Week 5: Can LLMs Optimize GPU Performance? From CPU Transparency to GPU Complexity

Over the past four weeks, we’ve been exploring a central question: can AI systems help us optimize performance at scale? We started with the foundational challenges of Architecture 2.0, examined the software engineering reality gap between AI capabilities and real development tasks, and investigated how Google’s ECO system tackles CPU performance optimization in production.

This week, we confront the next frontier: can LLMs optimize GPU performance?

This isn’t just a natural progression from CPU optimization. It’s a qualitatively different challenge. While CPUs offer relatively predictable optimization paths that AI systems like ECO can navigate, GPUs present an entirely different beast. The question isn’t whether GPUs are important (they power every AI breakthrough), but whether AI systems can master the complex, multi-layered optimization challenges that make GPU performance engineering fundamentally harder than anything we’ve discussed so far.

🔑 Key Takeaways

- Architectural Complexity Gap: GPUs are more complex than CPUs, requiring explicit parallelism management, intricate memory hierarchy optimization, and specialized kernel design

- The Transparency Trade-off: While CPUs offer transparent optimization paths, GPUs demand deep architectural understanding but reward it with orders-of-magnitude performance gains

- Kernel Optimization as the New Frontier: GPU kernel optimization challenges performance engineering more so than for CPUs due to the nature of their complex design space, where more sophisticated AI-assisted approaches like multi-turn RL are beginning to show potential

- Production Reality Check: Real-world GPU deployment faces unique challenges around latency, precision, and deterministic behavior that research environments rarely capture

The GPU Revolution: Why AI Changed Everything

Before we can answer whether LLMs can optimize GPU performance, we need to understand what makes GPU optimization so challenging in the first place. The story begins with how the AI boom transformed GPUs from specialized graphics processors into the computational backbone of modern artificial intelligence.

This is more than just scaling up existing approaches. It’s a fundamental shift in how we think about computation itself, driven by the unique demands of machine learning workloads.

Huang’s Law vs Moore’s Law: While Moore’s Law predicts transistor density doubling every ~2 years, Huang’s Law describes GPU AI performance improvements through architectural innovation, not just transistor scaling. This includes specialized units like Tensor Cores, memory bandwidth improvements (HBM evolution), software stack optimizations (cuDNN, TensorRT), precision optimizations, and better parallelism scaling. Unlike Moore’s Law’s focus on transistor count, Huang’s Law captures end-to-end AI workload performance, explaining why GPU optimization has become so critical. The hardware is improving faster than traditional CPU scaling, but only if software can exploit these architectural advances effectively.

NVIDIA’s data center revenue has grown dramatically, driven almost entirely by AI demand. This transformation wasn’t inevitable. It began with a fortunate accident. In 2012, when Alex Krizhevsky used NVIDIA GPUs to win ImageNet with AlexNet, NVIDIA’s gaming GPUs accidentally became the foundation of the deep learning revolution. The company quickly recognized this opportunity, pivoting from optimizing for graphics workloads to AI workloads. The introduction of Tensor Cores in the Volta architecture (2017) marked NVIDIA’s full commitment to AI, providing specialized units for the mixed-precision matrix operations that dominate neural network training.

Every major language model, from GPT-4 to Claude to Gemini, relies on massive GPU clusters for both training and inference. As we discussed in Week 2’s exploration of fundamental challenges, the demand explosion for specialized hardware has created more design work than our industry has architects to handle, and GPUs sit at the epicenter of this demand.

But this AI-driven GPU adoption has revealed profound challenges that go far beyond traditional graphics workloads. Modern AI applications don’t just need raw computational power; they need it delivered with precise control over memory access patterns, numerical precision, and execution scheduling. This creates a multi-layered software stack that makes CPU optimization look straightforward by comparison.

This brings us to our central question: “Can LLMs optimize GPU performance?” If LLMs can navigate this landscape, managing parallel execution, memory hierarchies, and domain-specific optimizations, they could unlock performance gains that no human expert could achieve manually. But if they can’t, we’re stuck with the current bottleneck: too few GPU optimization experts for too much demand.

Historical Context: Learning from Past Complexity Challenges

To answer this question, we need to understand how the industry has previously tackled similar challenges. The evolution of heterogeneous computing offers crucial lessons, beginning with pioneering systems that first challenged the CPU-centric computing model.

These historical examples reveal what LLMs must overcome to succeed at GPU optimization and why some approaches to managing architectural intricacy have failed while others have thrived.

The IBM Cell Processor: When Complexity Overwhelms Performance

The story begins with systems like IBM’s Cell processor, introduced in 2005 for the PlayStation 3. Cell represented one of the first serious attempts at heterogeneous computing, combining a traditional PowerPC core with eight specialized Synergistic Processing Elements (SPEs).

The Cell processor was a glimpse into the future: massive parallel processing power, but only if programmers could master its complex programming model. Developers had to explicitly manage data movement between different memory spaces, carefully orchestrate parallel execution across heterogeneous cores, and optimize for radically different execution models within a single system.

The performance potential was enormous. Cell could deliver supercomputer-class performance for certain workloads, but the programming complexity proved prohibitive for most developers.

The Cell processor’s commercial failure taught the industry a crucial lesson: raw performance isn’t enough if the programming model is too complex. This lesson directly influenced GPU evolution. CUDA’s success came partly from providing higher-level abstractions that made GPU programming accessible to a broader developer community.

For LLMs tackling GPU optimization, Cell’s failure offers a crucial insight: complexity that overwhelms human developers might actually favor AI systems. LLMs don’t get frustrated by explicit memory management or complex parallel coordination. They can potentially navigate these challenges systematically in ways humans cannot.

CUDA’s Revolution: Making Complexity Manageable

CUDA (Compute Unified Device Architecture) is NVIDIA’s parallel computing platform and programming model that allows developers to use GPUs for general-purpose computing, not just graphics. Think of it as the bridge that transforms a graphics card designed for rendering pixels into a massively parallel processor that can accelerate everything from machine learning to scientific simulations. CUDA provides both the low-level hardware interface and the high-level programming abstractions that make GPU programming accessible to developers.CUDA’s Academic Influences: CUDA’s development was influenced by academic research in GPU computing, including Stanford’s Brook project in the early 2000s, which explored stream programming concepts for GPUs. Before CUDA, developers had to express general-purpose computations as graphics operations, essentially tricking the GPU into doing math by pretending it was rendering pixels. CUDA was introduced in 2006 as a departure from this approach. The “Compute Unified Device Architecture” name unified graphics and compute workloads under a single programming model, transforming GPUs from specialized graphics processors into general-purpose parallel computers. Academic research has continued to influence GPU architecture development, with concepts like systolic arrays (pioneered by researchers like H.T. Kung) later appearing in specialized processors like Google’s TPUs. This illustrates how academic research in computer systems often provides foundational insights that eventually enable new industries and technologies. But CUDA isn’t just a programming language. It’s an entire ecosystem that learned from Cell’s mistakes by providing manageable abstractions while still exposing the performance potential of parallel hardware.

The CUDA Moat: When Success Creates Lock-In

But CUDA’s remarkable success story has an unexpected twist. By building such a comprehensive and optimized ecosystem, NVIDIA inadvertently created what many call the “CUDA moat”, a competitive barrier that makes it extremely difficult for developers to switch to alternative hardware platforms, even when those platforms might offer better price-performance ratios for specific workloads.

The depth of this moat becomes apparent when you consider what porting a CUDA application really entails. It’s not just translating kernel code from CUDA C++ to alternatives like OpenCL (the cross-platform standard) or AMD’s ROCm (Radeon Open Compute platform). It’s recreating years of optimization work embedded in cuDNN, cuBLAS, and countless other specialized libraries.

A transformer model that achieves optimal performance on NVIDIA hardware through carefully tuned cuDNN operations might run significantly slower on AMD or Intel GPUs, not because the hardware is inferior, but because the software ecosystem lacks equivalent optimization depth. AMD has ROCm and Intel has oneAPI, but these platforms are still catching up to NVIDIA’s decade-plus head start in building optimized libraries for AI workloads.

This creates a fascinating paradox in the current AI hardware Cambrian explosion. We’re witnessing unprecedented innovation in AI accelerators, from Google’s TPUs and Amazon’s Trainium to startups like Cerebras, Graphcore, and SambaNova—but most AI workloads remain locked to NVIDIA hardware not by technical necessity, but by software ecosystem dependencies. The result is that hardware innovation often goes unutilized because the software optimization gap is too large to bridge manually.

The question becomes: how do we break free from this hardware lock-in? The manual approach of hiring teams of specialists to hand-optimize for each hardware platform is prohibitively expensive and doesn’t scale. This is where our central question becomes urgent: if LLMs could automatically generate optimized implementations across diverse architectures, they could break down the barriers that currently lock workloads to specific vendors. The CUDA moat exists because optimization expertise is scarce. But what if LLMs could democratize that expertise?

The Hennessy & Patterson Vision: Domain-Specific Architecture Era

The transition from CPU-centric to heterogeneous computing received its most influential articulation in John Hennessy and David Patterson’s 2017 Turing Award lecture, “A New Golden Age for Computer Architecture”. Their central insight was that the end of Moore’s Law and Dennard scaling necessitated a fundamental shift toward domain-specific architectures.

As Hennessy and Patterson observed, “The end of Moore’s Law and Dennard scaling, plus the slowdown in performance gains for standard microprocessors, is not a cause for despair, but an opportunity.” Their vision was that specialized architectures could deliver the performance improvements that general-purpose processors could no longer provide.

But here’s the crucial insight that connects to our current GPU complexity challenge: domain-specific specialization means you often need deep domain knowledge to extract performance. This creates a fundamental challenge for optimization: you need expertise in both the application domain and the underlying hardware architecture.

This observation is profound when applied to GPU optimization. Unlike CPU optimization, where general principles often suffice, GPU optimization requires deep understanding of specific domains. whether that’s computer graphics, machine learning, scientific computing, or cryptocurrency mining. Each domain has different computational patterns, memory access requirements, and performance bottlenecks.

This brings us to the central challenge that motivated our course: if optimal performance requires domain-specific expertise, but we don’t have enough domain experts to meet the demand, how do we scale specialized optimization? This is precisely where LLMs become potentially transformative. They offer the possibility to democratize expert-level optimization knowledge across diverse GPU architectures and domains.

The Complexity Challenge: Understanding GPU vs CPU Optimization

To understand what LLMs must master to succeed at GPU optimization, we need to examine the specific technical challenges that make GPU performance engineering so different from CPU optimization. When students first encounter GPU programming, they often think it’s just parallel CPU programming with more cores. This misconception dissolves quickly when they discover the intricate software ecosystem required to make GPUs productive and the fundamental differences in how optimization must be approached.

The GPU Software Stack: Layers Upon Layers

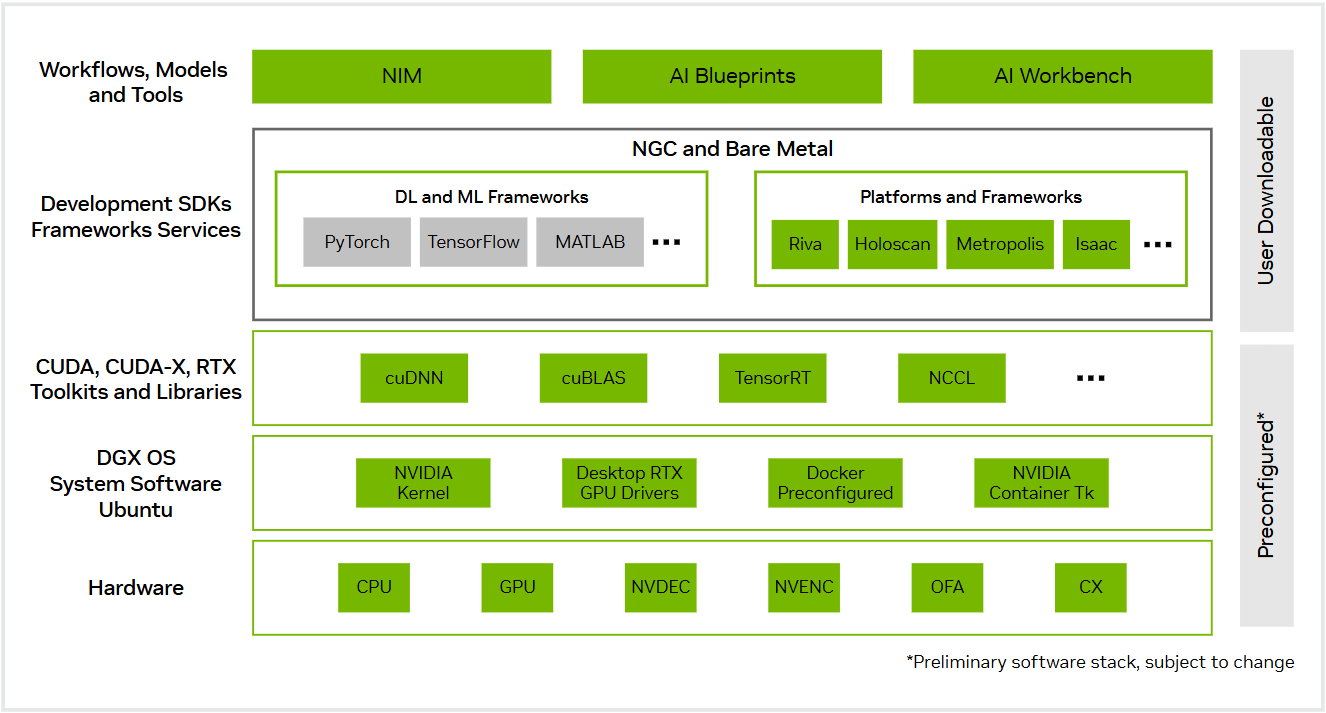

The reality is that modern GPU computation involves a sophisticated stack of abstractions, each adding both power and complexity:

The Foundation Layer: CUDA Runtime manages device memory, kernel launches, and synchronization. CUDA Driver provides low-level hardware interface and resource management. PTX (Parallel Thread Execution) offers a virtual instruction set that provides portability across GPU generations. SASS (Streaming ASSembler) represents the actual machine code that runs on GPU hardware.

The Optimization Layer: Above CUDA sits a layer of highly optimized libraries that implement common computational patterns:

-

cuDNN (CUDA Deep Neural Network library) provides optimized implementations of neural network primitives: convolutions, pooling, normalization, and activation functions. These aren’t just convenience functions; they represent years of optimization work by NVIDIA’s engineers.

-

cuBLAS (CUDA Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms) handles matrix operations that form the backbone of most AI workloads. Modern transformer models spend the majority of their time in matrix multiplications, making cuBLAS performance critical.

-

Cutlass (CUDA Templates for Linear Algebra Subroutines) represents the cutting edge, a template library that generates optimized CUDA kernels for specific hardware and problem sizes.

The Framework Layer: At the top of the stack sit machine learning frameworks like PyTorch and TensorFlow, which hide most GPU complexity from end users. But this abstraction comes at a cost. when performance problems arise, debugging often requires understanding the entire stack, from Python code down to GPU assembly.

This foundation alone represents enormous complexity. Unlike CPU programming where the operating system handles most hardware details, GPU programming requires explicit management of memory hierarchies, thread scheduling, and hardware resources.

The Great Divide: CPU Transparency vs GPU Complexity

The fundamental difference between CPU and GPU optimization reflects a broader shift in computing philosophy. CPU architectures prioritize ease of programming and predictable performance, while GPU architectures prioritize raw computational throughput, but only for programs that can exploit their parallel nature effectively.

CPU Optimization: Forgiving and Predictable: CPU optimization, while certainly intricate, operates within a relatively predictable framework. When we discussed ECO’s success at Google in Week 4, we saw how AI systems could identify performance anti-patterns like unnecessary allocations and redundant operations.

These optimizations work because CPU architectures are designed to be somewhat forgiving. Branch predictors, out-of-order execution, and sophisticated caching mechanisms help smooth over suboptimal code patterns. As Charles Leiserson noted in his influential “There’s Plenty of Room at the Top” paper, CPU performance engineering benefits from decades of mature tooling and well-understood optimization principles.

The relationship between code quality and performance is largely monotonic and predictable: write better code, get better performance.

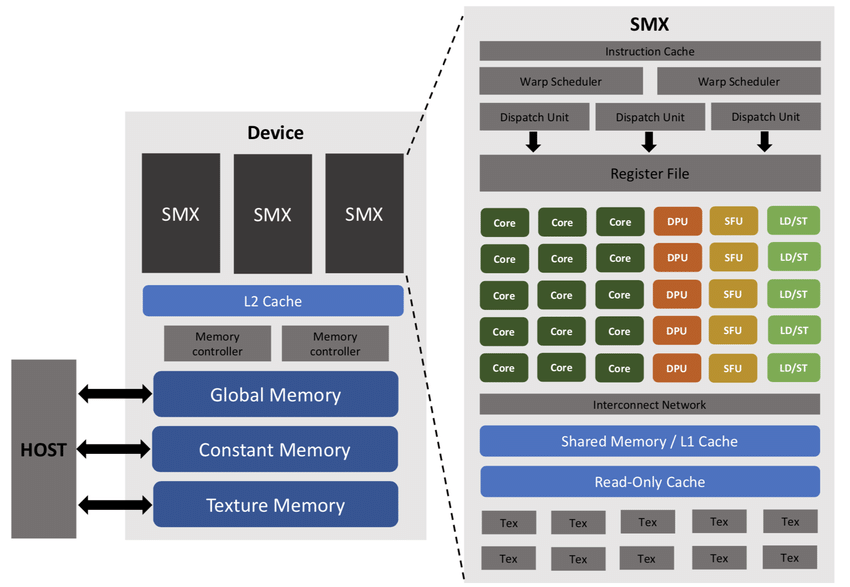

GPU Optimization: Unforgiving but Transformative: GPUs shatter this comfortable predictability. GPU architectures are designed around fundamentally different principles: massive parallelism, explicit memory management, and specialized execution units that can deliver extraordinary performance, but only when used correctly. The performance cliff is steep. Naive GPU code often performs worse than CPU equivalents, while optimized GPU code can deliver dramatic speedups.

Consider the challenges that emerged from our class discussions:

Memory Bandwidth Dominance: Unlike CPUs where compute often dominates, modern GPU performance is frequently memory-bound. Memory bandwidth has become more important than raw compute power in modern GPUs. This inverts traditional optimization thinking. Instead of optimizing algorithms for computational efficiency, GPU optimization often centers on minimizing memory movement and maximizing data reuse.

Precision and Specialization Trade-offs: GPUs offer multiple numerical precision modes, from 32-bit floating point down to 8-bit integers and specialized formats like bfloat16, each with different performance characteristics. Lower precision can dramatically improve throughput, but the trade-offs are complex and workload-dependent. Blindly pursuing lower precision can actually hurt performance in many scenarios due to diminishing returns and accuracy concerns.

Algorithmic Restructuring Requirements: While CPU optimization often involves tweaking existing code, GPU optimization frequently requires rethinking algorithms from scratch. The difference between a naive GPU kernel and an optimized one can be orders of magnitude, far exceeding the typical gains possible in CPU optimization.

To appreciate the intricacy of this process, consider that a state-of-the-art matrix multiplication kernel involves understanding GPU memory hierarchies, warp-tiling techniques, tensor cores, asynchronous pipelines, and even space-filling curves like Hilbert curves for optimal memory access patterns.

This layered complexity explains why GPU performance engineering is fundamentally different from CPU optimization. As we learned from Week 3’s discussion of the software engineering reality gap, AI systems excel at isolated problems but struggle with complex, interconnected systems. The GPU software stack represents exactly this kind of complex system where optimization decisions at one layer can have unexpected effects at others.

But here’s the paradox: while this complexity makes GPU optimization harder for humans, it might actually make it more suitable for AI assistance. The very characteristics that challenge human developers (managing thousands of parallel threads, optimizing across multiple memory hierarchies, navigating complex trade-offs between precision and performance) are exactly the kinds of multi-dimensional optimization problems where AI systems can potentially excel.

AI-Assisted Breakthroughs: From Benchmarking to Multi-Turn RL

The complexity we’ve explored creates both a challenge and an opportunity for AI-assisted optimization. Unlike CPU optimization where incremental improvements are the norm, GPU optimization’s steep performance cliffs mean that AI systems that can navigate this complexity have the potential to deliver transformative performance gains. Recent research has begun to tackle this challenge systematically.

KernelBench: Systematizing the Real-World Challenge

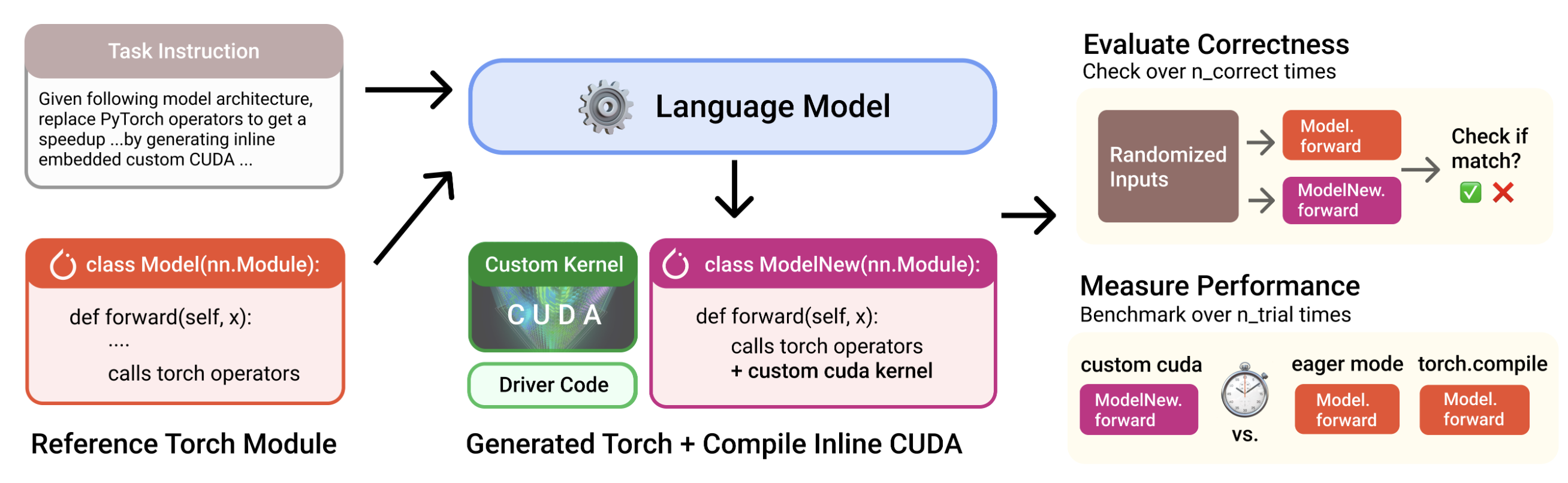

The KernelBench project from Stanford represents a crucial step toward systematizing GPU performance evaluation in ways that directly translate to practical impact. Unlike synthetic benchmarks that test isolated capabilities, KernelBench focuses on “a real-world engineering environment” with 250 carefully selected PyTorch ML workloads that represent actual production scenarios.

The benchmark introduces a novel evaluation metric called fast_p, which measures “the percentage of generated kernels that are functionally correct and offer a speedup greater than an adjustable threshold p over baseline.” This metric captures the dual challenge of GPU optimization: not only must kernels be correct, but they must deliver meaningful performance improvements to justify their complexity.

The results reveal the scope of the challenge facing AI-assisted optimization. Even frontier reasoning models struggle to match PyTorch baselines in most cases, a sobering reminder that despite impressive capabilities in other domains, current AI systems struggle with the complex, multi-layered optimization challenges that GPU programming presents.

KernelBench’s focus on real PyTorch workloads is particularly significant because it bridges the gap between research and practice. As the authors note, “making progress on the introduced benchmark directly translates to faster practical kernels.” This connection to real-world impact addresses one of the key challenges we identified in Week 2’s discussion of fundamental challenges: ensuring that research advances translate to practical benefits.

Kevin: Multi-Turn RL and Measurable Breakthroughs

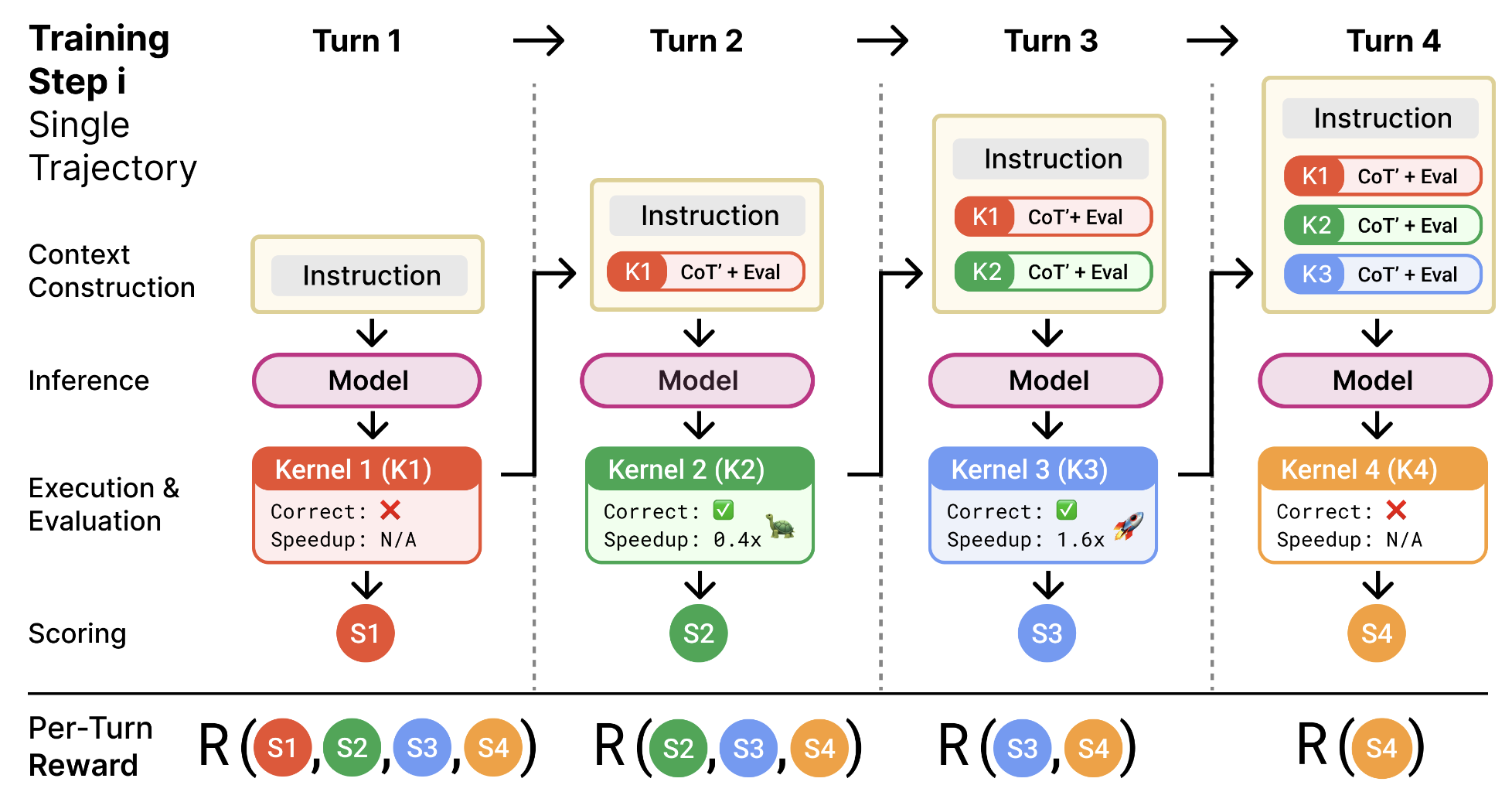

The complexity of GPU optimization also explains why traditional optimization approaches often fall short. This brings us to one of the most exciting developments in AI-assisted performance engineering: Kevin (K(ernel D)evin), “the first model trained with multi-turn RL for CUDA kernel generation and optimization.”

Kevin’s innovation lies in recognizing that “writing GPU kernels is a challenging task and critical for AI systems’ efficiency” that is “highly iterative: domain experts write code and improve performance through execution feedback.” Traditional single-turn approaches miss this iterative nature entirely, treating kernel generation as a one-shot problem rather than the iterative refinement process that human experts actually use.

The results are compelling and measurable. Kevin demonstrates significant improvements over its base model:

- Correctness improvements: Substantial gains in generating functional CUDA kernels

- Performance gains: Meaningful speedups over PyTorch Eager baseline

- Competitive performance: Surpassing other frontier models

But perhaps most importantly, Kevin’s multi-turn RL framework addresses “unique challenges encountered in real-world settings, such as learning from long trajectories and effective reward attribution across turns.” This tackles a fundamental problem in AI-assisted optimization: how to learn from the complex, multi-step feedback loops that characterize expert performance engineering.

Kevin’s approach explicitly incorporates the iterative nature of expert optimization:

- Generate Initial Kernels: Create baseline implementations based on high-level specifications

- Execute and Profile: Run the kernels and collect detailed performance metrics

- Analyze Bottlenecks: Identify specific performance limitations (memory bandwidth, occupancy, instruction throughput)

- Iteratively Refine: Generate improved versions that address identified bottlenecks

- Repeat Until Convergence: Continue the cycle until performance plateaus

The research also reveals important insights about test-time scaling. The Kevin paper shows that scaling serial refinement is more beneficial than parallel sampling. This suggests that giving AI systems more opportunities to iterate and refine solutions is more effective than generating many parallel alternatives, a finding that aligns with how human experts approach complex optimization problems.

The Kevin breakthrough is particularly significant because it addresses the core challenge identified by Hennessy and Patterson: how to democratize domain-specific expertise. By learning to mimic expert optimization workflows and demonstrating measurable improvements in both correctness and performance, Kevin offers concrete evidence that AI systems can begin to match expert-level GPU optimization capabilities.

Production Reality: Insights from the Trenches

While research systems like Kevin demonstrate the potential of AI-assisted GPU optimization, our Wednesday discussion with Sasha Rush provided crucial insights into the production realities of deploying these techniques at scale.

Sasha Rush is a Professor at Cornell Tech and was previously a Professor at Harvard University. His research spans machine learning, natural language processing, and efficient neural network implementations. Rush is known for his work on sequence-to-sequence models, attention mechanisms, and neural machine translation. He’s also a prolific open-source contributor, having developed tools like OpenNMT and Annotated Transformer. His academic rigor combined with practical engineering experience makes him uniquely positioned to bridge research and production challenges in AI-assisted programming.

Sasha Rush is a Professor at Cornell Tech and was previously a Professor at Harvard University. His research spans machine learning, natural language processing, and efficient neural network implementations. Rush is known for his work on sequence-to-sequence models, attention mechanisms, and neural machine translation. He’s also a prolific open-source contributor, having developed tools like OpenNMT and Annotated Transformer. His academic rigor combined with practical engineering experience makes him uniquely positioned to bridge research and production challenges in AI-assisted programming.

Professor Rush’s perspective from Cursor, a company building AI-powered development tools used by millions of developers, illuminated the gap between research demonstrations and production deployment. (Note: The views expressed are Professor Rush’s own and do not necessarily reflect Cursor’s official positions.)

Several key insights emerged from our class discussions:

The Latency Imperative

In research settings, we often focus on throughput optimization, maximizing the performance of long-running computations. But production AI systems face a different constraint: latency. Rush emphasized that maintaining low latency in the prediction process is crucial for AI coding assistants. Users expect near-instantaneous responses, which constrains the optimization techniques that can be applied in practice.

Rush’s perspective on this challenge was particularly insightful. He noted that the cost of efficient inference scheduling, both for rollout generation and reward computation, often dominates the training pipeline. This observation captures a fundamental tension in production AI systems: the very optimizations that make training efficient can create bottlenecks during inference, where user-facing latency requirements are paramount.

This latency requirement fundamentally changes the optimization problem. While research systems can afford to spend significant time optimizing kernels offline, production systems must balance optimization quality against response time. The most sophisticated kernel optimization might be worthless if it takes too long to generate.

Precision and Determinism Challenges

Rush also highlighted the challenges of aligning training and inference systems with different numerical precision trade-offs. In research, we can often accept some variability in results as long as average performance improves. But production systems require deterministic behavior. The same input must always produce the same output, regardless of the underlying hardware or optimization choices.

This determinism requirement creates tension with many GPU optimization techniques. Different GPU architectures may require different kernel implementations for optimal performance, but users expect consistent behavior across different hardware. Balancing performance optimization with behavioral consistency remains an ongoing challenge.

The Infrastructure Reality

Perhaps most importantly, Rush emphasized the infrastructure requirements for production GPU optimization. The challenges of dealing with long-running tasks and the need for efficient inference and training workflows mean that successful deployment requires far more than just good optimization algorithms.

Rush offered a particularly thoughtful reflection on the broader implications: can models help decide which rollouts to prioritize, or how to allocate compute across competing objectives? This question gets to the heart of a meta-optimization challenge: using AI not just to optimize individual kernels, but to optimize the optimization process itself. It’s a recursive problem that highlights how AI-assisted performance engineering might evolve beyond current approaches.

This echoes the lessons we learned from ECO’s deployment at Google: the infrastructure for safely deploying AI-generated optimizations is often more complex than the optimization algorithms themselves.

Reflecting on Our Journey: From Architecture 2.0 to GPU Reality

GPU performance engineering represents an inflection point in our five-week exploration. Unlike CPU optimization, where AI systems must compete with decades of mature tooling, GPU optimization presents a domain where complexity actually favors AI assistance.

The characteristics that make GPU programming challenging for humans create opportunities for AI systems:

- Complexity favors AI: The multi-layered software stack and intricate optimization interactions are exactly the kind of complex systems where AI can provide disproportionate value

- Human expertise is scarce: The domain-specific knowledge required for optimal GPU programming is rare and expensive, creating clear value for AI democratization

- Feedback loops are rich: GPU programming provides the kind of verifiable, measurable feedback that enables effective AI learning

- The stakes are high: GPU optimization directly impacts the cost and accessibility of AI systems, making improvements economically valuable

This explains why we’re seeing breakthroughs like Kevin’s multi-turn RL approach in GPU optimization before similar advances in other domains. The characteristics that make GPU programming challenging for humans (explicit parallelism management, complex memory hierarchies, domain-specific optimization patterns) are precisely the characteristics that create opportunities for AI systems.

Looking Ahead: The Broader Implications

The transition from CPU to GPU optimization represents more than just a change in target architecture. It represents a fundamental shift in the nature of performance engineering itself. As we move toward increasingly specialized hardware (TPUs, neuromorphic chips, quantum processors), the lessons we’re learning about GPU optimization will become even more relevant.

The key insight is that performance engineering is becoming less about optimizing within fixed architectural constraints and more about co-designing algorithms and architectures to achieve optimal performance. AI systems that can reason across these traditional boundaries, that can simultaneously optimize code and suggest architectural improvements, represent the future of performance engineering.

🎯 Key Takeaways

- Complexity Creates Opportunity: GPU optimization's complexity makes it an ideal domain for AI assistance, where systematic exploration can discover optimizations beyond human capability

- Iterative Approaches Win: Multi-turn RL approaches like Kevin demonstrate that mimicking expert iterative optimization processes is more effective than single-shot generation

- Production Constraints Are Real: Latency, determinism, and portability requirements significantly constrain the optimization techniques that can be deployed in practice

- Historical Lessons Matter: Learning from Cell's complexity failure and CUDA's abstraction success guides how we approach GPU optimization challenges

- Infrastructure Enables Innovation: Robust profiling, deployment, and monitoring infrastructure is essential for safely deploying AI-generated optimizations at scale

Questions for the Road Ahead

As we continue our exploration of AI-assisted performance engineering, several fundamental questions emerge:

For Researchers: How do we build AI systems that can reason about the complex interactions between algorithm design, memory access patterns, and specialized hardware units? Can we develop approaches that automatically discover when algorithmic restructuring can unlock new hardware capabilities?

For Practitioners: How do we balance the pursuit of optimal performance with the need for maintainable, portable code? What infrastructure is needed to safely deploy AI-generated optimizations in production environments with diverse hardware configurations?

For Educators: How do we teach the next generation of performance engineers to think across traditional abstraction boundaries? What skills will be essential when AI systems can handle routine optimization tasks?

For the Field: As hardware becomes increasingly specialized and diverse, how do we ensure that optimization techniques remain accessible to developers who aren’t hardware experts? Can AI systems democratize access to expert-level optimization capabilities?

The answers to these questions will determine whether AI-assisted performance engineering becomes a transformative force for all of computing or remains a competitive advantage for a select few organizations with the resources to build sophisticated optimization infrastructure.

Next week, we’ll continue exploring these themes as we delve deeper into the practical realities of deploying AI-assisted optimization in production environments. The journey from research breakthrough to production deployment remains challenging, but the progress we’ve seen in GPU optimization offers hope that we’re beginning to crack the code on AI-assisted performance engineering.

For detailed readings, slides, and materials for this week, see Week 5 in the course schedule.