directly led to the modern AI revolution. A similar algorithm was discovered by Paul Werbos in 1974 but went largely unnoticed.

The development of backpropagation algorithms in the 1980s (Rumelhart, Hinton, and Williams 1986) was a theoretical breakthrough14 and provided a systematic way to train multi-layer networks. The computational demands of this algorithm far exceeded available hardware capabilities. Training even modest networks could take weeks, making experimentation and practical applications challenging. This mismatch between algorithmic requirements and hardware capabilities contributed to a period of reduced interest in neural networks.

While we’ve established the technical foundations of deep learning in earlier sections, the term itself gained prominence in the 2010s, coinciding with significant advances in computational power and data accessibility. The field has grown exponentially, as illustrated in Figure 8. The graph reveals two remarkable trends: computational capabilities measured in floating-point operations per second (FLOPS) initially followed a \(1.4\times\) improvement pattern from 1952 to 2010, then accelerated to a 3.4-month doubling cycle from 2012 to 2022. Perhaps more striking is the emergence of large-scale models between 2015 and 2022 (not explicitly shown or easily seen in the figure), which scaled 2 to 3 orders of magnitude faster than the general trend, following an aggressive 10-month doubling cycle.

The evolutionary trends were driven by parallel advances across three dimensions: data availability, algorithmic innovations, and computing infrastructure. These three factors reinforced each other in a virtuous cycle that continues to drive progress in the field today. As Figure 9 shows, more powerful computing infrastructure enabled processing larger datasets. Larger datasets drove algorithmic innovations. Better algorithms demanded more sophisticated computing systems.

The data revolution transformed what was possible with neural networks. The rise of the internet and digital devices created unprecedented access to training data. Image sharing platforms provided millions of labeled images. Digital text collections enabled language processing at scale. Sensor networks and IoT devices generated continuous streams of real-world data. This abundance of data provided the raw material needed for neural networks to learn complex patterns effectively.

Algorithmic innovations made it possible to use this data effectively. New methods for initializing networks and controlling learning rates made training more stable. Techniques for preventing overfitting15 allowed models to generalize better to new data. Researchers discovered that neural network performance scaled predictably with model size, computation, and data quantity, leading to increasingly ambitious architectures.

15 Overfitting: When a model memorizes training examples instead of learning generalizable patterns—like a student who memorizes answers instead of understanding concepts. The model performs perfectly on training data but fails on new examples. Common signs include training accuracy continuing to improve while validation accuracy plateaus or decreases. Think of it as becoming an “expert” on a practice test who panics when facing slightly different questions on the real exam.

16 Tensor Processing Unit (TPU): Google’s custom silicon designed specifically for tensor operations, the mathematical building blocks of neural networks. First deployed internally in 2015, TPUs can perform matrix multiplications up to 30× faster than 2015-era GPUs while using less power. The name reflects their optimization for tensor operations—multi-dimensional arrays that represent data flowing through neural networks. Google has since made TPUs available through cloud services, democratizing access to this specialized AI hardware.

17 Deep Learning Frameworks: TensorFlow (Abadi et al. 2016) (released by Google in 2015) and PyTorch (Paszke et al. 2019) (released by Facebook in 2016) democratized deep learning by handling the complex mathematics automatically. Before these frameworks, implementing backpropagation required writing hundreds of lines of error-prone calculus code. Now, a complete neural network can be defined in 10-20 lines. TensorFlow emphasizes production deployment and has been downloaded over 180 million times, while PyTorch dominates research with its dynamic computation graphs. These frameworks automatically compute gradients, optimize GPU memory usage, and distribute training across multiple machines.

Computing infrastructure evolved to meet these growing demands. On the hardware side, graphics processing units (GPUs) provided the parallel processing capabilities needed for efficient neural network computation. Specialized AI accelerators like TPUs16 (Jouppi et al. 2017) pushed performance further. High-bandwidth memory systems and fast interconnects addressed data movement challenges. Equally important were software advances—frameworks and libraries17 that made it easier to build and train networks, distributed computing systems that enabled training at scale, and tools for optimizing model deployment.

The convergence of data availability, algorithmic innovation, and computational infrastructure created the foundation for modern deep learning. Building effective ML systems requires understanding the computational operations that drive infrastructure requirements. Simple mathematical operations, when scaled across millions of parameters and billions of training examples, create the massive computational demands that shaped this evolution.

Neural Network Fundamentals

Having traced neural networks’ evolution from biological inspiration through historical milestones to modern systems, we now shift focus from “why deep learning succeeded” to “how neural networks actually compute.” This section develops the mathematical and architectural foundations essential for ML systems engineering.

We take a bottom-up approach, building from simple to complex: individual neurons that perform weighted summations → layers that organize parallel computation → complete networks that transform raw inputs into predictions. Each concept introduces both mathematical principles and their systems implications. As you read, notice how each seemingly simple operation—a dot product here, an activation function there—compounds into the computational requirements we discussed earlier: millions of parameters demanding gigabytes of memory, billions of operations requiring specialized hardware, massive datasets necessitating distributed training.

The latest developments in neural architectures and emerging paradigms that build upon these foundations are explored in Chapter 20: AGI Systems. For now, we establish the foundational concepts that all neural networks share, from simple classifiers to large language models.

Network Architecture Fundamentals

The architecture of a neural network determines how information flows through the system, from input to output. While modern networks can be tremendously complex, they all build upon a few key organizational principles that directly impact system design. Understanding these principles is necessary for both implementing neural networks and appreciating why they require the computational infrastructure we’ve discussed.

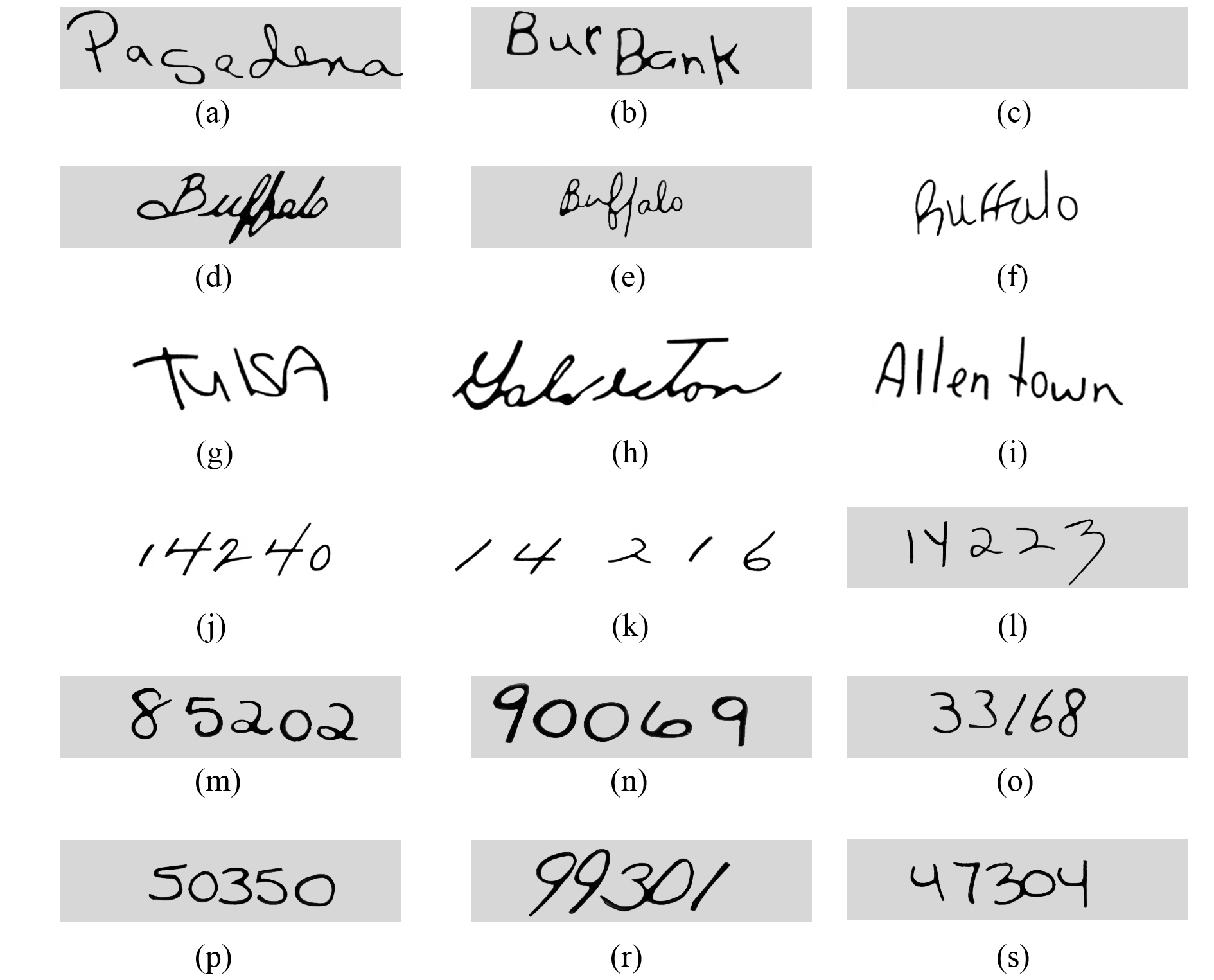

To ground these concepts in a concrete example, we’ll use handwritten digit recognition throughout this section—specifically, the task of classifying images from the MNIST dataset (Lecun et al. 1998). This seemingly simple task reveals all the fundamental principles of neural networks while providing intuition for more complex applications.

Driving practical system design, each architectural choice—from how neurons are connected to how layers are organized—creates specific computational patterns that must be efficiently mapped to hardware. This mapping between network architecture and computational requirements is crucial for building scalable ML systems.

Nonlinear Activation Functions

At the heart of all neural architectures lies a basic building block: the artificial neuron or perceptron, which implements the biological-to-artificial translation principles established earlier. From a systems perspective, understanding the perceptron’s mathematical operations is crucial because these simple operations, when replicated millions of times across a network, create the computational bottlenecks we discussed earlier.

Consider our MNIST digit recognition task. Each pixel in a 28×28 image becomes an input to our network. A single neuron in the first hidden layer might learn to detect a specific pattern—perhaps a vertical edge that appears in digits like “1” or “7.” This neuron must somehow combine all 784 pixel values into a single output that indicates whether its pattern is present.

The perceptron accomplishes this through weighted summation. It takes multiple inputs \(x_1, x_2, ..., x_n\) (in our case, \(n=784\) pixel values), each representing a feature of the object under analysis. For digit recognition, these features are simply the raw pixel intensities, though for other tasks they might be the characteristics of a home for predicting its price or the attributes of a song to forecast its popularity.

This multiplication process reveals the computational complexity beneath apparently simple operations. From a computational standpoint, each input requires storage in memory and retrieval during processing. When multiplied across millions of neurons in a deep network, these memory access patterns become a primary performance bottleneck. This is why the memory hierarchy and bandwidth considerations we discussed earlier are so critical to neural network performance.

Understanding this weighted summation process, a perceptron can be configured to perform either regression or classification tasks. For regression, the actual numerical output \(\hat{y}\) is used. For classification, the output depends on whether \(\hat{y}\) crosses a certain threshold. If \(\hat{y}\) exceeds this threshold, the perceptron might output one class (e.g., ‘yes’), and if it does not, another class (e.g., ‘no’).

Visualizing these mathematical concepts, Figure 10 illustrates the core building blocks of a perceptron, which serves as the foundation for more complex neural networks. Scaling beyond individual units, layers of perceptrons work in concert, with each layer’s output serving as the input for the subsequent layer. This hierarchical arrangement creates deep learning models capable of tackling increasingly sophisticated tasks, from image recognition to natural language processing.

Breaking down the computational mechanics, each input \(x_i\) has a corresponding weight \(w_{ij}\), and the perceptron simply multiplies each input by its matching weight. The intermediate output, \(z\), is computed as the weighted sum of inputs: \[ z = \sum (x_i \cdot w_{ij}) \]

The apparent simplicity of this mathematical expression masks its computational complexity. When scaled across millions of neurons and billions of parameters, these memory access patterns become the dominant performance bottleneck in neural network computation.

Enhancing the model’s flexibility, to this intermediate calculation, a bias term \(b\) is added, allowing the model to better fit the data by shifting the linear output function up or down. Thus, the intermediate linear combination computed by the perceptron including the bias becomes: \[ z = \sum (x_i \cdot w_{ij}) + b \]

This mathematical formulation directly drives the hardware requirements we discussed earlier. The summation requires accumulator units, the multiplications demand high-throughput arithmetic units, and the memory accesses necessitate high-bandwidth memory systems. Understanding this connection between mathematical operations and hardware requirements is crucial for designing efficient ML systems.

Beyond linear transformations, activation functions are critical nonlinear transformations that enable neural networks to learn complex patterns by converting linear weighted sums into nonlinear outputs. Without activation functions, multiple linear layers would collapse into a single linear transformation, severely limiting the network’s expressive power. Figure 11 illustrates the four most commonly used activation functions and their characteristic shapes.

The choice of activation function profoundly impacts both learning effectiveness and computational efficiency. Understanding the mathematical properties of each function is essential for designing effective neural networks. The most commonly used activation functions include:

Sigmoid

The sigmoid function maps any input value to a bounded range between 0 and 1: \[ \sigma(x) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-x}} \]

This S-shaped curve (visible in Figure 11, top-left) produces outputs that can be interpreted as probabilities, making sigmoid particularly useful for binary classification tasks. For very large positive inputs, the function approaches 1; for very large negative inputs, it approaches 0. The smooth, continuous nature of sigmoid makes it differentiable everywhere, which is necessary for gradient-based learning.

However, sigmoid has a significant limitation: for inputs with large absolute values (far from zero), the gradient becomes extremely small—a phenomenon called the vanishing gradient problem18. During backpropagation, these small gradients are multiplied together across layers, causing gradients in early layers to become exponentially tiny. This effectively prevents learning in deep networks, as weight updates become negligible.

18 Vanishing Gradients: When gradients become exponentially small as they propagate backward through many layers, learning effectively stops in early layers. This occurs because gradients are computed via the chain rule, multiplying derivatives from each layer. If these derivatives are consistently less than 1 (as with saturated sigmoid outputs), their product shrinks exponentially with network depth. This problem is addressed in detail in Chapter 8: AI Training.

Sigmoid outputs are not zero-centered (all outputs are positive). This asymmetry can cause inefficient weight updates during optimization, as gradients for weights connected to sigmoid units will all have the same sign.

Tanh

The hyperbolic tangent function addresses sigmoid’s zero-centering limitation by mapping inputs to the range \((-1, 1)\): \[ \tanh(x) = \frac{e^x - e^{-x}}{e^x + e^{-x}} \]

As shown in Figure 11 (top-right), tanh produces an S-shaped curve similar to sigmoid but centered at zero. Negative inputs map to negative outputs, while positive inputs map to positive outputs. This symmetry helps balance gradient flow during training, often leading to faster convergence than sigmoid.

Like sigmoid, tanh is smooth and differentiable everywhere. It still suffers from the vanishing gradient problem for inputs with large magnitudes. When the function saturates (approaches -1 or 1), gradients become very small. Despite this limitation, tanh’s zero-centered outputs make it preferable to sigmoid for hidden layers in many architectures, particularly in recurrent neural networks where maintaining balanced activations across time steps is important.

ReLU

The Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) revolutionized deep learning by providing a simple solution to the vanishing gradient problem (Nair and Hinton 2010)19: \[ \text{ReLU}(x) = \max(0, x) = \begin{cases} x & \text{if } x > 0 \\ 0 & \text{if } x \leq 0 \end{cases} \]

19 ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit): A piecewise linear activation function that outputs the input directly if positive, otherwise outputs zero. Introduced by Nair and Hinton in 2010, ReLU solved the vanishing gradient problem and became the default activation function in modern deep learning due to its computational simplicity and biological inspiration from neuron firing patterns.

Figure 11 (bottom-left) shows ReLU’s characteristic shape: a straight line for positive inputs and zero for negative inputs. This simplicity provides several advantages:

Gradient Flow: For positive inputs, ReLU’s gradient is exactly 1, allowing gradients to flow unchanged through the network. This prevents the vanishing gradient problem that plagues sigmoid and tanh in deep architectures.

Sparsity: By setting all negative activations to zero, ReLU introduces natural sparsity in the network. Typically, about 50% of neurons in a ReLU network output zero for any given input. This sparsity can help reduce overfitting and makes the network more interpretable.

Computational Efficiency: Unlike sigmoid and tanh, which require expensive exponential calculations, ReLU is computed with a simple comparison and conditional operation: output = (input > 0) ? input : 0. This simplicity translates to faster computation and lower energy consumption, particularly important for deployment on resource-constrained devices.

ReLU is not without drawbacks. The dying ReLU problem occurs when neurons become “stuck” outputting zero. If a neuron’s weights are updated such that its weighted input is consistently negative, the neuron outputs zero and contributes zero gradient during backpropagation. This neuron effectively becomes non-functional and can never recover. Careful initialization and learning rate selection help mitigate this issue.

Softmax

Unlike the previous activation functions that operate independently on each value, softmax considers all values simultaneously to produce a probability distribution: \[ \text{softmax}(z_i) = \frac{e^{z_i}}{\sum_{j=1}^K e^{z_j}} \]

For a vector of \(K\) values (often called logits), softmax transforms them into \(K\) probabilities that sum to 1. Figure 11 (bottom-right) shows one component of the softmax output; in practice, softmax processes entire vectors where each element’s output depends on all input values.

Softmax is almost exclusively used in the output layer for multi-class classification problems. By converting arbitrary real-valued logits into probabilities, softmax enables the network to express confidence across multiple classes. The class with the highest probability becomes the predicted class. The exponential function ensures that larger logits receive disproportionately higher probabilities, creating clear distinctions between classes when the network is confident.

The mathematical relationship between input logits and output probabilities is differentiable, allowing gradients to flow back through softmax during training. When combined with cross-entropy loss (discussed in Chapter 8: AI Training), softmax produces particularly clean gradient expressions that guide learning effectively.

Why ReLU Dominates in Practice: Beyond its mathematical benefits like avoiding vanishing gradients, ReLU’s hardware efficiency explains its widespread adoption. Computing \(\max(0,x)\) requires a single comparison operation, while sigmoid and tanh require computing exponentials—operations that are orders of magnitude more expensive in both time and energy. This computational simplicity means ReLU can be executed faster on any processor and consumes significantly less power, a critical consideration for battery-powered devices. The computational and hardware implications of activation functions, including performance benchmarks and implementation strategies for modern accelerators, are explored in Chapter 8: AI Training.

As detailed in the activation function section above, these nonlinear transformations convert the linear input sum into a non-linear output: \[ \hat{y} = \sigma(z) \]

Thus, the final output of the perceptron, including the activation function, can be expressed as:

Figure 12 shows an example where data exhibit a nonlinear pattern that could not be adequately modeled with a linear approach, demonstrating why the nonlinear activation functions discussed earlier are essential for complex pattern recognition.

The universal approximation theorem20 establishes that neural networks with activation functions can approximate arbitrary functions. This theoretical foundation, combined with the computational and optimization characteristics of specific activation functions like ReLU and sigmoid discussed above, explains neural networks’ practical effectiveness in complex tasks.

20 Universal Approximation Theorem: Proven by George Cybenko (1989) and Kurt Hornik (1991), this theorem states that neural networks with just one hidden layer containing enough neurons can approximate any continuous function to arbitrary accuracy. However, the theorem doesn’t specify how many neurons are needed (could be exponentially many) or how to find the right weights. This explains why neural networks are theoretically powerful but doesn’t guarantee practical learnability—a key distinction that drove the development of deep learning architectures and better training algorithms.

Combining the linear combination with the activation function, the complete perceptron computation is: \[ \hat{y} = \sigma\left(\sum (x_i \cdot w_{ij}) + b\right) \]

Layers and Connections

While a single perceptron can model simple decisions, the power of neural networks comes from combining multiple neurons into layers. A layer is a collection of neurons that process information in parallel. Each neuron in a layer operates independently on the same input but with its own set of weights and bias, allowing the layer to learn different features or patterns from the same input data.

In a typical neural network, we organize these layers hierarchically:

- Input Layer: Receives the raw data features

- Hidden Layers: Process and transform the data through multiple stages

- Output Layer: Produces the final prediction or decision

Figure 13 illustrates this layered architecture. When data flows through these layers, each successive layer transforms the representation of the data, gradually building more complex and abstract features. This hierarchical processing is what gives deep neural networks their remarkable ability to learn complex patterns.

Data Flow Through Network Layers

As data flows through the network, it is transformed at each layer to extract meaningful patterns. The weighted summation and activation process we established for individual neurons scales up: each layer applies these operations in parallel across all its neurons, with outputs from one layer becoming inputs to the next. This creates a hierarchical pipeline where simple features detected in early layers combine into increasingly complex patterns in deeper layers—enabling neural networks to learn sophisticated representations from raw data.

Parameters and Connections

The learnable parameters of neural networks consist primarily of weights and biases, which together determine how information flows through the network and how transformations are applied to input data. This section examines how these parameters are organized and structured within neural networks. We explore weight matrices that connect layers, connection patterns that define network topology, bias terms that provide flexibility in transformations, and parameter organization strategies that enable efficient computation.

Weight Matrices

Weights determine how strongly inputs influence neuron outputs. In larger networks, these organize into matrices for efficient computation across layers. For example, in a layer with \(n\) input features and \(m\) neurons, the weights form a matrix \(\mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times m}\). Each column in this matrix represents the weights for a single neuron in the layer. This organization allows the network to process multiple inputs simultaneously, an essential feature for handling real-world data efficiently.

Recall that for a single neuron, we computed \(z = \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i \cdot w_{ij}) + b\). When we have a layer of \(m\) neurons, we could compute each neuron’s output separately, but matrix operations provide a much more efficient approach. Rather than computing each neuron individually, matrix multiplication enables us to compute all \(m\) outputs simultaneously: \[ \mathbf{z} = \mathbf{x}^T\mathbf{W} + \mathbf{b} \]

This matrix organization is more than just mathematical convenience; it reflects how modern neural networks are implemented for efficiency. Each weight \(w_{ij}\) represents the strength of the connection between input feature \(i\) and neuron \(j\) in the layer.

Network Connectivity Architectures

In the simplest and most common case, each neuron in a layer is connected to every neuron in the previous layer, forming what we call a “dense” or “fully-connected” layer. This pattern means that each neuron has the opportunity to learn from all available features from the previous layer. While this chapter focuses on fully-connected layers to establish foundational principles, alternative connectivity patterns (explored in Chapter 4: DNN Architectures) can dramatically improve efficiency for structured data by restricting connections based on problem characteristics.

Figure 14 illustrates these dense connections between layers. For a network with layers of sizes \((n_1, n_2, n_3)\), the weight matrices would have dimensions:

- Between first and second layer: \(\mathbf{W}^{(1)} \in \mathbb{R}^{n_1 \times n_2}\)

- Between second and third layer: \(\mathbf{W}^{(2)} \in \mathbb{R}^{n_2 \times n_3}\)

Bias Terms

Each neuron in a layer also has an associated bias term. While weights determine the relative importance of inputs, biases allow neurons to shift their activation functions. This shifting is crucial for learning, as it gives the network flexibility to fit more complex patterns.

For a layer with \(m\) neurons, the bias terms form a vector \(\mathbf{b} \in \mathbb{R}^m\). When we compute the layer’s output, this bias vector is added to the weighted sum of inputs: \[ \mathbf{z} = \mathbf{x}^T\mathbf{W} + \mathbf{b} \]

The bias terms21 effectively allow each neuron to have a different “threshold” for activation, making the network more expressive.

21 Bias Terms: Constant values added to weighted inputs that allow neurons to shift their activation functions horizontally, enabling networks to model patterns that don’t pass through the origin. Without bias terms, a neuron with all-zero inputs would always produce zero output, severely limiting representational capacity. Biases typically require 1-5% of total parameters but provide crucial flexibility—for example, allowing a digit classifier to have different baseline tendencies for recognizing each digit based on frequency in training data.

Weight and Bias Storage Organization

The organization of weights and biases across a neural network follows a systematic pattern. For a network with \(L\) layers, we maintain:

A weight matrix \(\mathbf{W}^{(l)}\) for each layer \(l\)

A bias vector \(\mathbf{b}^{(l)}\) for each layer \(l\)

Activation functions \(f^{(l)}\) for each layer \(l\)

This gives us the complete layer computation: \[ \mathbf{h}^{(l)} = f^{(l)}(\mathbf{z}^{(l)}) = f^{(l)}(\mathbf{h}^{(l-1)T}\mathbf{W}^{(l)} + \mathbf{b}^{(l)}) \] Where \(\mathbf{h}^{(l)}\) represents the layer’s output after applying the activation function.

Before proceeding to network topology and training, verify your understanding of the foundational concepts we’ve covered:

Core Concepts:

Systems Implications:

Self-Test Example: For a digit recognition network with layers 784→100→10, calculate: (1) parameters in each weight matrix, (2) total parameter count, (3) activations stored during inference for a single image.

If any of these feel unclear, review Section 1.4 (Neural Network Fundamentals), Section 1.4.1.1 (Neurons and Activations), or Section 1.4.2 (Weights and Biases) before continuing. The upcoming sections on training and optimization build directly on these foundations.

Architecture Design

Network topology describes how individual neurons organize into layers and connect to form complete neural networks. Building intuition begins with a simple problem that became famous in AI history22.