Week 2: The Fundamental Challenges Nobody Talks About

Here’s what nobody tells you about applying AI to computer architecture: it’s not just harder than other domains. It’s fundamentally different in ways that make most AI success stories irrelevant. This week, we confronted why the techniques that conquered vision, language, and games stumble when faced with cache hierarchies and instruction pipelines. Through examining Amir Yazdanbakhsh’s work on design abstractions and our deep dive into the five critical challenges facing our field, we discovered that the obstacles are both more subtle and more fundamental than they initially appear.

🔑 Key Takeaways

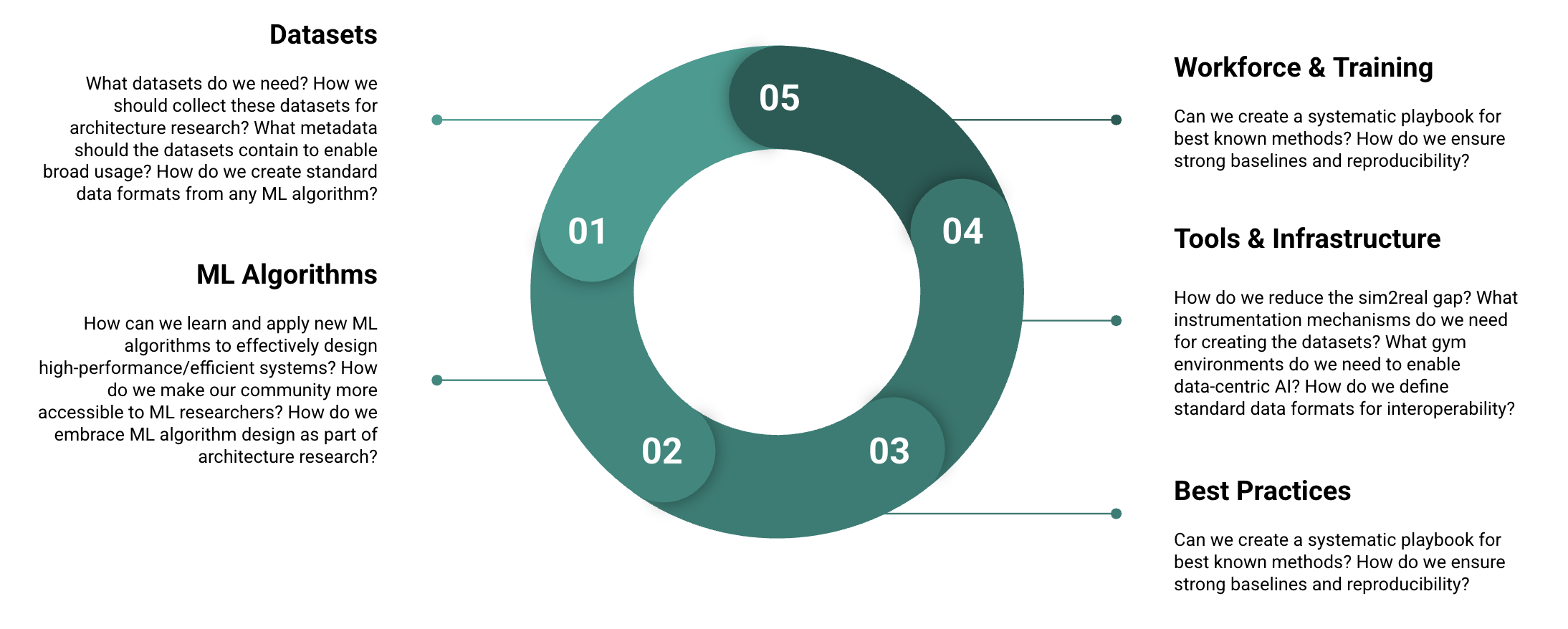

- Five Core Challenges: Dataset crisis, algorithm evolution treadmill, tools infrastructure gap, reproducibility crisis, and real-world robustness requirements

- Data is Different: Unlike other AI domains, we must deliberately create every training example through expensive simulation or hardware measurement

- Cascade Effect: These challenges compound each other, creating feedback loops that have kept Architecture 2.0 perpetually "five years away"

- Abstraction Rethinking: Traditional human-designed abstractions may limit AI agents' ability to discover truly novel cross-layer optimizations

The Five Fundamental Challenges

Our exploration revealed five interconnected challenges that make Architecture 2.0 uniquely difficult. Unlike other AI success stories, we can’t simply apply existing techniques and expect transformative results. Each challenge compounds the others, creating a complex web of technical and practical obstacles.

Challenge 1: The Dataset Crisis

The ImageNet comparison reveals the depth of our data problem. ImageNet succeeded because millions of people naturally generated and uploaded labeled images.ImageNet’s success built on the natural photo-sharing ecosystem of Flickr and other platforms. The ImageNet project cleverly leveraged human-generated content at scale—a luxury we don’t have in computer architecture where every data point requires expensive simulation. The data already existed; researchers just had to curate it. In computer architecture, no such natural data generation occurs. We must deliberately create every training example through expensive simulation or hardware measurement.

But the challenge goes deeper than availability. In computer vision, mislabeling a few cat photos as dogs barely affects overall classifier performance. In architecture, a single incorrect power measurement or wrong performance counter can derail an entire optimization trajectory. Data quality isn’t just important; it’s existential.

The simulation bottleneck makes everything worse. Generating training data means running cycle-accurate simulations that can take hours or days for meaningful workloads. We’re constantly trapped between fast simulations that miss critical behaviors and accurate simulations that produce data too slowly for modern ML techniques. Computer vision researchers point cameras at the world and generate millions of examples instantly. We fire up gem5 and wait.

Challenge 2: The Algorithm Evolution Treadmill

Machine learning algorithms evolve at breakneck speed. What’s state-of-the-art today becomes obsolete within months. This rapid evolution creates a sustainability crisis for architecture research. Should we invest months developing a system around today’s best transformer architecture, knowing it will be superseded before we finish? The computer architecture community has witnessed fifty years of algorithmic trends, from classical optimization to bio-inspired methods to deep learning. Each generation promised to be “the answer,” yet each was eventually surpassed.

The fundamental question becomes: How do we build lasting research contributions when the algorithmic foundation shifts constantly? Just because transformers revolutionized natural language processing doesn’t mean they’re optimal for cache replacement policies or instruction scheduling. Yet we lack systematic methodologies for matching algorithms to architecture problems. Too often, we apply whatever is currently popular without rigorous frameworks for evaluation.

Challenge 3: The Tools Infrastructure Gap

We have incredible tools like gem5, but they were designed for human architects, not AI agents.gem5 is a remarkable achievement, a full system simulator supporting multiple ISAs and detailed modeling. See the gem5 project and its foundational paper. However, its APIs weren’t designed for the rapid experimentation and massive data generation that modern ML demands. Gem5 excels at detailed simulation but wasn’t built for the rapid iteration and massive data generation that modern ML requires. Where’s our equivalent of TensorFlow or PyTorch for architecture research? Where are the standardized APIs that let AI agents interact with simulators, synthesizers, and place and route tools seamlessly?

The infrastructure gap extends beyond simulation. We need environments where AI agents can learn and experiment safely, where they can try radical designs without requiring months of silicon fabrication to validate ideas. The tools that enabled the deep learning revolution don’t exist for architecture yet.

As one student insightfully noted, we need “a ‘gymnasium’ for testing algorithms on a standardized benchmark of curated datasets” that would enable “academia and industry to collaboratively accelerate progress.” This vision of shared infrastructure (complete with challenges, competitions, and leaderboards) echoes successful models from other ML domains but remains conspicuously absent in computer architecture.

Challenge 4: The Reproducibility Crisis

Here’s an uncomfortable truth that emerged from our discussion: approximately 70 to 80% of papers in our field struggle with reproducibility, a figure that aligns with broader studies of computational research, but feels particularly acute in architecture where industrial adoption demands rock solid reliability. We’re excited about publishing interesting nuggets, but we punt on the engineering rigor that industry demands. When engineers receive exotic technology from academia, they often reject it because they can’t consistently reproduce the claimed results across diverse real world scenarios.

Consider floorplanning research. Papers often evaluate on carefully selected netlists with well-defined characteristics. But real systems have messy, continuously changing requirements. Industrial engineers need methods that work robustly across this variation, not just on the specific benchmarks that make papers look good. We need to move from one-shot optimization to continuous learning systems that adapt as requirements evolve.

Challenge 5: Real-World Robustness and Safety

Academic research typically optimizes for clean, well-defined problems. But real systems are messy. Workloads change, environmental conditions vary, and requirements evolve continuously. We need AI systems that handle this uncertainty gracefully, that degrade gradually rather than failing catastrophically when encountering scenarios outside their training distribution.

The safety and verification challenges multiply when AI agents make architectural decisions. How do we ensure an AI-designed cache hierarchy won’t have subtle correctness bugs? How do we verify that an AI-generated instruction scheduler preserves program semantics? These aren’t just performance questions; they’re fundamental correctness requirements that other AI domains rarely face.

The Cascade Effect: How Challenges Compound

These five challenges don’t exist in isolation—they cascade. Poor datasets lead researchers to chase algorithmic novelty instead of addressing fundamental data quality. Inadequate tools force researchers into reproducibility shortcuts. Each challenge makes the others harder to solve, creating a feedback loop that has kept Architecture 2.0 perpetually ‘five years away.’

This compound effect resonates with students’ observations about domain-specific systems. One student particularly highlighted the connection to Hennessy’s vision: “Future AI systems that become commercial will most likely have a sort of bespoke subsystem for individual tasks.” This modularity might be key to breaking the cascade—allowing progress in isolated domains without waiting for universal solutions.

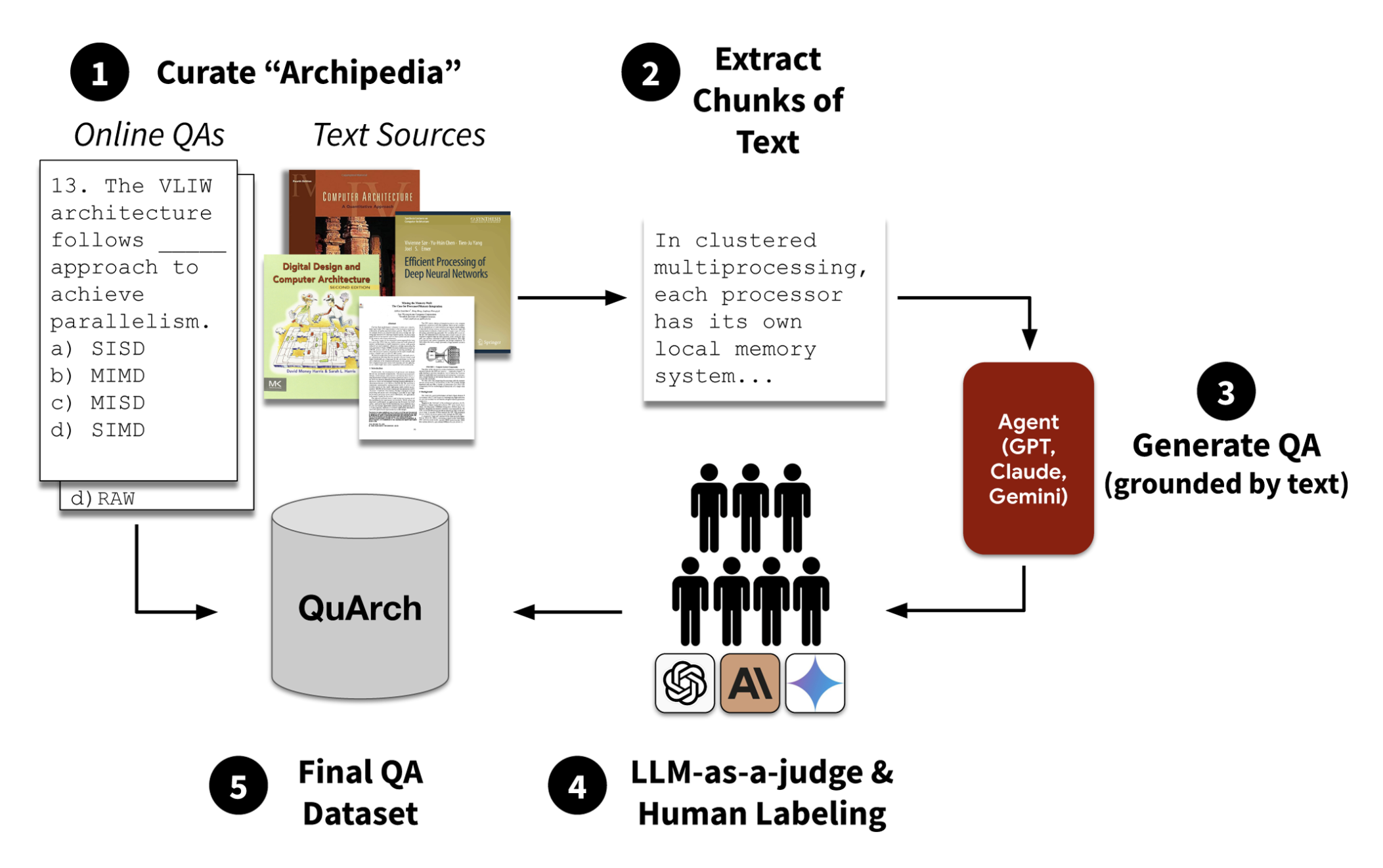

Data as the Rocket Fuel: The QuArch Experience

Given these challenges, we focused the latter part of class on the most fundamental element: data. Data is the rocket fuel of AI, and if we get this wrong, everything else fails. This brought us to a deep dive into the QuArch dataset project, led by Shvetank Prakash, which represents one of the first domain-specific datasets for computer architecture.

The Domain Expert Problem: Computer architecture spans an enormous range of expertise, from cache coherence protocols to memory controllers to compiler optimizations. Finding experts who understand all these areas is nearly impossible. Even when we found experts, their knowledge varied dramatically. An expert in processor design might struggle with networking protocols or storage systems. This expertise variation directly affects data quality because different experts interpret the same architectural scenario differently.

The Labeling Consistency Crisis: We initially used undergraduate students to help with data labeling, thinking we could train them on the basics. The results were sobering. Students produced inconsistent labels even on seemingly straightforward questions. When we elevated to graduate students and eventually faculty experts, consistency improved but didn’t disappear. Even experts disagree on architectural trade-offs because the field includes genuinely subjective design decisions.

The Expert Shortage Reality: Quality experts are scarce and expensive. They have day jobs, research agendas, and competing priorities. Incentive alignment becomes critical: Why should a senior architect spend hours labeling training data for someone else’s research? The community effort versus in-house building trade-off becomes stark when you realize that high-quality experts can’t scale to dataset sizes that modern ML demands.

The Verification Paradox: How do you verify the quality of expert-labeled data when experts disagree? In computer vision, you can spot-check labels against reality. In architecture, “ground truth” often doesn’t exist because optimal solutions depend on workload assumptions, power budgets, and design constraints that vary by application.

These practical realities shaped QuArch’s design and highlighted why building domain-specific datasets for architecture is fundamentally harder than other domains. The dataset exists now, but scaling it to the millions of examples that would truly enable large-scale AI requires solving these human-centered challenges, not just technical ones.

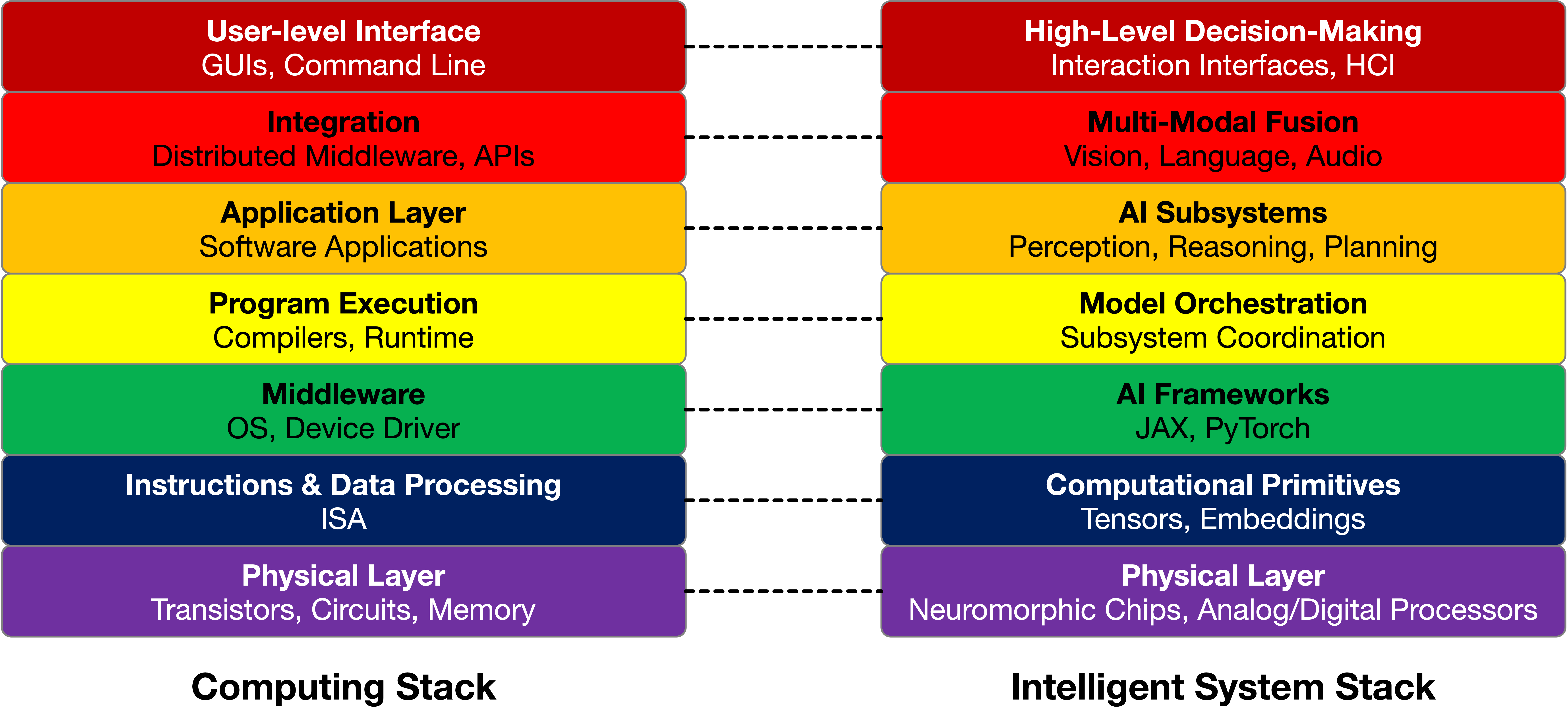

The Need for New Design Abstractions

Amir Yazdanbakhsh’s work on designing abstractions for intelligent systems provided crucial insight into why traditional architecture abstractions fail AI agents.Yazdanbakhsh’s compelling visual comparison shows how the traditional computing stack (ISA, OS, compilers) maps to an intelligent system stack (computational primitives, AI frameworks, model orchestration). This isn’t just renaming layers—it’s recognizing that AI systems need fundamentally different abstraction boundaries that enable cross-layer reasoning rather than enforcing human cognitive limitations. The abstractions we’ve used for decades were designed as cognitive crutches for human engineers. They help us decompose complex problems into manageable pieces by hiding details that humans struggle to track simultaneously.

But AI agents don’t have the same cognitive limitations. They can potentially reason about interactions across abstraction boundaries that humans find overwhelming. When we force AI agents to work within human-designed abstractions, we may be limiting their ability to discover truly novel solutions. The challenge becomes: How do we create abstractions that enable AI reasoning while still being useful for human understanding and verification?

This tension prompted deep reflection from students. One asked a fundamental question: “To what extent do human abstractions help or harm progress of machine learning guided approaches to complex tasks?” Another student connected this to their own research experience with reinforcement learning, noting how “carefully designed environments often act as controlled testbeds that reveal deeper behaviors,” drawing parallels to how standardized environments drive advances even when starting as “more contrived or controlled” settings.

Papers That Shaped Our Discussion

This week’s exploration drew from several foundational sources:

-

“Architecture 2.0: Foundations of Artificial Intelligence Agents for Modern Computer System Design” - This paper articulates the five fundamental challenges we explored and provides the theoretical framework for understanding why Architecture 2.0 requires new approaches to data, algorithms, tools, validation, and reproducibility.

-

“QuArch: A Question-Answering Dataset for AI Agents in Computer Architecture” - Our deep dive into the practical challenges of dataset construction revealed that the paper’s clean final result masks enormous engineering challenges in expert coordination, label consistency, and quality verification.

-

“A Computer Architect’s Guide to Designing Abstractions for Intelligent Systems” (Amir Yazdanbakhsh) - This work challenged us to rethink the abstraction boundaries that have guided computer architecture for decades, asking whether AI agents need fundamentally different ways of decomposing design problems.

Student Perspectives: Where Will Automation Strike First?

Our class survey revealed fascinating divergence in how students view the automation timeline. While some believe “code generation is already pretty advanced” and will be refined further, others argue that debugging represents the more tractable near-term target. As one student articulated: “Debugging has clear problems with clear answers. It is not a matter of ‘Depend’ to debug software designs.”

A particularly nuanced perspective emerged around the evolution pathway: “Code generation → debugging → optimization.” The reasoning is compelling—since “most problems presently with AI generated code involve some form of debugging, if a software design task can master this before giving a final answer, then it paves the way towards ML automated performance optimizations.”

Interestingly, several students with industry experience suggested compiler optimization as the most likely candidate for near-term automation. “ML can analyze large numbers of code paths and quickly discover optimization strategies that humans might miss,” one noted, adding that “compilers sit at the intersection of hardware and software, so even small gains in efficiency can scale across many applications.”

Looking Ahead: Why We Start with Software

Having established this foundation of challenges, we’re ready to begin our three-phase journey through the computing stack. Next week, we start with AI for Software, and this choice is deliberate. Code is the most accessible entry point for understanding how AI can transform system design. Students already interact with code generation tools like GitHub Copilot and ChatGPT, providing familiar ground for exploring deeper questions.

Software also offers the cleanest separation between correctness and optimality. A program either produces the right output or it doesn’t, but among correct programs, there are infinite optimization possibilities. This clarity makes it easier to understand how AI can move beyond traditional approaches without getting lost in the verification challenges that plague hardware design.

As we progress from software to architecture to chip design, we’ll see how these five fundamental challenges manifest differently at each layer. The dataset problems become more complex, the tools more specialized, and the verification requirements more stringent. But the core insight remains: we’re not just applying AI to existing design processes. We’re reimagining how design happens when the cognitive limitations that shaped our current methodologies no longer apply.

Students are already connecting these concepts to their research domains. One observed how “efficiency bottlenecks often dictate what research is even possible,” particularly in ML workflows where “the cost of efficient inference scheduling—both for rollout generation and reward computation—often dominates the training pipeline.” Another highlighted the self-referential opportunity: “Can models help decide which rollouts to prioritize, or how to allocate compute across competing objectives?”

The next generation of computer architects will need to navigate all five challenges simultaneously. Success requires both deep technical understanding and the wisdom to know when human intuition remains irreplaceable. As one student succinctly put it: “Progress in ML-assisted computer architecture depends less on new algorithms and more on building high quality shared datasets and benchmarks.”

For detailed readings, slides, and materials for this week, see Week 2 in the course schedule.