Week 6: Can AI Co-Design Distributed Systems? Scaling from 1 GPU to 1,000

Let’s imagine the following (quite realistic) scenario: You’ve learned how AI can optimize CPU code. You’ve seen AI generate blazingly fast GPU kernels. Your single machine performance is perfect. Now you need to scale to 1,000 GPUs to train your frontier model. Or maybe 200,000 GPUs, like xAI’s Colossus supercomputer, currently the world’s largest AI training cluster. What new problems arise, and how can we leverage AI to solve them?

The network becomes your bottleneck.

That thing you took for granted when optimizing individual machines with AI? It’s now the critical constraint. Here’s what makes distributed systems fundamentally different from everything we’ve explored so far. Unlike code that either works or doesn’t, unlike benchmarks that give you deterministic speedup numbers, distributed systems exist in a world of continuous adaptation, unpredictable failures, and dynamic conditions that change moment by moment.

Suddenly, everything you learned about AI for system design in the past five weeks isn’t enough. This week, we confront the messy reality where “does it work?” has no single answer.

PHASE 1: The Fundamental Shift

The Journey to Week 6: From Determinism to Dynamism

Over the past five weeks, we’ve been building toward this moment. In Week 3, we explored code generation, where success means “does it compile and pass tests?” In Week 4, we tackled CPU performance optimization with ECO, where you could measure speedups deterministically. In Week 5, we dove into GPU kernel optimization, where KernelBench and Kevin showed us that iterative refinement could produce measurable performance gains.

All of these challenges shared a crucial characteristic. They had clear verification criteria. Write code, run tests, measure performance. The environment was controlled, the hardware was predictable, and optimization was largely deterministic.

But distributed systems shatter this comfortable predictability.

The Network Is Not Forgiving

When you optimize code on a single machine, the hardware provides remarkably consistent behavior. Your CPU’s cache hierarchy doesn’t randomly change. Your GPU’s memory bandwidth is stable. Run the same kernel twice, you get essentially the same performance (modulo thermal effects and background processes).

Distributed systems operate under fundamentally different rules:

Network conditions fluctuate constantly. That 100 Gbps link between two nodes? It’s shared with other traffic. Congestion can cut effective bandwidth by orders of magnitude, and it changes minute by minute.

Workload patterns shift unpredictably. The traffic patterns that worked perfectly yesterday might cause cascading failures today when a different mix of jobs hits the cluster.

Failures are not anomalies. They’re the norm. With thousands of machines, something is always failing. A switch goes down, a cable gets loose, a NIC overheats. Your system must handle these gracefully, continuously.

Temporal dynamics matter. Time of day effects, batch job submissions, geographical traffic patterns. Distributed systems exist in time in ways that single machine optimization doesn’t capture.

This was a central theme in our class discussion with guest speaker Martin Maas from Google DeepMind. Martin Maas is a Staff Research Scientist at Google DeepMind who has spent his career at the intersection of ML and systems. His work focuses on practical deployments of ML driven optimization at warehouse scale. His experience deploying learned systems at Google gives him unique insight into what actually works in production versus what looks good in research papers. Unlike the clean world of GPU kernel benchmarks, distributed systems require continuous adaptation to dynamic conditions. You can’t just “test” your way to correctness when the environment itself is constantly changing.

Martin Maas is a Staff Research Scientist at Google DeepMind who has spent his career at the intersection of ML and systems. His work focuses on practical deployments of ML driven optimization at warehouse scale. His experience deploying learned systems at Google gives him unique insight into what actually works in production versus what looks good in research papers. Unlike the clean world of GPU kernel benchmarks, distributed systems require continuous adaptation to dynamic conditions. You can’t just “test” your way to correctness when the environment itself is constantly changing.

From Compute-Bound to Communication-Bound

Why does the network become so unpredictable? And why does scaling to thousands of GPUs fundamentally change the optimization problem? To understand this, we need to examine what happens when you move from single machine to distributed training.

The Communication Explosion

Consider training a large language model. On a single GPU, your bottleneck might be memory bandwidth or compute throughput. But when you distribute training across 1,000 GPUs, something dramatic happens. The communication overhead begins to dominate everything else.

At the scale of modern AI infrastructure, the network bandwidth required is staggering. These systems can generate petabytes of gradient data per day that must be synchronized across the cluster. A single slow network link, a suboptimal collective communication algorithm, or poor workload placement can bottleneck the entire training run.

To understand why, we need to examine how distributed training actually works. When training is distributed, the model’s computations are divided across many devices, but these devices must constantly exchange information to stay synchronized. This creates communication patterns fundamentally different from the point-to-point messages we’re familiar with in traditional networked applications.

Collective Communication Patterns become the dominant paradigm. Unlike simple point-to-point messages, distributed training relies on collective operations where all nodes must coordinate simultaneously:

-

All-Reduce: Every node contributes data, and all nodes receive the aggregated result. Here’s why this matters. When training a neural network across 1,000 GPUs, each GPU computes gradients for its batch of data. But to update the model correctly, every GPU needs the average gradient across all batches. All-reduce performs this averaging and distributes the result back to all nodes. This fundamental operation happens thousands of times during training.

-

All-Gather: Each node broadcasts its data to all other nodes. Essential when different nodes hold different parts of the model (model parallelism), and each node needs to see the complete set of parameters or activations.

-

Broadcast: One node sends data to all others. Used for distributing updated model parameters from a central coordinator to all workers.

The efficiency of these operations depends critically on the network topology and the algorithms used to implement them.

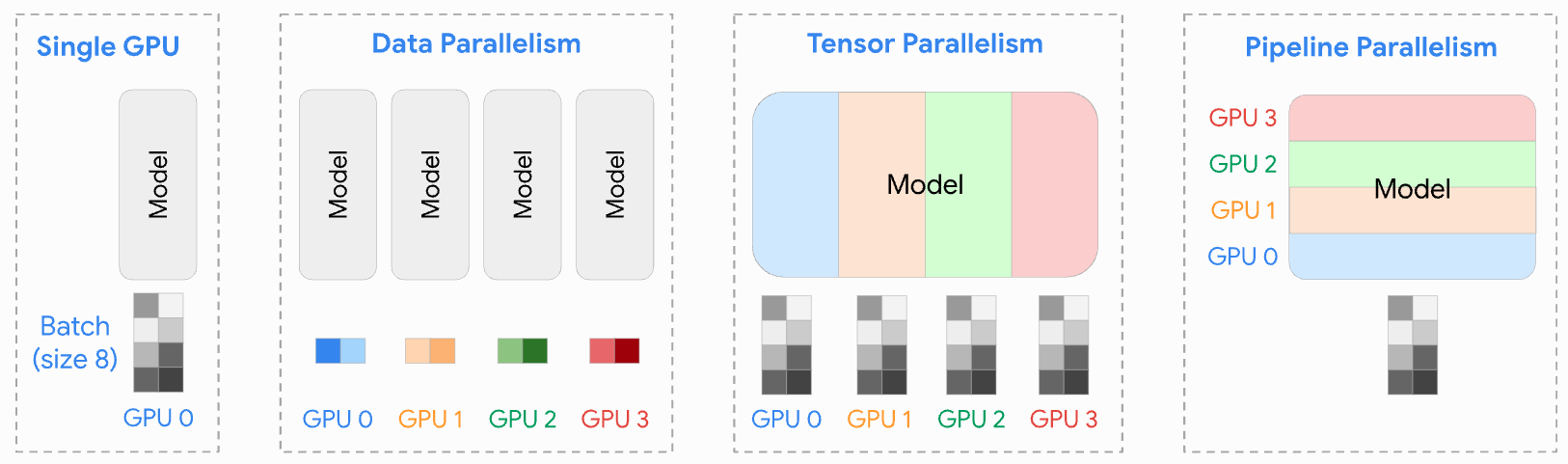

Multiple Parallelism Strategies: Our class discussion revealed that modern distributed training employs several forms of parallelism simultaneously.

Data Parallelism: Each node processes different data batches with identical model replicas. Requires all-reduce to synchronize gradients.

Tensor Parallelism: Split individual layers across multiple devices. Creates fine-grained communication dependencies.

Expert Parallelism: In mixture of experts models, different nodes specialize in different expert networks, requiring dynamic routing of activations.

Pipeline Parallelism: Split the model into stages across devices, creating a pipeline of computation with inter-stage communication.

Each parallelism strategy creates different communication patterns, and the optimal choice depends on model architecture, cluster topology, and workload characteristics.

The Topology Challenge

Visualizing the Network Topology: Imagine diagrams showing ring, tree, and fat-tree topologies with communication patterns overlaid. The ring topology has uniform bandwidth but high latency for large rings. Tree topology creates natural aggregation points but risks bottlenecks. Fat-tree provides multiple paths but requires intelligent routing to utilize them effectively.

Network topology (how your machines are physically connected) becomes critically important at scale. This isn’t just an academic concern. It’s a fundamental constraint that determines what’s possible.

Ring Topology: Arranging nodes in a ring enables efficient all-reduce through a ring-reduce-scatter followed by ring-all-gather. This minimizes the data volume each link must carry, but latency grows linearly with the number of nodes.

Tree Topology: Hierarchical aggregation can reduce latency, but creates potential bottlenecks at higher levels of the tree. Load imbalance can cause some links to saturate while others sit idle.

Fat-Tree and Clos Networks: Modern data centers often use fat-tree architectures with multiple paths between nodes, providing both high bandwidth and fault tolerance. But exploiting this effectively requires sophisticated routing algorithms.

The critical insight from our class discussion is this. You cannot separate algorithm design from network topology. The optimal parallelization strategy depends on your network, and the optimal network design depends on your workload.

This interdependence creates the core challenge. How do you design a network when you don’t know what workload patterns will emerge? How do you choose a parallelization strategy when you don’t know how the network will handle it? Traditional approaches solve these problems separately and hope the pieces fit together reasonably well.

They don’t. And that’s where co-design becomes necessary.

PHASE 2: Co-Design as the Answer

The COSMIC Approach

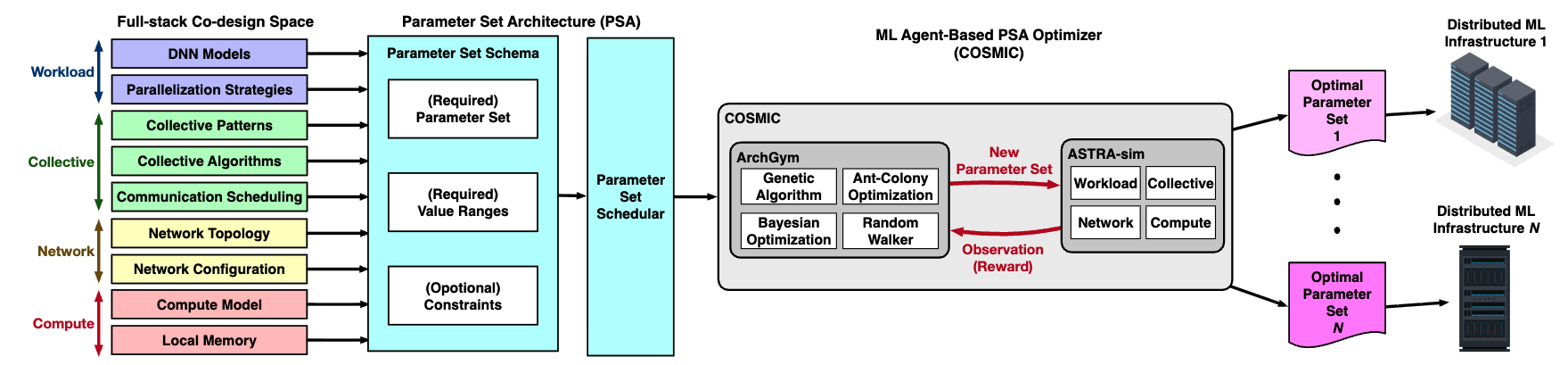

What if, instead of designing each layer independently, we optimized them together? This brings us to one of our main papers this week: “COSMIC: Enabling Full-Stack Co-Design and Optimization of Distributed Machine Learning Systems”. COSMIC addresses the chicken-and-egg problem head on by treating workload and network as a single optimization problem.

The Traditional Approach (and Why It Fails)

Traditionally, we’ve treated workload and infrastructure as separate concerns:

- Hardware teams design networks based on general assumptions about traffic patterns

- ML engineers develop training strategies assuming the network is a fixed resource

- Systems engineers try to optimize the scheduling and placement of jobs on existing infrastructure

This separation creates a fundamental inefficiency. Imagine you’re training a massive transformer model. You choose pipeline parallelism because it fits your model size. Your network is a standard fat-tree topology because that’s what the data center provides. Each decision, taken independently, seems reasonable.

But here’s what traditional optimization misses. Pipeline parallelism creates specific communication patterns that might perform poorly on fat tree networks. Meanwhile, a different parallelism strategy might actually run faster on the existing network. Or, if you’re designing a new cluster, you could build a network optimized for your specific workload’s communication patterns.

Traditional approaches can’t discover these cross-layer optimizations because they optimize each component in isolation.

COSMIC’s Co-Design Philosophy

COSMIC takes a radically different approach. Jointly optimize workload mapping and network topology together.

The system explores questions like these. Should we use more data parallelism or more model parallelism for this specific model architecture? What network topology best supports the communication patterns this choice creates? Can we modify the network design to eliminate bottlenecks we observe in the workload? Should we adjust our parallelization strategy to better match network constraints?

The paper demonstrates that this co-design approach yields significant improvements in both efficiency and cost. By considering workload and network together, COSMIC discovers optimization opportunities that neither hardware-centric nor software-centric approaches can find.

This is full-stack optimization in its truest form. Breaking down the artificial boundaries between layers that we created for human comprehension but that limit system performance.

When Does Co-Design Actually Make Sense?

But here’s the pragmatic question we must ask. Does co-design actually make sense for your workload?

Co-design is expensive. It requires reasoning about workload characteristics, network topology, and hardware constraints simultaneously. You’re not just optimizing one layer. You’re redesigning multiple layers together. That level of effort demands justification.

The answer depends on scale. If you’re running ChatGPT or training frontier language models at mega-scale, where you’re distributing work across thousands of GPUs continuously, then yes, co-design absolutely makes sense.

Consider the real-world scale. OpenAI’s infrastructure for GPT-4 training reportedly involved around 25,000 GPUs. Microsoft and OpenAI built supercomputers with tens of thousands of GPUs interconnected with InfiniBand networks. At this scale, even a 10% improvement in communication efficiency translates to massive cost savings. The efficiency improvements COSMIC demonstrates (reduced training time, lower network costs, better resource utilization) directly translate to millions of dollars saved and competitive advantages in model deployment.

But if you’re training smaller models occasionally, or running distributed workloads at more modest scales? The engineering effort to co-design your system might not be worth it. Standard network topologies and conventional parallelism strategies might be good enough.

This is a crucial consideration as AI for systems matures. Not every optimization technique applies at every scale. The question isn’t just “can AI co-design distributed systems?” but “when should it?”

PHASE 3: AI as Co-Pilot for Co-Design Path

Why AI Becomes Necessary

COSMIC demonstrates what co-design can achieve. Jointly optimizing workload mapping and network topology unlocks performance gains that siloed optimization misses. But here’s the practical challenge. How do you actually implement this co-design?

The search space is enormous. Thousands of potential parallelization strategies, dozens of network topology options, continuous tradeoffs between latency, bandwidth, and cost. Traditional optimization techniques (exhaustive search, hand crafted heuristics) simply can’t navigate this space effectively.

This is precisely where AI driven optimization becomes not just useful, but necessary. The unpredictable, dynamic nature of distributed systems, combined with vast design spaces, makes them a natural domain for machine learning. Unlike static compiler optimizations or one time kernel tuning, distributed systems require continuous adaptation. This is exactly what AI systems excel at.

Learning from Dynamic Systems: The Cooling Example

To understand how AI tackles distributed system optimization, let’s start with a canonical example outside the networking domain: Google’s data center cooling system. This example illustrates the pattern we’ll see repeated in network optimization.

Data center cooling presents a challenge remarkably similar to distributed system optimization:

- Dynamic conditions: Weather changes, workload varies, equipment ages

- Complex interactions: Thousands of sensors, interdependent cooling systems

- Continuous operation: Can’t stop to “test” solutions offline

- Safety-critical: Must never let equipment overheat

DeepMind’s approach using reinforcement learning achieved a 40% reduction in cooling energy. Not through one time optimization, but through continuous adaptation to changing conditions. The system learns policies that respond to the current state of the data center, adjusting cooling in real time as conditions evolve.

The key insight is simple. AI doesn’t need perfect models of system behavior. It learns from experience, adapts to distribution shifts, and handles the probabilistic nature of real world systems in ways that hand crafted heuristics never could.

Reinforcement Learning for Congestion Control

Our second main paper, “Reinforcement Learning for Datacenter Congestion Control”, applies similar principles to network optimization. This builds on a rich history of learned network protocols, including pioneering work like Remy from MIT, which first demonstrated that computer generated congestion control could outperform human designed algorithms.

Traditional congestion control algorithms like TCP use hand designed rules. Multiplicative decrease on packet loss, additive increase otherwise. These rules were carefully crafted by networking experts over decades, but they’re fundamentally reactive and assume relatively stable conditions.

The paper demonstrates that learned policies can outperform traditional algorithms in three ways:

Adapting to traffic patterns. Different flows have different characteristics, and learned policies can recognize and respond appropriately.

Anticipating congestion. Rather than reacting to packet loss, learned policies can predict congestion before it becomes severe.

Handling multiple objectives. Balancing throughput, latency, and fairness in ways that hand crafted rules struggle with.

This sounds promising. AI can learn cooling policies. AI can optimize congestion control. We have the techniques. We understand the principles.

But here’s where the gap between research and production becomes stark.

The Deployment Reality Check

Deploying these learned systems at scale is hard. Much harder than the research papers suggest. This was a key insight that emerged from our class discussion. Most existing systems were never designed to integrate machine learning. They were built for hand coded heuristics, and retrofitting ML into them is a fundamental architectural challenge.

Consider the Linux kernel as a concrete example. The kernel makes thousands of scheduling, memory management, and I/O decisions. In principle, many of these could be improved with learned policies. But in practice, the kernel doesn’t have clean separation between:

- Mechanisms: The low-level operations the system can perform

- Policies: The decisions about when to perform them

Here’s what this means in practice. Imagine you want to use ML to improve CPU scheduling. In an ideally designed system, you’d have a clean interface where you could swap in your learned scheduler while keeping all the low level mechanisms unchanged. But in the Linux kernel, scheduling logic is intertwined with priority handling, load balancing, interrupt handling, and numerous other subsystems. To add ML based scheduling, you’d need to refactor thousands of lines of carefully tuned code. A risky proposition in production systems.

This intertwining makes it nearly impossible to “drop in” a learned policy without rewriting large portions of the kernel. The class discussion highlighted that we need to refactor systems from first principles to support ML integration, not try to retrofit ML into systems designed for hand coded heuristics.

What would that actually require?

Design patterns for ML integration: Shared interfaces and abstractions that make it easy to replace hand-coded policies with learned ones

Separate inference stacks: Online learning (where models run in the critical path) has very different requirements than offline learning (where models optimize configurations before deployment)

Monitoring and safety infrastructure: Systems to detect when learned policies misbehave and fall back to safe defaults

Simulation capabilities: Ways to test learned policies under diverse conditions before deploying them to production

The lack of this infrastructure is why, as noted in our discussion, we see “iconic demos from Google and Meta and so forth, and then you won’t hear anything from anybody else.” Most organizations simply don’t have the infrastructure to deploy ML driven system optimization safely.

This infrastructure gap makes the practical deployment of learned systems orders of magnitude harder than developing the ML models themselves.

The Scaling Laws Paradox

Which leads us to a surprising observation. An unexpected theme emerged in our class discussion. As model scaling shows diminishing returns (with models like GPT 4.5 plateauing), distributed systems optimization paradoxically becomes more critical, not less. The economics of AI are shifting.

When scaling was the answer to everything, suboptimal distributed training was wasteful but acceptable. Throw more hardware at the problem. But building and operating these massive clusters is expensive. Meta’s Research SuperCluster cost hundreds of millions to build. Power consumption for large GPU clusters can exceed 20 MW.The Energy Elephant in the Room: We’re not deeply addressing it in this post, but the energy implications are staggering. OpenAI’s partnership with AMD will deploy 6 gigawatts of GPU infrastructure, with 1 gigawatt arriving in 2026 alone. To put this in perspective, a typical nuclear power plant produces around 1 gigawatt. This makes efficiency optimization not just an economic imperative but an environmental one. Every percentage point of improvement in communication efficiency translates directly to reduced power consumption at planetary scale. Now, how you use your GPUs determines whether you can afford to train competitive models at all. The efficiency of communication patterns, the intelligence of workload distribution, the optimization of network topology. These become competitive advantages, not just nice-to-haves.

The class discussion highlighted this shift. The focus moves toward quality improvements. Better data curation, algorithmic innovations, and system optimization. Each of these directions demands distributed systems that can adapt and efficiently utilize resources. Exactly what papers like COSMIC enable.

The irony is beautiful. Just as “just scale it” stops working, the techniques to make scaling efficient become essential. Co-design and AI driven optimization aren’t just academic exercises. They’re the difference between profitable and unprofitable AI deployment.

PHASE 4: The Research Frontier

The Benchmark Challenge

One of the most thought provoking parts of our class discussion centered on benchmarks. This connects directly to the fundamental challenge of dynamic systems.

Traditional systems benchmarks assume relatively stable conditions. Run the workload, measure the results, compare systems. But distributed systems are fundamentally dynamic. A system that performs well on a static benchmark might fail catastrophically when workload patterns shift unexpectedly. Which happens constantly in production.

The class explored the need for dynamic benchmarks that:

- Capture realistic workload variations over time

- Include distribution shifts and unexpected events

- Test system adaptability, not just peak performance

- Reflect the long tail of unusual conditions that matter in production

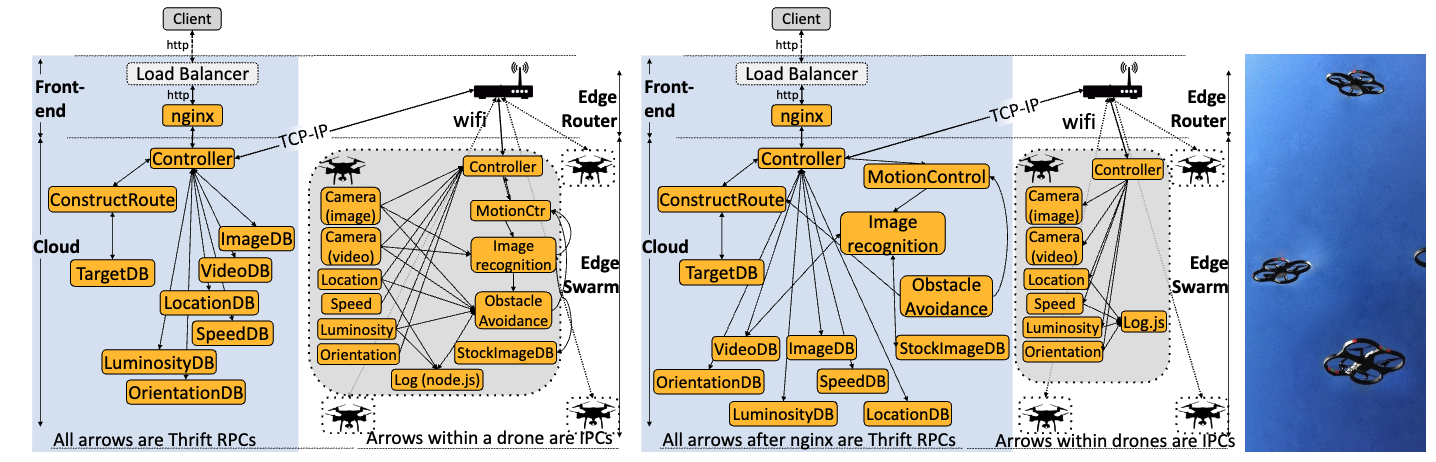

We discussed the DeathStarBench suite as an example of benchmarks designed to elicit complex system behaviors. These benchmarks model real-world microservices with realistic request patterns, dependencies, and failure modes.

This connects back to our Week 3 discussion of SWE-Bench and the challenge of benchmark overfitting. Just as AI systems can excel at competitive programming while struggling with real software engineering, they can optimize for static distributed system benchmarks while failing in dynamic production environments.

The challenge for the research community is clear. How do we create benchmarks that capture dynamism without making them so complex that results become irreproducible?

The Self-Improvement Vision

Toward the end of our discussion, students asked about self improving ML systems. Can we create “automatic positive feedback loops” where systems learn to optimize themselves?

The class was optimistic about this direction, particularly in distributed systems where:

- Production systems generate massive amounts of telemetry

- Latency, throughput, and cost are measurable and meaningful

- Simulation and staged rollouts let you test improvements before production

Projects like Google’s AlphaEvolve (discovering improved sorting algorithms) and MIT’s Decima (learning scheduling algorithms for data processing clusters) exemplify this self improvement paradigm. These systems don’t just optimize parameters. They generate entirely new strategies that outperform human designed alternatives.

For distributed systems, self improvement could mean:

- Learning better collective communication algorithms for specific network topologies

- Discovering novel scheduling strategies (as Decima did for Spark clusters)

- Automatically adapting to new hardware as it’s deployed

However, the discussion highlighted that generalizability remains a challenge. A policy learned for one cluster configuration might not transfer to others. Creating systems that learn broadly applicable insights (not just workload specific hacks) is an important open research problem.

The Academic Opportunity

Throughout our discussion, a critical distinction emerged. Industry must work with existing systems, retrofitting ML where possible. Academia can explore designing systems from first principles with ML integration in mind.

This is a unique opportunity for academic research. Rather than asking “how do we add ML to Linux?”, we can ask “if we designed an OS today knowing ML would be central, what would it look like?”

Some provocative questions for the academic community:

System Interfaces: What abstractions make it easy to replace hand coded policies with learned ones? How do we design APIs that naturally accommodate learning?

Formal Guarantees: Can we provide formal safety guarantees for systems with learned components? How do we bound worst case behavior while allowing ML to optimize the common case?

Transfer Learning: How do we train policies that generalize across different hardware configurations, workload patterns, and deployment scenarios?

Interpretability: When a learned policy makes a decision, can we explain why? This matters for debugging, trust, and extracting insights for future system design.

Dynamic Benchmarks: What benchmarks would properly evaluate AI driven distributed systems? How do we avoid overfitting while ensuring reproducibility?

These are questions that academic research is uniquely positioned to explore, unconstrained by the need to maintain compatibility with decades of existing infrastructure.

Synthesis: The Architecture 2.0 Connection

Week 6 marks the culmination of Phase 1, but it also reveals why the Architecture 2.0 vision from Week 1 is necessary. Let’s connect the threads.

Breaking Down Artificial Boundaries

COSMIC demonstrates a principle central to Architecture 2.0. Optimal design requires reasoning across traditional abstraction layers. We created these layers (application, system software, network, hardware) to manage complexity for human designers. But they’re artificial constraints that limit optimization potential.

The progression across Phase 1 reveals this truth:

- Week 3 and 4 optimized within the software layer

- Week 5 crossed the software-hardware boundary (GPU kernels)

- Week 6 crosses the software-network boundary (distributed systems)

Each week, we’ve pushed against these artificial boundaries. COSMIC’s co-design of workload and network topology is full stack optimization. Exactly the kind of cross-layer reasoning that Architecture 2.0 envisions.

This connects to Leiserson’s “room at the top” vision. Enormous performance gaps exist between current systems and what’s theoretically possible. Distributed systems exemplify this gap. Most clusters operate far below their theoretical efficiency because we optimize each layer independently.

The Data Challenge Redux

This also connects to the data and benchmark challenge from Week 2. How do we create datasets and benchmarks for distributed system optimization?

Unlike code generation (where we have GitHub) or architecture exploration (where we have simulators), distributed systems present unique challenges:

- Dynamic behavior: Static benchmarks don’t capture the continuous adaptation required

- Scale requirements: Realistic evaluation requires actual large scale deployments

- Proprietary constraints: Production workloads and configurations are often confidential

This is why Martin emphasized dynamic benchmarks like DeathStarBench. We need evaluation methodologies that match the probabilistic, adaptive nature of the systems we’re optimizing.

The dataset challenge is even more acute here than in previous weeks. You can’t just collect a corpus of distributed system configurations. You need telemetry streams, workload traces, failure patterns, and temporal dynamics. The data is continuous, high dimensional, and context dependent.

Setting Up Phase 2

Week 6 also sets up Phase 2’s central question. If AI can co-design software and network topology, can it also co-design hardware and software together?

COSMIC optimizes workload mapping and network topology jointly. But network topology is constrained by available hardware. And hardware design was based on assumptions about workload patterns. The entire stack is interconnected.

Next week, as we transition to Phase 2 (AI for Architecture), we’ll see how these principles extend beyond software into hardware design itself. We’ll explore how AI can:

- Navigate architectural design spaces that dwarf even distributed system complexity

- Predict performance across hardware configurations before silicon exists

- Discover optimizations that span from transistors to training jobs

The determinism to dynamism transition we experienced this week foreshadows an even more profound shift. From optimizing fixed architectures to AI systems that can propose and evaluate entirely new architectural paradigms.

Key Takeaways

Paradigm Shift: Week 6 marks the transition from deterministic single-machine optimization to probabilistic distributed system adaptation. This is a fundamental change in how we think about “correctness” and “performance.”

Co-Design Is Essential: COSMIC demonstrates that optimizing workload and infrastructure together yields breakthroughs impossible from optimizing either alone. The artificial boundaries between layers limit what’s achievable.

AI as Implementation Path: The vast search spaces and dynamic conditions of distributed systems make AI driven optimization not just helpful, but necessary. Traditional techniques simply can’t handle the scale and complexity.

Deployment Is the Bottleneck: The gap between research and production is vast. Infrastructure for safely deploying learned systems is often harder to build than the ML models themselves. This is where industry struggles and where academia has unique opportunities.

Dynamic Systems Need Dynamic Benchmarks: Static benchmarks fail to capture the continuous adaptation that distributed systems require. We need evaluation methodologies that match the probabilistic, time-varying nature of these systems.

Scale Economics Are Shifting: As model scaling shows diminishing returns, system efficiency becomes a competitive advantage. How you use your GPUs matters more than how many you have.

Academic Opportunity: While industry retrofits ML into existing systems, academia can explore first-principles design with ML integration from the start. This is a chance to rethink fundamental abstractions.

Questions for the Road Ahead

As we complete Phase 1 (AI for Software) and prepare for Phase 2 (AI for Architecture), several fundamental questions emerge:

For Researchers: How do we create benchmarks that properly evaluate systems in dynamic, shifting conditions rather than static scenarios? Can we develop formal frameworks for reasoning about learned policies in safety critical systems?

For Practitioners: How do we build the infrastructure needed to safely deploy ML driven optimization at scale? What design patterns enable clean separation between mechanisms and policies?

For Educators: How do we train the next generation to think across traditional abstraction boundaries? What skills matter when AI handles optimization within layers but humans must orchestrate across them?

For the Field: If AI can co-design software and network topology, what else should we be co-designing? How far can we push full stack optimization when AI can reason across domains that previously required separate experts?

The answers to these questions will shape not just distributed systems, but the entire future of computing system design.

The network became the bottleneck when we scaled from one GPU to thousands. Next week, we’ll explore what happens when the architecture itself becomes the optimization target, and AI must reason about hardware design spaces that dwarf even the complexity of distributed systems.

For detailed readings, slides, and materials for this week, see Week 6 in the course schedule.