Week 3: Can AI Really Replace Software Engineers? The Reality Behind Contest-Winning Code

As we were teaching class this very Wednesday, September 17th, news broke that Google DeepMind’s Gemini achieved gold medal level performance at the 2025 International Collegiate Programming Contest (ICPC) World Finals, solving 10 of 12 complex algorithmic problems in the world’s most prestigious competitive programming competition.Gemini’s ICPC performance builds on its IMO gold medal just two months earlier. The system used multiple agents proposing solutions, executing code in terminals, and iterating based on feedback. Exactly the kind of sophisticated approach that works for isolated problems. The achievement represents a “profound leap in abstract problem solving,” according to DeepMind. Dr. Bill Poucher, ICPC Global Executive Director, proclaimed: “Gemini successfully joining this arena, and achieving gold level results, marks a key moment in defining the AI tools and academic standards needed for the next generation.”

Yet here’s the fascinating challenge we explored in class: these same models that can win gold medals in competitive programming contests face dramatically different obstacles when applied to real production code. This week, we dove deep into understanding this gap and what it reveals about the fundamental differences between solving algorithmic puzzles and building maintainable, efficient software systems.

🔑 Key Takeaways

- The Reality Gap: Contest-winning AI excels at isolated problems but encounters significant challenges when applied to real software engineering tasks

- Context is Everything: Real software engineering requires understanding system architecture, technical debt, and evolving requirements that competitive programming never tests

- The Localization Crisis: Models consistently optimize wrong functions, missing critical performance bottlenecks in production systems

- Benchmark Overfitting: We're celebrating victories in domains fundamentally different from the problems we actually need to solve

In 1988, Geoffrey Fox and Jeff Koller had a vision.Geoffrey Fox is now the working group chair of MLPerf Science at ML Commons. I’ve had the privilege of collaborating with him on MLPerf for Science benchmarks, bringing his 1988 vision full circle to modern AI evaluation. They envisioned neural networks that could understand and improve real software systems, not just solve algorithmic puzzles, but tackle the messy, interconnected challenges of building and maintaining production code. Their dream was about bridging the gap between artificial intelligence and the complex reality of software engineering.

Their ambitious vision proved to be ahead of its time. Neural networks capable of understanding complex software systems, architectural patterns, and engineering trade-offs were still decades away from being practical.

Fast forward 35 years. We now have the neural networks Fox and Koller could only dream of. Large language models that can write poetry, prove theorems, and yes, even win gold medals in competitive programming contests. The International Olympiad in Informatics? Solved. AtCoder competitions? Dominated.

So surely we’ve achieved their vision of intelligent software engineering, right?

The answer reveals a more complex story than these competitive programming victories might suggest.

The Software Engineering Paradox

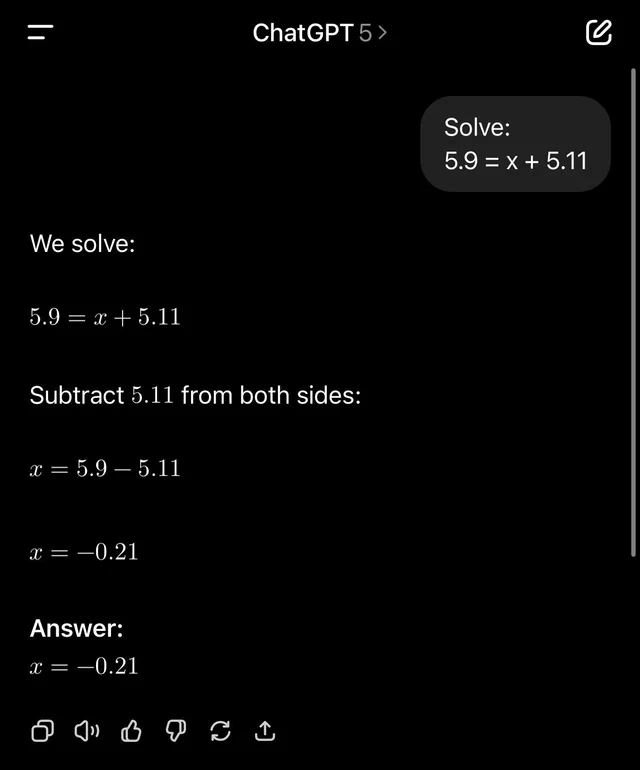

The same models that excel at competitive programming encounter substantial challenges when applied to real software engineering tasks. This mirrors the well-known phenomenon where ChatGPT can perform complex reasoning tasks yet struggles with seemingly simple decimal number comparisons.

This represents a significant research challenge that reveals important insights about the difference between solving clean, well-defined problems and working with the complex reality of software engineering.

Here’s what nobody tells you about these impressive competitive programming results: they’re solving a completely different problem than what Fox and Koller were trying to tackle. Consider Gemini’s approach to the unsolved Problem C: it “assumed each reservoir has a ‘priority value’” and used “nested ternary searches to quickly find optimal priority values in the bowl-like convex solution space.” This is exactly the kind of mathematical elegance that works for isolated problems with perfect specifications and deterministic verification.

Real software engineering requires understanding legacy systems, navigating technical debt, making architectural tradeoffs, and reasoning about maintainability in environments where everything is interconnected and constantly evolving. There are no “bowl like convex solution spaces” when you’re debugging a memory leak in a distributed system built by five different teams over three years.

The Context Problem

Recent benchmarking work has revealed important insights about current limitations. When researchers tested modern LLMs on real software engineering tasks, from performance improvements to architecture refactoring, they discovered that many challenges stem from a fundamental source: lack of system context. The models tend to focus on isolated code fragments while missing the broader architectural patterns and engineering constraints.

Think about what this means. These aren’t subtle mistakes in implementation details, but rather fundamental gaps in understanding how software systems actually work. The models might spend enormous effort refactoring a rarely used utility function while missing critical architectural considerations that affect the entire system’s maintainability and scalability.

This context problem exposes a deeper issue. Software engineering requires understanding system architecture, recognizing design patterns, managing technical debt, and making tradeoffs between performance, maintainability, and development velocity—a kind of systems thinking that competitive programming simply doesn’t test.

The benchmark data reveals an important research challenge: while human experts can identify engineering opportunities ranging from architectural improvements to maintainability gains, language models currently struggle with comprehensive system understanding. They may introduce correctness issues, focus on surface level metrics, and miss the broader engineering characteristics of real systems.

The Evolution from AlphaCode

Remember AlphaCode’s breakthrough in 2022? The key insight was generating millions of candidate solutions and filtering them down to the best ones.Gemini’s 2025 ICPC approach evolved from AlphaCode’s strategy but added multi-agent collaboration and iterative refinement. Still fundamentally a generate-and-test paradigm, just more sophisticated. DeepMind framed this as “creativity,” but it’s more accurately understood as extremely sophisticated computational search.

The approach worked because competitive programming problems have a specific structure. You can generate lots of solutions, test them against known inputs, and pick the ones that work. But real software engineering doesn’t have this luxury. There’s no simple test that tells you whether your architectural decision is correct, and there’s certainly no way to generate millions of design variants and pick the best one.

Current approaches have doubled down on this test time compute scaling. If one million samples worked, surely ten million will work better. But we’re hitting the limits of what pure computational power can solve. The fundamental problem isn’t that we need more samples. It’s that we’re sampling from the wrong problem space.

The Jagged Frontier

One of the most fascinating discussions in class centered on what we’re calling the “jagged frontier” of AI capabilities. These models can solve International Mathematical Olympiad problems that stump PhD mathematicians, but they fail at basic arithmetic when the numbers get large enough. They can write elegant recursive algorithms but can’t figure out why a simple loop is running slowly.

This raises a provocative question in our class discussion: Is human difficulty the right metric for machine difficulty? We’ve been assuming that problems hard for humans will be hard for machines, but the evidence suggests otherwise. Competitive programming platforms like CodeChef and HackerRank might be “easy” for AI precisely because they don’t require the kind of messy, contextual reasoning that humans struggle with—which means we might be celebrating victories in domains fundamentally different from the problems we ultimately need to solve.

The SWE-Bench Reality Check

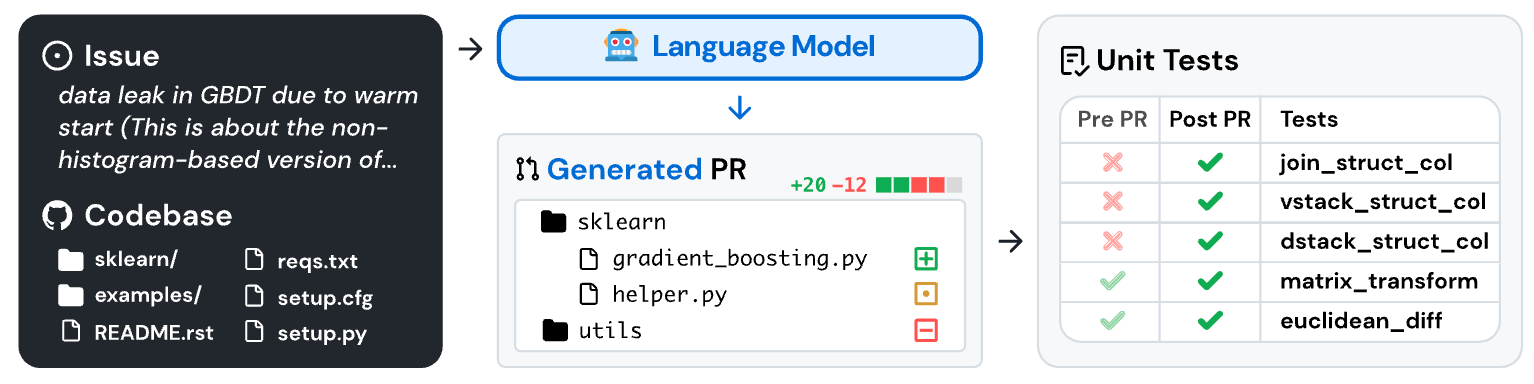

This brings us to one of the most important developments in software engineering benchmarking: SWE-Bench, pioneered by Ofir Press at Princeton University.Ofir Press is a Princeton postdoctoral researcher who earned his PhD from the University of Washington. He’s focused on large language models for code and evaluation, and served as our guest speaker for this week’s class. As Ofir explained in his recent talk to our class, SWE-Bench represents a fundamental shift in how we evaluate AI systems on real software engineering tasks.

SWE-Bench is a benchmark that uses actual GitHub issues and pull requests from real repositories as question-answer pairs, testing whether AI models can fix bugs and develop features in real-world codebases. Unlike synthetic coding problems with clean specifications, SWE-Bench presents models with the messy reality of production software: incomplete bug reports, legacy code dependencies, and the need to understand complex system interactions.

The results provide important insights. Even state-of-the-art models face significant challenges with these real-world software engineering tasks. But Ofir’s insights go deeper than just performance numbers. He highlighted a critical issue that affects our entire field: benchmark overfitting. As he put it, “developers focus on scoring well rather than overall programming.” This creates a risk of optimizing for metrics that may not translate directly to real-world engineering success.

The SWE-Bench approach addresses three fundamental requirements that Ofir emphasized: benchmarks must be challenging, verifiable, and useful. Traditional competitive programming benchmarks like Codeforces and LeetCode fail the “useful” test because they measure capabilities that don’t transfer to real software engineering. SWE-Bench tests AI models’ ability to understand codebases, navigate technical debt, and implement changes that don’t break existing functionality.

Even with this more realistic benchmark, current AI systems face challenges with what Ofir calls the “software engineering fundamentals.” They can generate syntactically correct code, but they encounter difficulties with system-level reasoning, understanding architectural constraints, and making the kind of engineering trade-offs that experienced developers handle instinctively. This motivates our exploration of Google’s ECO (Efficient Code Optimization) system next week—to understand what we actually observe in real large-scale systems.

The Missing Link

The gap between competitive programming success and real engineering challenges reveals something crucial about the nature of software development. Competitive programming problems are isolated puzzles. Real code exists in complex ecosystems.

When you’re building production software, you’re reasoning about code that was written by dozens of different people over years, with dependencies on libraries you’ve never seen and assumptions that were never documented. You’re considering system architecture, deployment constraints, monitoring requirements, security considerations, team collaboration patterns, and countless other factors that interact in unpredictable ways.

This is why the context problem is so revealing. Models need to develop better understanding of how to think about software systems as interconnected wholes, moving beyond the pattern matching that succeeds in competitive programming toward the fundamentally different reasoning that software engineering requires.

What Real Progress Would Look Like

So what would it actually mean to achieve Fox and Koller’s vision? It would mean having systems that can look at a codebase and understand not just what each function does, but how the entire system behaves under different conditions. It would mean recognizing that the bottleneck isn’t always in the code you’re looking at, but might be in how that code interacts with the database, the deployment infrastructure, or the team’s development workflow.

Real progress would mean moving beyond the generate-and-test paradigm that works for competitive programming. It would require models that can reason about system behavior, understand engineering trade-offs, and make the kind of holistic judgments that human experts make when they architect maintainable systems.

The Code Representation Challenge

Before diving into Ofir’s agent innovations, we need to address a fundamental question: How should AI systems understand code? This question sits at the heart of why we selected Code2Vec as one of our key readings this week. Code2Vec represents a fascinating middle ground between two extremes: purely data driven methods (like modern LLMs) and traditional compiler approaches that rely on formal program analysis.

Code2Vec treats code as abstract syntax trees (ASTs) rather than sequences of tokens, much like how traditional compilers parse programs. It learns distributed representations by analyzing the structural paths between AST nodes, capturing semantic relationships that pure text based models might miss. When Code2Vec looks at a function, it doesn’t just see a string of characters; it understands the syntactic relationships, control flow, and semantic structure that compilers have used for decades.

This hybrid approach raises a provocative question we explored in class: Are we limiting AI’s understanding of code by forcing it through the lens of natural language? Current approaches like CodeBERT and Code Llama treat code as text, applying the same tokenization and attention mechanisms used for human language. But code has structure that text doesn’t: formal semantics, execution behavior, and compositional properties that traditional compiler analysis captures but text based models struggle with.

The tension between structural and textual representations reflects a deeper philosophical divide in how we think about code understanding. Should AI systems learn to “read” code the way humans do, or should they leverage the structured representations that compilers have perfected? Perhaps the future lies in what we might call “compiler inspired neural networks” that fuse the best of both worlds: the pattern recognition power of deep learning with the formal rigor of program analysis.

The Agent Interface Innovation

Ofir’s work on SWE-Agent reveals another crucial insight: the importance of agent-computer interfaces. As he explained, “good agent computer interfaces are similar to how humans need good graphical user interfaces.” Traditional approaches to AI coding simply feed raw code to language models, but SWE-Agent introduces custom commands designed specifically for software engineering tasks: open, search, edit, and submit.

This interface design addresses a fundamental problem that emerged from SWE-Bench evaluation: models often fail not because they can’t generate good code, but because they can’t navigate large codebases effectively. They get lost in the complexity, make changes in the wrong files, or introduce bugs because they lack proper context about the system they’re modifying. This echoes challenges seen in tools like GitHub Copilot and CodeT5 when applied to large-scale software projects.

The results speak volumes. SWE-Agent, which started as a 100-line implementation, achieved significant improvements on SWE-Bench simply by providing better ways for AI models to interact with code. This isn’t just an engineering trick—it reveals that the bottleneck in AI software engineering might not be the models themselves, but how we design their interaction with complex software systems.

The Overfitting Problem

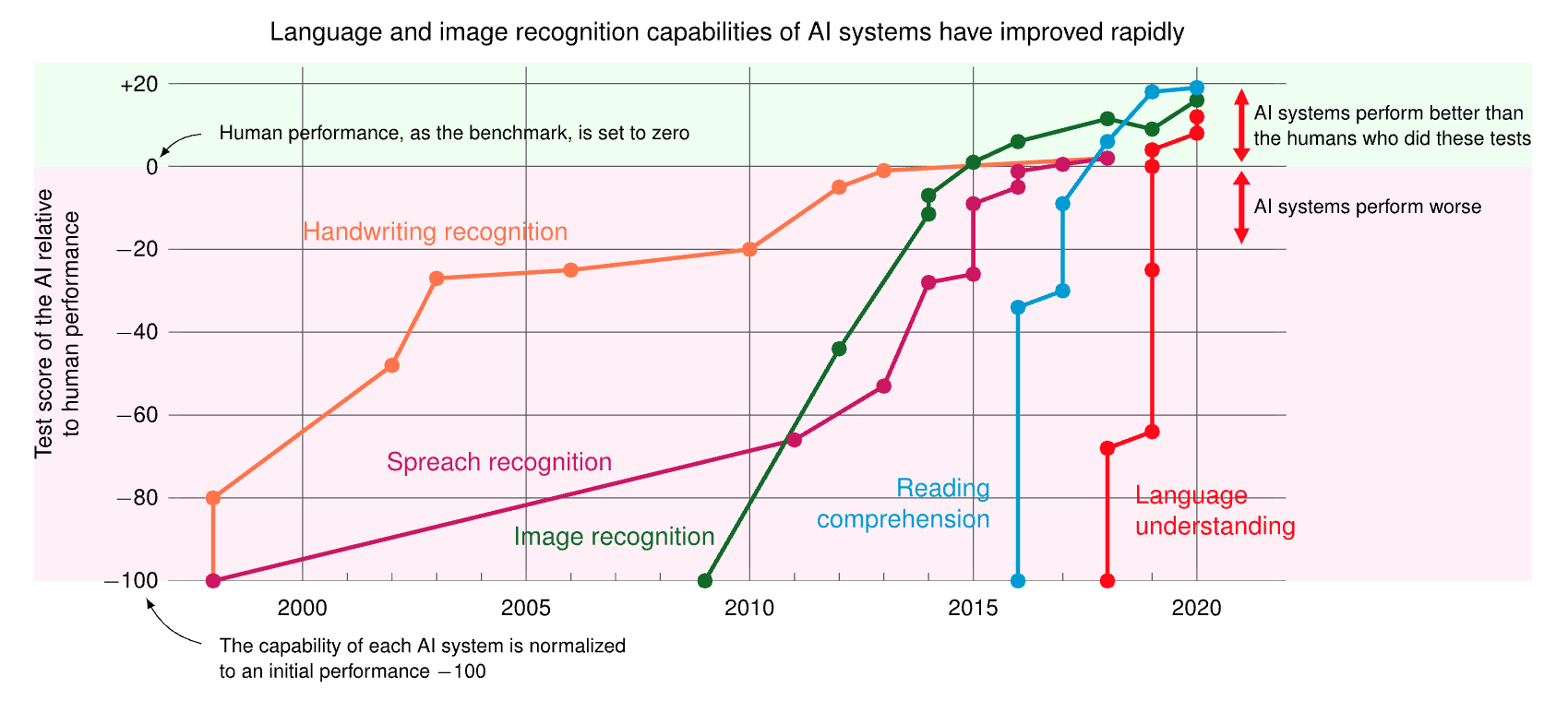

But Ofir’s most important insight concerns the broader evaluation landscape. As he put it, we’re seeing massive “benchmark overfitting”—where developers focus on scoring well on specific metrics rather than building systems that solve real problems. This creates what he calls a “saturation” problem: as AI systems get better at existing benchmarks, the benchmarks themselves become less useful for driving real progress. The figure illustrates this trend, showing AI systems surpassing human performance across various application benchmarks over the past decade.

The metrics that make us feel good about AI progress in programming—the competitive programming victories and the algorithmic puzzle solving—might be measuring capabilities that are orthogonal to what we actually need. When you can generate millions of candidate solutions and filter them down using known test cases, you’re solving a fundamentally different problem than understanding why a production system is hard to maintain.

This creates a dangerous illusion of progress. We celebrate superhuman performance on clean, well-defined problems while ignoring the massive gap in messy, real-world scenarios where context matters more than algorithmic creativity. DeepMind boldly claims that these achievements show “AI is moving from just processing information to actually helping solve some of the world’s most difficult reasoning problems in ways that could benefit humanity.” Yet Ofir emphasized that the field needs “continuous innovation in benchmarks to keep up with AI advancements”—we need benchmarks that evolve as quickly as the models we’re testing, and more importantly, that actually measure the capabilities we need for real world impact.

Academia’s Critical Role in Benchmarking

One of the most important discussions we had in class centered on academia’s unique role in this rapidly evolving landscape. When benchmarks get saturated as quickly as they do today, what can universities contribute that industry cannot?

The answer lies in academia’s unique position and incentives. Industry naturally optimizes for immediate business value, which often means focusing on benchmarks that correlate with product success. But academia can take longer-term views, creating benchmarks that push the field toward fundamental capabilities rather than just commercial metrics.

SWE-Bench itself exemplifies this perfectly. Ofir’s work at Princeton created a benchmark that industry has now adopted widely, but it required the kind of sustained, fundamental research that academic environments enable. Similarly, the MLPerf benchmarks emerged from academic institutions like Harvard and Stanford through ML Commons, with tight industry collaboration, but with the academic freedom to focus on scientific rigor over immediate commercial applicability.This academic-industry collaboration model will be crucial as we move beyond software to tackle AI for architecture and chip design—the next phases of our course where the stakes and complexity multiply exponentially.

This academic-industry collaboration model seems crucial for the future of AI evaluation. Universities can provide the intellectual independence and long-term perspective needed to create benchmarks that actually advance the field, while industry provides the scale, resources, and real-world validation needed to make these benchmarks meaningful.

The Path Forward

We’re at an important inflection point. We have neural networks powerful enough to begin tackling the problems Fox and Koller envisioned, but we need to ensure we’re applying them to the right challenges. The path forward likely involves more than just additional compute or bigger models trained on more competitive programming data.

The path forward requires new abstractions: benchmarks that test systems reasoning rather than just algorithmic reasoning, models trained on real engineering data rather than clean algorithmic puzzles, and evaluation metrics that capture the messy, interconnected nature of real software engineering problems. Recent work like BigCode and CodeBERT represents steps in this direction, but we’re still working toward Fox and Koller’s vision.

Most importantly, we need to be clear about what we’re actually solving. Competitive programming success is impressive, but it represents different challenges than software engineering. Bridging that gap remains a key research frontier for realizing Fox and Koller’s 35-year-old vision.

🎯 Key Takeaways

- The 35-year gap: Neural software engineering was envisioned in 1988 but remains unsolved despite having the neural networks to do it

- Code representation matters: The tension between structural (Code2Vec) and textual (LLM) approaches reveals fundamental questions about how AI should understand code

- SWE-Bench reveals the gap: Real-world GitHub issues expose significant differences between contest performance and engineering capability

- Interface innovation: SWE-Agent shows that agent-computer interfaces are as critical as the models themselves for software engineering tasks

- Academic-industry synergy: Universities provide the independence to create benchmarks that advance fundamental capabilities, while industry provides scale and validation

- Benchmark evolution imperative: We need benchmarks that evolve as quickly as AI capabilities to avoid saturation and maintain meaningful evaluation

The research opportunity ahead? We’re still working toward solving the problem that Fox and Koller posed 35 years ago. The tools have evolved dramatically, but the fundamental challenge remains fascinating: teaching machines to understand not just code, but the complex software systems in which that code lives and breathes.

For detailed readings, slides, and materials for this week, see Week 3 in the course schedule.