Week 4: Can AI Optimize Production Code? From Contest Winners to Google's ECO

On September 12, 2024, AI models demonstrated stunning capabilities at the International Collegiate Programming Contest (ICPC). OpenAI’s GPT-5 managed to achieve a perfect score, answering 12 out of 12 problems, a performance akin to winning a gold medal. Not to be outdone, Google’s Gemini 2.5 Deep Think solved 10 of the 12 algorithmic problems, a result that would have secured second place overall in the competition. Headlines proclaimed AI’s dominance over human programmers.

Yet this week in our class, we discussed why these contest victories, impressive as they are, barely scratch the surface of what it takes to deploy AI for real software optimization.

Why Performance Optimization Matters More Than Ever

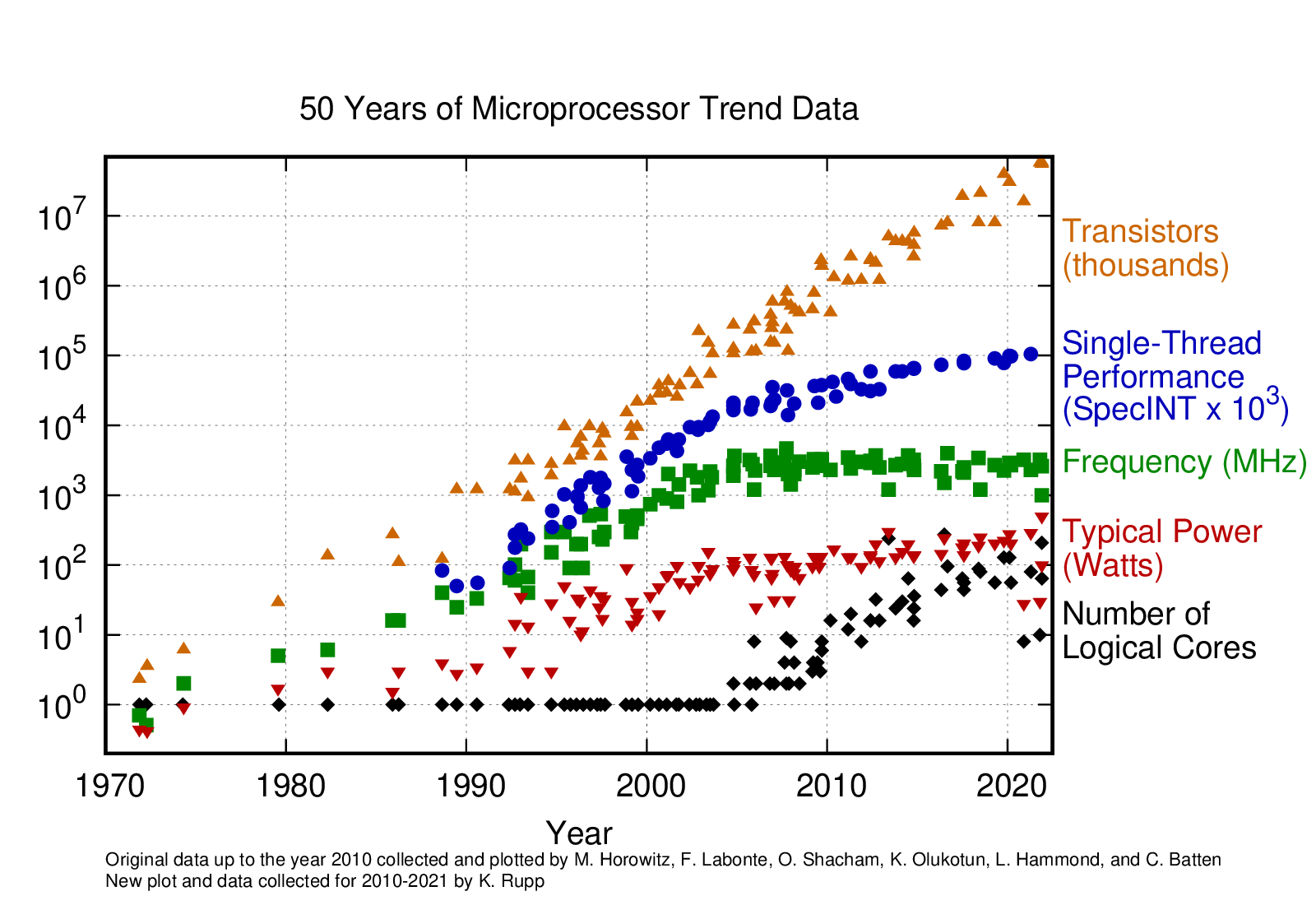

Before exploring the complexities of production optimization, we must understand why performance engineering has become existential for modern computing. For decades, we enjoyed a “free lunch” from Moore’s Law: processors got faster every year, and software automatically ran better on new hardware. That party ended around 2006. This dramatic divergence: transistors still doubling but performance is one of the most significant inflection points in computing history. The Physics Behind the Plateau: Dennard Scaling, which allowed smaller transistors to run at the same power density, broke down around 2006 due to current leakage and heat dissipation limits. Clock frequencies hit a wall at approximately 4GHz because pushing higher would require exponentially more power and generate unsustainable heat. This forced the industry to pivot from faster cores to more cores, fundamentally changing how we must approach performance. As Leiserson observed, this plateau represents not an end but a beginning—the start of the “performance engineering era” where software optimization becomes the primary driver of computational progress.

Figure: 50 years of microprocessor trend data showing the dramatic plateaus in single-thread performance and frequency around 2005-2006, while transistor count continues exponential growth. The divergence of these trends marks the end of automatic performance scaling and the beginning of the performance engineering era. Source: Karl Rupp’s Microprocessor Trend Data

Figure: 50 years of microprocessor trend data showing the dramatic plateaus in single-thread performance and frequency around 2005-2006, while transistor count continues exponential growth. The divergence of these trends marks the end of automatic performance scaling and the beginning of the performance engineering era. Source: Karl Rupp’s Microprocessor Trend Data

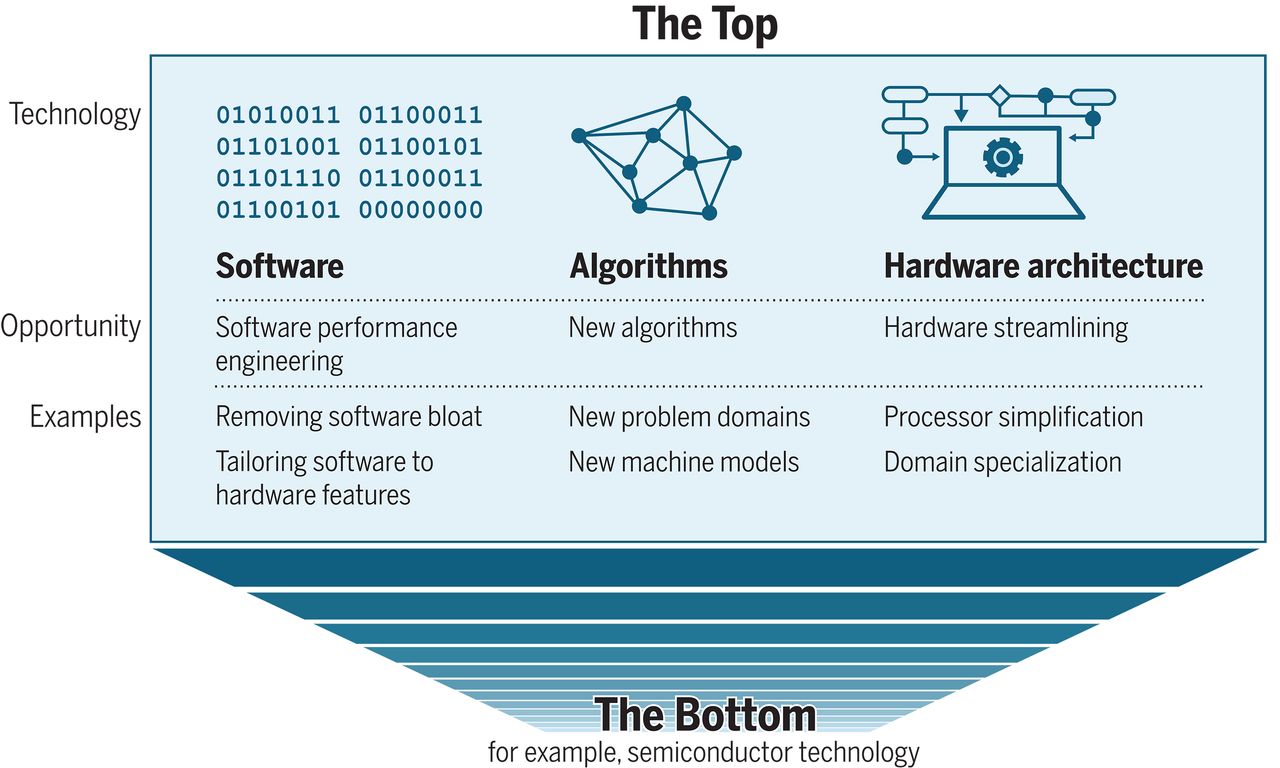

Charles Leiserson’s influential 2010 paper “There’s Plenty of Room at the Top” captured the implications perfectly. While Moore’s Law continues for transistor density, the end of Dennard scaling means we can no longer automatically convert those transistors into performance gains. But here’s the crucial insight: Leiserson argued this isn’t a limitation: it’s an opportunity for performance engineering to become the primary driver of computational progress.A Performance Engineer’s Joke: A friend who leads a performance optimization team at a large tech company once joked that the end of Moore’s Law was the best thing that ever happened to them. Suddenly, their team’s work became mission-critical. You could no longer just wait a year for hardware to get faster; every gain had to be earned through clever engineering.

The “room at the top” refers to the massive performance gap between what current software achieves and what the underlying hardware is theoretically capable of delivering. To illustrate this gap, the paper provides a striking example: a standard matrix-multiplication program written in Python took 7 hours to run, but after performance engineering, the same task on the same hardware finished in just 0.41 seconds—a speedup of over 60,000x. This gap is precisely what motivates the entire field of AI assisted performance optimization.

The critical question isn’t just acknowledging this gap, but determining how to systematically close it. Historically, this has been the domain of bespoke, human driven performance engineering: a time consuming and often unscalable process. The promise of modern AI is to harness this untapped potential not through manual effort, but by creating systems that can learn, identify, and implement optimizations automatically at previously unimaginable scale.

The implications are profound: software optimization is no longer optional—it has become existential. When hardware scaling no longer delivers automatic speedups, every performance gain must be earned through better algorithms, smarter data structures, and more efficient code.

Leiserson identified three primary opportunities for closing this performance gap—for reaching toward that “room at the top”:

- Algorithmic improvements - Often delivering 10-1000x speedups, far exceeding any hardware improvement

- Better parallelization strategies - Efficiently utilizing the multicore processors we now have instead of faster ones

- Hardware software co-design - Optimizing across the full computing stack rather than treating hardware and software separately

These aren’t just theoretical opportunities—they’re the exact challenges that AI assisted optimization systems like ECO are beginning to tackle at scale.

This is why companies like Google build systems like ECO that can squeeze out even small percentage improvements across their massive codebases. Each optimization represents progress toward closing what Leiserson called the “performance gap”—the chasm between theoretical hardware capabilities and actual software performance.

This blog captures our class discussion with guest speaker Amir Yazdanbakhsh from Google DeepMind, who shared insights from his team’s work on performance optimization research.Amir Yazdanbakhsh is a computer architect and researcher at Google DeepMind. You can find more about his work on Google Scholar and his contributions to projects like Pie4Perf. The views expressed are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer. All topics discussed were already in the public domain. The discussion illuminated a shift in focus: while last week we explored the software engineering reality gap between contest-winning AI and real development tasks, this week we examine performance engineering—the specialized discipline of making code run faster and more efficiently at scale.

Software Engineering vs Performance Engineering: Understanding the Distinction

Before diving into the technical details, it’s crucial to understand how this week’s focus differs from last week’s exploration. While both deal with AI assisted code improvement, they address fundamentally different aspects of software development:

| Aspect | Software Engineering | Performance Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Build correct, maintainable, scalable software systems | Optimize code for speed, efficiency, and resource utilization |

| Focus Areas | Architecture, design patterns, testing, debugging, team collaboration | Algorithmic optimization, memory management, CPU utilization, profiling |

| Success Metrics | Functionality, reliability, maintainability, developer productivity | Execution speed, memory usage, throughput, latency |

| Typical Problems | Feature implementation, bug fixes, code organization, API design | Bottleneck identification, cache optimization, parallel processing |

| AI Challenges | Understanding requirements, maintaining code quality, team workflows | Identifying optimization opportunities, measuring heterogeneous hardware impact |

Last week, we examined how AI struggles with the broader software engineering challenges, including understanding system context, maintaining code quality, and integrating into development workflows. This week, we narrow our focus to performance engineering: the specialized discipline of making code run faster and more efficiently, particularly at the massive scales where even small improvements can save millions of dollars in compute costs.

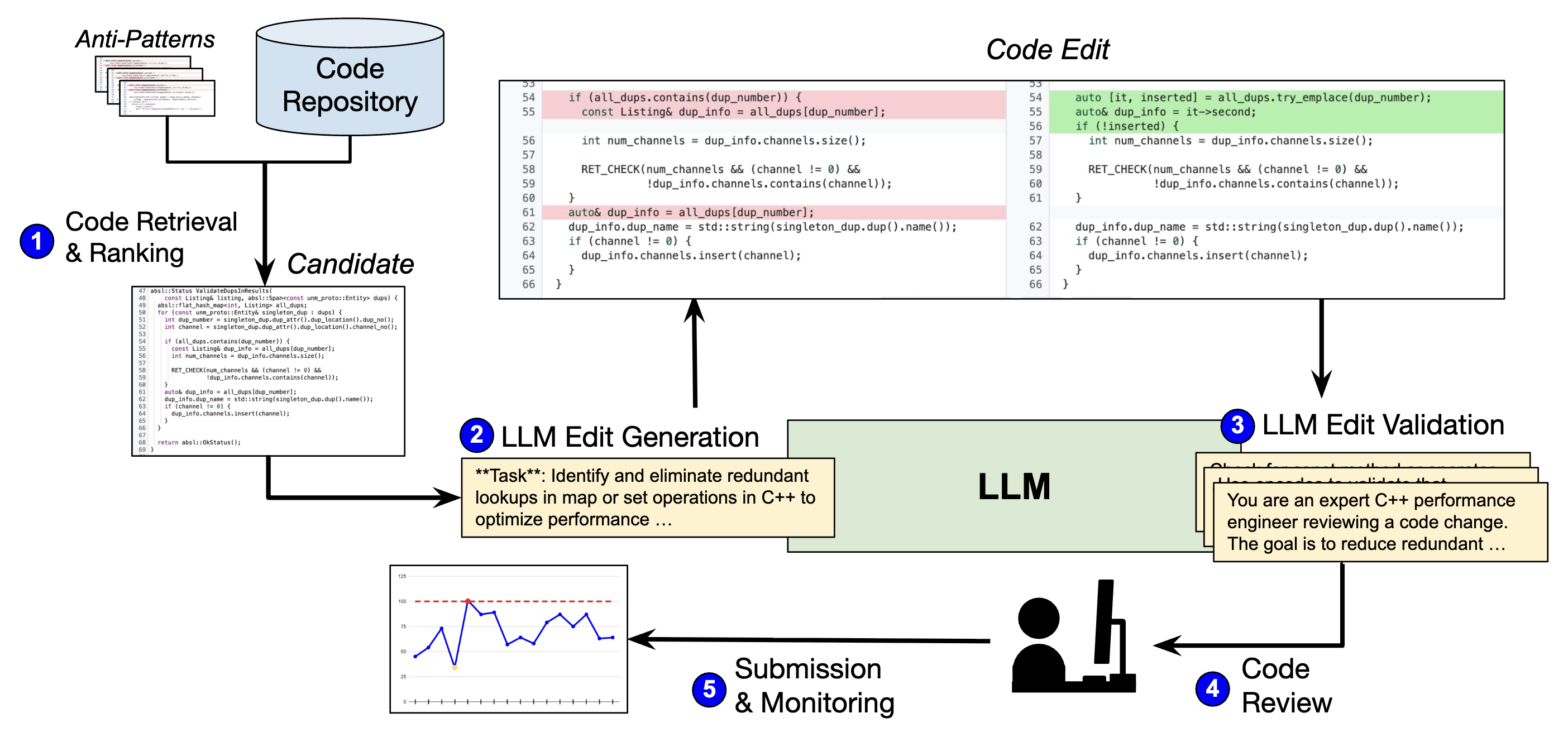

By examining two systems that represent opposite ends of the AI code optimization spectrum: the research from “Learning Performance-Improving Code Edits”The “Learning Performance-Improving Code Edits” paper introduces Pie4Perf, a benchmark and dataset for learning performance-improving code edits. It contains 77,265 Python programs with performance improvements, designed to evaluate LLMs’ ability to optimize code. The dataset includes both synthetic problems and real-world optimizations extracted from competitive programming and open-source repositories. and Google’s production ECO system—we can understand why performance engineering presents unique challenges for AI systems.

These two systems illustrate the full spectrum of challenges in AI assisted code optimization. The Pie4Perf research represents the controlled end: a study designed to discover effective optimizations on small, isolated code pieces. ECO represents the production extreme: a Google-scale system where AI agents must collaborate with software engineers in a massive, interconnected codebase serving billions of users.

ECO focuses on specific categories of performance anti patterns that Google researchers identified from mining historical commits: unnecessary allocations, redundant map operations, missing vector reserves, unnecessary copies, and missing std::moves. These might sound like small optimizations, but when applied across Google’s entire codebase, they result in massive aggregate savings. This spectrum (from controlled research environment to production reality) reveals the fundamental challenges that any practical AI optimization system must overcome.

🔑 Key Takeaways

- Contest vs. Reality: AI that wins programming competitions faces entirely different challenges when optimizing real software systems where changes can break interconnected services

- Infrastructure is Everything: Successful AI code optimization requires massive verification systems, continuous monitoring, and rollback mechanisms that most organizations don't have

- Humans Still Essential: Even Google's most advanced AI optimization system requires human developers to review every change before it goes live

- The Verification Problem: While contest problems need only pass test cases, production code changes must be proven safe across millions of lines of interconnected software

The Research to Production Reality Gap

The class discussion offered a compelling narrative on the journey from academic research to production deployment, revealing just how different these two worlds are.

From the research side, our guest speaker discussed work like “Learning Performance Improving Code Edits,” a collaborative project where the team explored the question: Can large language models optimize code performance? As Amir explained from their experience, “When we were designing Pie4Perf, the scope of the benchmark is very, very limited. We’re looking at a very narrow set of problems with a very limited context, trying to see the feasibility of applying LLMs for solving a particular problem that humans are relatively good at.”

Think of this research as a controlled laboratory experiment. Researchers fed the AI system small, isolated code snippets with clear performance problems, such as a function that uses an inefficient sorting algorithm or makes unnecessary database calls. The AI’s job was straightforward: make the code faster while keeping it functionally correct. Success was measured simply: does the optimized code pass the same tests while running faster?

This approach worked beautifully in the research setting. The AI could focus on algorithmic improvements: replacing bubble sort with quicksort, eliminating redundant calculations, optimizing loops. These are the kinds of clean, well defined optimizations that translate well to academic papers.

But then came the reality check. When Google decided to scale this approach to their actual production systems with ECO (Efficient Code Optimization), “a lot of challenges come into play,” as Amir noted. The transition from research prototype to production system revealed a fundamental truth: optimizing real software isn’t about solving algorithmic puzzles: it’s about navigating a complex ecosystem where every change can have unpredictable ripple effects.

Consider the difference: In the Pie4Perf research, optimizing a sorting function is straightforward. In production, that same sorting function might be called by dozens of other services, each with different performance requirements, memory constraints, and failure modes. Change the sorting algorithm, and you might accidentally break a service that depends on the specific memory usage pattern of the original implementation.

The Verification Challenge: When “It Works” Isn’t Enough

Here’s where the story becomes truly interesting—where the gap between contest programming and production reality becomes a chasm. In competitive programming, success is binary: either your solution passes all test cases, or it doesn’t. In production systems, “it works” is merely the beginning.

As Amir explained, “The verification of the generated code was much more challenging compared to what we had in the research setting. For the research paper, it was unit tests. We tested with unit tests. That’s it. But for Google scale, you have to ensure that it does not create any problem down the line.”

To understand why this matters, consider renovating a single room in your house versus a room in a 50 story skyscraper. In your house, you mainly worry about that one room. But in the skyscraper, changing the plumbing in one apartment might affect water pressure throughout the building, structural modifications could impact the foundation, and electrical changes might overload circuits serving other floors.

This interconnectedness is a defining feature of google3,google3: Google’s third-generation monolithic repository layout that contains billions of lines of code across thousands of projects. Unlike most companies that use separate repositories for different projects, Google maintains nearly all their code in a single massive repository managed by Piper, their custom version control system. This approach enables unprecedented code sharing and dependency management but creates complex optimization challenges where changes in one area can affect seemingly unrelated systems across Google’s entire infrastructure. Google’s monolithic repository. “There’s a very connected codebase,” Amir noted. “So if you submit one code, even if it passes unit tests, it might create problems for different parts of the codebase.”

A seemingly innocent optimization—say, changing how a function handles memory allocation—could have cascading effects across dozens of services, potentially causing performance degradation in systems that seem completely unrelated.

ECO’s solution employs a sophisticated multi stage verification pipeline that makes traditional software testing look simple by comparison:

Stage 1: AI Quality Filter: Before any human ever sees an AI-generated optimization, it must pass through automated quality checks. “We created a system that filters some of these edits and ensures that the edits are high quality before going to the human,” Amir explained. Think of this as having a team of AI reviewers that can instantly spot obvious problems—like optimizations that break basic coding standards or introduce security vulnerabilities. This filtering prevents human developers from being constantly interrupted with obviously flawed suggestions.

Stage 2: Expert Human Review: Even after passing automated checks, every single change must be reviewed by a human developer—not just any developer, but specifically the person who originally wrote the code being optimized. “We have to make sure that the original developer of the code is going to review this change as well, because we don’t want to have additional context issues.” This is like requiring the original architect to approve any changes to a building’s structural elements.

Stage 3: Continuous Production Monitoring: The verification doesn’t stop once code goes live. “After that, even after that, we have to continuously check to monitor and make sure the edit makes sense. It doesn’t create any other bugs, any other issues.” ECO continuously monitors the performance impact of every optimization, ready to automatically roll back changes that cause unexpected problems.

This represents a fundamental paradigm shift. Competitive programming operates on “generate and test”: if it passes test cases, you’re done. Production systems require “generate, filter, review, deploy, monitor, and adapt”: a process that can take weeks or months for a single optimization.

The Classroom Question: Will AI Performance Agents Replace Everything?

During our class discussion, a student posed a provocative question: “Will AI performance agents eventually replace all human involvement in code optimization?” This question reflects broader anxieties in the software engineering community about job displacement and the future role of human developers in an AI-dominated landscape.

Amir’s response, reflecting the team’s philosophy, was illuminating and reassuring: “There is no way that we can remove the original code developer, because we still want to rely on high quality edits.” But this isn’t just about preserving jobs: it’s about fundamental technical limitations that emerge when deploying AI systems in heterogeneous, warehouse scale computing environments.Heterogeneous Computing Challenges: Modern data centers contain diverse processor architectures—Intel Xeon, AMD EPYC, ARM Graviton, NVIDIA GPUs, Google TPUs, and custom accelerators. Each architecture has different optimization sweet spots: what improves performance on Intel CPUs might degrade performance on ARM processors. This hardware diversity makes automated optimization exponentially more complex, as AI systems must understand not just code patterns but also how those patterns interact with specific silicon architectures across Google’s global fleet.

The answer reveals why complete automation remains elusive, particularly in warehouse scale systems where heterogeneous computing creates optimization challenges that no single AI system can fully comprehend. This touches on a core theme from Leiserson’s work: performance engineering requires understanding the full computing stack, from algorithms to architecture, making it difficult to automate fully:

The Context Problem: AI systems, no matter how sophisticated, lack the deep contextual understanding that human developers possess. The original code author knows why certain design decisions were made, what constraints the system operates under, and how the code fits into the broader business requirements. “We have to make sure that the original developer of the code is going to review this change as well, because we don’t want to have additional context issues,” Amir explained.

Consider this analogy: An AI might suggest replacing a wooden bridge with a steel one because steel is stronger and more durable. But the human engineer knows the wooden bridge was chosen because it’s in a historic district where steel structures are prohibited, or because the soil conditions can’t support the additional weight of steel.

The Complexity Trade-off: Beyond correctness, human developers must evaluate whether optimizations are worth their cost in complexity. “Sometimes the developer is going to look at the code, they said, ‘Oh, it’s correct. It gives some performance improvement, but in terms of the complexity that it adds to the code, it’s not a useful change that we should submit,’” Amir noted.

This reflects a fundamental truth about software engineering: the “best” solution isn’t always the fastest one. Sometimes a 10% performance improvement isn’t worth making the code 50% harder to understand and maintain.

The Responsibility Factor: When something goes wrong in production, it’s not the AI that gets called at 3 AM to fix it: it’s the human developer. This accountability creates a natural incentive for careful review that no automated system can replicate.

Student Questions: The Future of AI Code Optimization

The class discussion raised several thought-provoking questions that highlight the fundamental challenges and opportunities in AI-assisted performance engineering:

The Reward Hacking Problem: Students raised concerns about AI systems “gaming” their optimization metrics by exploiting loopholes in test suites. This isn’t theoretical—real AI systems have been observed bypassing unit tests through clever but incorrect optimizations that technically pass all checks. The solution requires moving beyond simple unit tests to incorporate formal verification methods that can mathematically prove correctness, not just test it empirically. This challenge becomes even more complex at production scale, where the cost of subtle errors can be enormous.

The Watermarking Question: As AI-generated code becomes more prevalent, the question of attribution and detection becomes crucial. How do we distinguish between human-written and AI-generated code? This matters not just for academic integrity in educational settings, but also for liability, debugging, and maintenance in production systems. While some organizations mark AI-generated code explicitly, this practice isn’t universal, raising questions about transparency and accountability in AI-assisted development.

The Coverage Challenge: A particularly insightful student observation highlighted that AI systems might modify code paths that lack comprehensive test coverage. This creates a dangerous blind spot—the AI could introduce bugs in untested code that wouldn’t be caught until production. The challenge extends beyond just having tests; it requires ensuring that AI systems understand and respect the boundaries of what has been properly validated versus what remains untested territory.

The Complexity Trade-off: Perhaps the most philosophical question raised was whether code readability and simplicity still matter if AI can explain and maintain arbitrarily complex code. This touches on a fundamental tension in software engineering: should we optimize for human understanding or machine efficiency? The reality is more nuanced—even AI systems struggle with overly complex code in future iterations, suggesting that clarity benefits both humans and machines. In critical systems where human oversight remains essential, maintaining comprehensible code isn’t just nice-to-have—it’s a safety requirement.

ECO’s Production Reality: The Numbers and Challenges

The ECO team’s results illuminate both the successes and limitations of production AI code optimization at unprecedented scale. Over one year, the system made 6,400 commits that reached production, consisting of over 25,000 lines of code changes across Google’s billions of lines of code. Remarkably, less than 0.5% of these commits were rolled back, demonstrating the effectiveness of the multi stage verification pipeline they developed. Most impressively, these optimizations resulted in performance savings equivalent to over 500,000 normalized CPU cores per quarter—a massive efficiency gain that translates to significant cost and energy savings across Google’s global fleet.

However, the path to these successful commits reveals the complexity of production deployment. ECO’s commits fall into several categories:

-

Direct Production: Code that gets directly added to production after passing all verification stages

-

Human Modified: Code that reviewers saw as good optimization targets but required human editing before production

-

Validation Rejected: A significant portion rejected during the automated validation phase, “saving a lot of human resources in reviewing”

-

Human Rejected: A substantial number rejected by human reviewers even after passing automated validation

This breakdown reveals that success in production AI code optimization isn’t just about generating good code—it’s about building systems that can filter, adapt, and integrate AI suggestions into complex human workflows.

The Infrastructure Reality: ECO builds on decades of infrastructure investment that Google has made in telemetry and monitoring systems. This foundation of existing infrastructure—built by countless teams over many years—is what makes large-scale AI code optimization possible.

This infrastructure dependency explains why we see “iconic demos from Google and Meta and so forth, and then you won’t hear anything from anybody else, because you don’t have the infrastructure.”

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: From FORTRAN to AI

To truly appreciate the significance of ECO’s achievements and the challenges it faces, we need to understand the long history of performance optimization that preceded it.

Performance optimization has always been important, but its nature has evolved dramatically over seven decades of computing history:

A Blast from the Past: The FORTRAN I compiler (1957) pioneered many optimization techniques we still use today: constant folding, common subexpression elimination, and strength reduction. John Backus’s team spent 18 person years developing it, with most effort going into the optimizer. Their goal was to generate code within 2x of hand written assembly: a target that took years to achieve but revolutionized computing when they did.

The Classical Era (1950s-1980s): Early FORTRAN and COBOL compilers focused on making high-level languages practical. The challenge was fundamental—could compiled code ever match hand-optimized assembly? Pioneers like Frances Allen at IBM developed the theoretical foundations of dataflow analysis and control flow graphs that underpin all modern optimizers. These early systems targeted scientific computing workloads where every CPU cycle mattered for weather simulations, nuclear calculations, and aerospace engineering.

The RISC Revolution (1980s-1990s): The Reduced Instruction Set Computing movement changed optimization priorities. Compilers became responsible for instruction scheduling, register allocation, and exploiting instruction-level parallelism. The Stanford MIPS compiler and IBM’s RISC System/6000 optimizer showed that simple hardware plus smart compilers could outperform complex CISC designs.

The Multicore Transition (2000s-2010s): When single-thread performance plateaued, optimization shifted toward parallelization. OpenMP, Intel’s Threading Building Blocks, and automatic parallelization tools tried to help developers exploit multiple cores. But Amdahl’s Law proved harsh—many algorithms resist parallelization, and synchronization overhead often ate the gains.

The Specialized Hardware Era (2010s-Present): With GPUs, TPUs, and custom accelerators, optimization became about matching computation patterns to hardware capabilities. This isn’t just about making code faster—it’s about recognizing which parts of an algorithm map well to vector units, tensor cores, or systolic arrays. This era embodies Leiserson’s vision of hardware software co-design, where optimal performance requires understanding both algorithmic structure and underlying silicon architecture.

Legacy Code Reality: Estimates suggest 200+ billion lines of COBOL still run in production, processing 80% of daily business transactions. Much of the world’s critical infrastructure—banking, insurance, government systems—depends on FORTRAN and COBOL code written decades ago. These systems can’t be rewritten from scratch, making automated optimization tools essential for modernization without disruption.

The AI Assisted Future (Present-?): What makes today different isn’t just that we’re using AI for optimization—it’s that we’re approaching fundamental limits of traditional techniques. Modern compilers already implement hundreds of optimization passes, but they’re hitting diminishing returns. AI offers something new: the ability to learn optimization patterns from millions of examples, understand high-level intent, and make optimization decisions that consider the entire system context, not just local code patterns.

This represents the next evolution in Leiserson’s performance engineering vision. Where traditional approaches focused on cache aware algorithms and vectorization within fixed compiler frameworks, AI assisted optimization can potentially discover novel optimization strategies that human performance engineers never considered, while simultaneously handling the complexity of modern heterogeneous hardware environments.

Why Traditional Approaches Are Hitting Their Limits

Given this rich history of compiler optimization, one might wonder why we need AI assistance at all. The answer lies in fundamental limitations that traditional approaches can’t overcome:

Traditional compiler optimization faces several fundamental challenges that AI might address:

The Phase-Ordering Problem: Compilers apply optimizations in sequence, but the optimal order depends on the specific code. Should you inline functions before or after loop optimization? There’s no universal answer, and trying all permutations is computationally infeasible.

The Prediction Problem: Many optimizations require predicting runtime behavior—which branches are likely taken, which functions are hot, which data will be in cache. Static analysis can only go so far; real workloads often behave differently than compilers expect. This exemplifies Leiserson’s emphasis on cache aware algorithms: understanding memory hierarchy behavior is crucial for performance but difficult to predict statically.

The Context Problem: Traditional optimizers see only local context. They can’t know that optimizing one function might pessimize its callers, or that a “slow” algorithm might be better because it has more predictable memory access patterns. Leiserson’s work on cache oblivious algorithms showed how algorithmic design must consider the entire memory hierarchy, not just CPU operations.

The Hardware Diversity Problem: Modern datacenters contain heterogeneous hardware—Intel CPUs, AMD CPUs, ARM processors, various GPU generations, custom accelerators. Optimizing for one architecture often pessimizes others. As Amir noted, even within x86, optimal code for Intel and AMD processors can differ significantly.Warehouse-Scale Heterogeneity: Google’s infrastructure spans thousands of data centers globally, each containing different generations of hardware deployed over decades. A single service might run across machines with Intel Haswell CPUs (2013), AMD Milan processors (2021), custom TPU v4 chips, and various GPU accelerators. Code optimized for one generation’s cache hierarchy or instruction set might perform poorly on others, requiring AI systems to understand not just algorithmic optimization but also hardware-specific microarchitectural details across this diverse ecosystem.

This is where AI assisted optimization becomes genuinely transformative. While traditional compilers operate on syntactic patterns and fixed heuristics, AI systems can potentially understand semantic relationships, learn from vast codebases, and make optimization decisions that consider factors no traditional compiler could access. They can learn which optimizations work for specific applications, adapt to actual runtime behavior, and even discover novel optimization strategies that human compiler writers never considered.

In Leiserson’s terminology, AI assisted optimization represents a new frontier in performance engineering—one that can simultaneously consider algorithmic improvements, parallelization opportunities, and hardware-specific optimizations like vectorization. Where traditional approaches required manual expertise in each domain, AI systems might learn to navigate the entire optimization space automatically.

The Academic Imperative: Shining Light on What’s Possible

Having explored the historical context and current limitations, we turn to a crucial question from our class discussion: What is academia’s role in this rapidly evolving landscape?

The class discussion revealed a fundamental tension: while companies like Google focus on making their current systems more reliable and efficient, academia’s role is different. Our job isn’t to solve today’s problems but rather to illuminate the problems and opportunities that companies should be thinking about five to ten years from now.

This aligns perfectly with Leiserson’s call for a renewed focus on performance engineering as a discipline. He argued that computer science education had shifted too far toward abstraction and theory, neglecting the practical skills needed to extract performance from modern hardware. Academic research in AI assisted optimization represents exactly the kind of performance engineering discipline Leiserson advocated: combining algorithmic innovation with deep understanding of hardware capabilities.

This distinction became clear when students questioned academia’s role in a landscape dominated by companies with massive infrastructure advantages. The answer isn’t to compete with Google’s scale but to explore the fundamental questions that scale can’t answer:

Understanding Optimization Limits: One student highlighted the need to understand “what is the most optimal a piece of code can get,” noting that modern systems often operate far from theoretical performance bounds. This is a fundamental research question that academia is uniquely positioned to address, not because we have better infrastructure, but because we can afford to ask questions that don’t have immediate commercial value.

This directly addresses Leiserson’s central thesis: there remains enormous “room at the top” between current software performance and theoretical hardware limits. Academic research can quantify this gap, develop methodologies for measuring it, and create frameworks for systematically closing it—work that has long-term value beyond immediate commercial applications.

Democratizing Optimization: Perhaps most importantly, students questioned whether the focus should shift from replicating Google-scale infrastructure to solving problems for organizations without such resources. As one student put it: “Don’t you feel like this is a capitalism question, and our attention should be on critical [systems]… there’s a ton of code that people are not editing.”

This perspective highlights academia’s unique opportunity: while industry focuses on optimizing high value, well maintained codebases, vast amounts of critical software (from scientific computing to infrastructure systems) remain unoptimized simply because they lack the economic incentives that drive commercial optimization efforts.

Papers That Shaped Our Discussion

To provide proper context for our exploration, we should examine the foundational research that informed both our discussion and the development of systems like ECO:

This week’s exploration drew from several key sources that illuminate the production reality of AI code optimization:

-

“Learning Performance-Improving Code Edits” - A collaborative research effort by a team from University of Pennsylvania, Carnegie Mellon University, Google, and Google DeepMind, published at ICLR 2024. This work demonstrated the feasibility of using LLMs for code optimization in controlled settings, achieving up to 9.64x speedup with their best model and serving as the foundational research that enabled ECO’s warehouse-scale deployment.

-

“ECO: An LLM-Driven Efficient Code Optimizer for Warehouse-Scale Computers” - A large-scale collaborative effort from Google and Google DeepMind. The paper reveals the infrastructure complexity required to move from research prototypes to systems that optimize billions of lines of code, achieving over 25k lines of production code changes across 6.4k commits with >99.5% success rate.

-

“Google-Wide Profiling: A Continuous Profiling Infrastructure for Data Centers” - The foundational infrastructure paper that enabled ECO’s success, demonstrating how decades of telemetry investment creates the foundation for AI-assisted optimization at warehouse scale.

-

“There’s Plenty of Room at the Top: What Will Drive Computer Performance After Moore’s Law?” - Charles Leiserson’s influential 2010 paper that anticipated the end of automatic performance scaling and called for renewed focus on performance engineering as a discipline. The paper identified three key opportunities for continued performance improvement: algorithmic advances, better parallelization, and hardware-software co-design—themes that directly inform today’s AI-assisted optimization efforts.

The Infrastructure Reality: What We Learned

The presentation crystallized a fundamental insight: the gap between research demonstrations and production deployment isn’t just about scale—it’s about entirely different problem formulations. Pie4Perf’s success in controlled settings doesn’t automatically translate to ECO’s warehouse-scale challenges because production systems require infrastructure that research environments never need.

The key infrastructure requirements that emerged from our discussion:

Verification Pipelines: Moving beyond unit tests to comprehensive validation that includes formal verification, system-wide impact analysis, and continuous monitoring.

Human-AI Collaboration Systems: Tools that preserve human agency and understanding while leveraging AI capabilities, ensuring that developers remain in control of critical decisions.

Context Management: Infrastructure that helps AI systems understand system-wide dependencies and helps humans verify the implications of AI-generated changes.

Organizational Adaptation: Processes that integrate AI assistance into existing development workflows without disrupting the human expertise that remains essential.

Looking Ahead: From Research to Practice

Next week, we’ll continue exploring the practical realities of AI-assisted performance engineering with insights from Sasha Rush and the team at Cursor, who are building AI-powered development tools used by millions of developers worldwide. Their perspective on deploying AI assistance in real development workflows will provide another crucial data point in understanding how to bridge the gap between research capabilities and production utility.

The lessons from this week—the importance of verification infrastructure, the necessity of human-in-the-loop systems, the reality that production deployment requires entirely different approaches than research prototypes—will provide a foundation for understanding how companies like Cursor are tackling these challenges in practice. As we continue our journey through AI-assisted design, we’ll see how these fundamental insights apply across different scales and contexts.

🎯 Key Takeaways

- Scale Changes Everything: Moving from Pie4Perf's controlled environment to ECO's production scale required solving entirely different classes of problems

- Verification is Infrastructure: Production AI code optimization requires extensive validation pipelines that dwarf the complexity of research settings

- Human Expertise Remains Essential: Even sophisticated AI systems require human developers for context, quality assessment, and final decision-making

- Infrastructure Dependency: Success stories like ECO build on decades of telemetry and tooling investment that most organizations lack

- Academic Opportunity: Universities can focus on fundamental questions about optimization limits and democratizing AI assistance beyond large-scale infrastructure

- Non-Determinism as Feature: Controlled randomness in AI optimization can discover solutions that purely deterministic approaches miss

The journey from competitive programming victories to production code optimization reveals a broader truth about AI-assisted engineering: we’re still at the very beginning. The technical capabilities demonstrated in research settings are just the first step in a much longer journey toward truly intelligent systems that can collaborate with humans to build better software.

Questions for the Road Ahead

As we stand at this inflection point, several fundamental questions emerge that will shape the future of AI-assisted performance engineering:

For Researchers: How do we develop AI optimization systems that work without Google-scale infrastructure? Can we create lightweight, generalizable approaches that benefit the long tail of software projects that lack commercial optimization incentives?

For Practitioners: As AI agents become more capable, how do we maintain the human expertise needed to understand and debug the systems we’re responsible for? What new skills will developers need in a world where AI handles routine optimizations?

For Society: If AI-assisted optimization remains concentrated among a few large companies, what are the implications for software equity? How do we ensure that critical infrastructure, scientific computing, and open-source projects benefit from these advances?

For the Field: How do we balance the pursuit of autonomous AI agents with the need for human understanding and control? What verification and safety mechanisms will we need as these systems become more powerful and widespread?

The answers to these questions will determine whether AI-assisted performance engineering becomes a transformative force for all of computing or remains a competitive advantage for a select few. The choice is ours to make.

Note: The views expressed by our guest speaker are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer.

For detailed readings, slides, and materials for this week, see Week 4 in the course schedule.