Week 1: The End of an Era, The Dawn of Architecture 2.0

Moore’s Law is dying. Dennard scaling ended years ago.Dennard scaling, formulated by Robert Dennard at IBM in 1974, observed that as transistors became smaller, their switching voltage and current could be reduced proportionally, keeping power density roughly constant. This meant each new generation delivered faster processors without exponentially increasing power consumption. When this scaling broke down around 2006 due to quantum effects and leakage currents, we could no longer simply make processors faster, leading to the multicore era and today’s push toward specialized accelerators. See the original 1974 paper and Bohr’s 2017 analysis of scaling trends and innovations beyond traditional MOSFET scaling. Traditional computer architecture is hitting walls that fifty years of exponential improvement never prepared us for. So why are we launching a graduate seminar on AI driven architecture design right now?

The timing is no coincidence. We stand at an unprecedented convergence of necessity and opportunity. Traditional approaches are hitting fundamental walls. Moore’s Law is slowing. Dennard scaling has ended. The complexity of modern systems has exploded beyond human comprehension. At the same time, AI capabilities have reached a point where they can meaningfully contribute to system design. This convergence isn’t about following a trend. It’s about recognizing that the field of computer architecture must evolve or risk stagnation.

The enthusiasm for this topic was immediately evident in our classroom’s composition. Students arrived from remarkably diverse backgrounds: computer architecture, machine learning foundations, ML systems, compilers, and programming languages. This wasn’t just interdisciplinary interest; it was recognition from across computer science that we’re approaching a fundamental inflection point. Computing has been the foundation of technological progress for fifty years, and we’ve taken exponential improvements for granted. Now, with the end of easy scaling and the slowing of Moore’s Law, every subfield recognizes that the free lunch is over.

During our first class discussion, a student from our ML systems cohort (someone who’d spent the previous semester optimizing transformer inference) asked pointedly: “Aren’t we just automating what architects already do?” The answer revealed the heart of Architecture 2.0. We’re not automating existing processes but enabling entirely new design methodologies that were previously impossible. When design spaces contain 10^14 to 10^2300 configurations, traditional human guided exploration becomes not just inefficient but fundamentally inadequate. To put this in perspective: if you evaluated one design configuration every nanosecond, exploring 10^14 possibilities would take over three years. For 10^2300 configurations, you’d need more time than has elapsed since the Big Bang. By a factor larger than the number of atoms in the observable universe.

The End of an Era

Hennessy and Patterson’s 2017 Turing Award lecture marked a watershed moment—the architects of RISC and modern computer architecture declaring that the old paradigms were insufficient. Their call for domain-specific architectures directly influenced the creation of this course, as the challenge I see is how do we do that automation without a whack-a-mole approach of designing one domain at a time.

For decades, computer systems innovation followed what we term the TAO framework: Technology innovation (driven by Moore’s Law), Architecture innovation (exploiting parallelism), and Optimization (through compiler advances and hardware-software co-design). This approach served the field well when design spaces remained tractable and human intuition could effectively guide solution exploration.

However, we now face fundamental technological constraints that demand new approaches. Moore’s Law continues to decelerate, Dennard scaling has effectively ended, and we confront the reality of dark silicon with diminishing returns from traditional optimization strategies. As Hennessy and Patterson have been advocating in their work on domain-specific architectures, we have entered an era where each application domain requires specialized architectural solutions.

Why This Moment Matters

Three converging forces make this the critical moment for Architecture 2.0.

We face a demand explosion. Every major application domain now requires specialized hardware, from large language models to autonomous vehicles. The era of one size fits all computing is definitively over. Companies are designing custom chips for everything from cryptocurrency mining to video transcoding. This specialization demand is creating more design work than our industry has architects to handle.

We’re experiencing a talent crisis. Training a competent computer architect takes years, but the demand for specialized hardware is growing exponentially. We simply cannot train human architects fast enough to meet the need. In class, we discussed how major tech companies are competing fiercely for the same small pool of experienced architects, driving salaries sky high while projects remain understaffed.

We’ve reached an AI inflection point. For the first time, AI systems can actually understand code, reason about performance, and even generate functional designs. This isn’t theoretical. Students in the class have already used GitHub Copilot, ChatGPT, and other tools in their own work. The question isn’t whether AI will transform architecture. It’s how quickly we can harness it effectively.

The Moonshot Moment

What we’re experiencing is what I call a “perfect storm” for innovation, reminiscent of the thinking that drove Google X’s most ambitious projects. The formula for a moonshot, as Google X demonstrated, requires four elements: a massive problem affecting millions, a radical solution that seems impossible, a breakthrough technology that makes it newly feasible, and the audacity to pursue it. We have all four.

The massive problem is clear: we need exponential improvements in computing efficiency but the traditional paths are blocked. The radical solution is Architecture 2.0, where AI agents design systems beyond human cognitive limits. The breakthrough technology is the recent emergence of large language models and code-understanding AI. And the audacity? That’s what brings us together in this classroom.

This isn’t incremental improvement. We’re talking about fundamentally reimagining how computer systems are designed, moving from human-crafted heuristics to AI-discovered optimizations that no human would ever conceive. Google X showed us that moonshots succeed when impossible-seeming problems meet newly-possible technologies. That intersection is exactly where we stand today.

The TAOS Framework: Adding Specialization

This evolution brings us to TAOS, extending TAO with a crucial fourth pillar: Specialization. During our discussion, I emphasized that specialization isn’t just another optimization technique; it’s a fundamental shift in how we approach design.

Modern design spaces contain between 10^14 and 10^2300 possible configurations. A student captured the implications perfectly: “So we’re not searching for the needle in the haystack—we’re searching for the right needle in a universe of haystacks.” Exactly. Traditional methodologies that rely on human intuition become not just slow but fundamentally impossible at this scale.

The Vision for Agentic Design

Consider the transformative potential: natural language specifications directly translated into optimized hardware implementations. For instance, requesting “a custom 64-bit RISC-V processor with full vector extension support, optimized for less than 3 Watt TDP in a 7nm LP process node.” This represents not speculative fiction but the tangible direction of our field, where AI agents handle the complexity of translating high-level requirements into detailed implementations.

Papers That Shaped Our Discussion

Our exploration this week drew primarily from two foundational papers that establish the Architecture 2.0 vision.

Architecture 2.0: Foundations of Artificial Intelligence Agents for Modern Computer System Design establishes the theoretical framework for AI driven architecture design. The authors present compelling evidence that modern design spaces contain between 10^14 and 10^2300 possible configurations, a complexity that demands AI assistance. They introduce the TAO to TAOS evolution, where Specialization becomes the critical fourth pillar enabling domain specific optimizations at unprecedented scales.

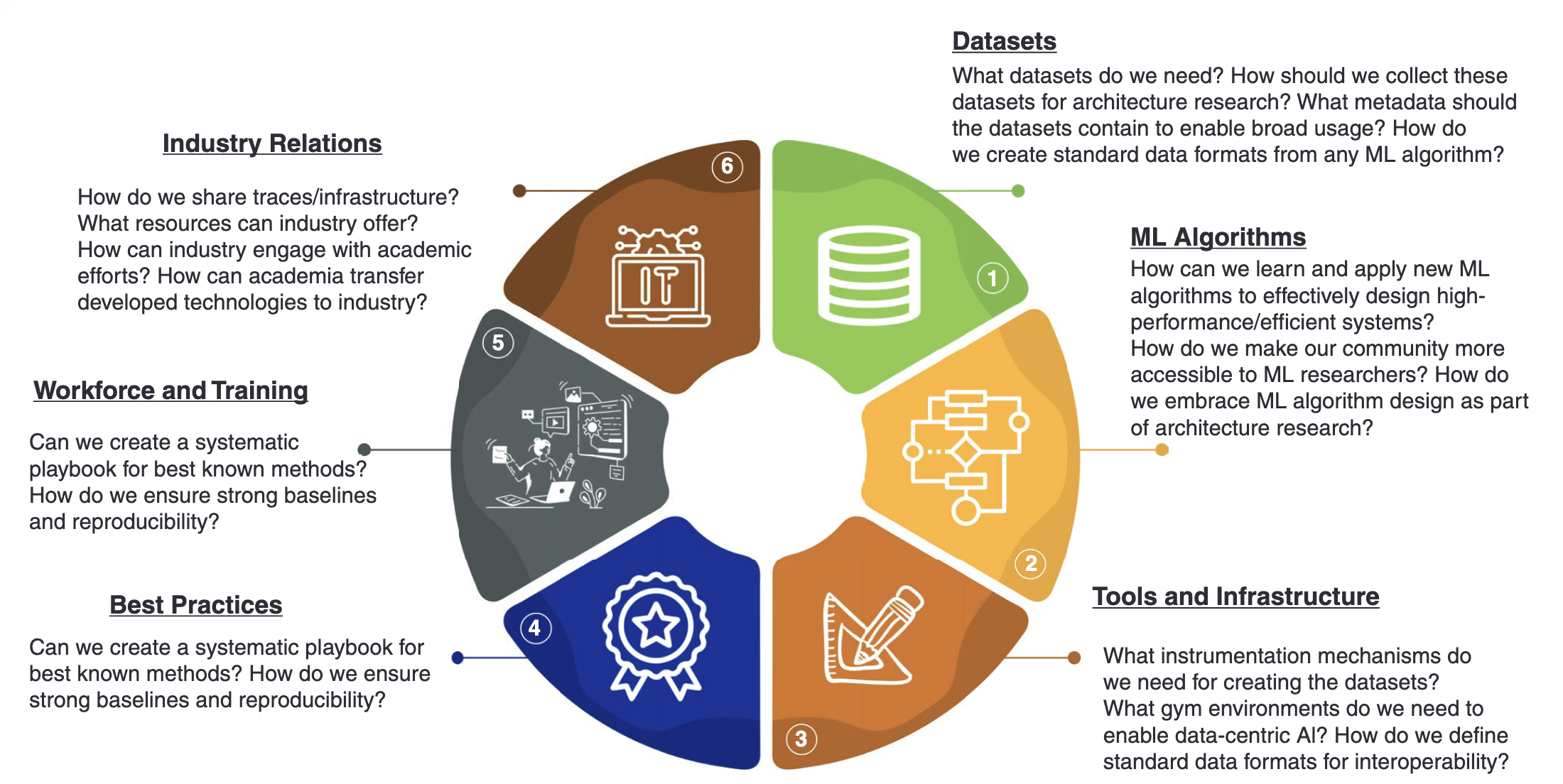

Architecture 2.0: Why Computer Architects Need a Data-Centric AI Gymnasium addresses the critical infrastructure challenge. The authors propose a collaborative platform modeled after OpenAI Gym, where researchers can share simulators, datasets, and benchmarks. Key insight: the lack of large, representative public datasets remains our field’s biggest bottleneck. The paper identifies specific opportunities where AI already shows promise: memory controller optimization, resource allocation, compiler optimization, cache allocation, and scheduling decisions.

Why We Structured the Course Across the Full Stack

A student asked why we organized the course into three distinct phases: AI for Software, AI for Architecture, and AI for Chip Design. The answer gets to the heart of what makes this moment unique.

Traditional computer science education treats these as separate domains with clean abstractions between them. Those abstractions were created as a coping mechanism for human engineers to manage complexity. But these boundaries are artifacts of human cognitive limitations, not fundamental properties of computing systems. When we limit AI agents to operating within these traditional silos, we guarantee inefficiency.

My own journey through this field has spanned compilers, microarchitecture design, mobile SoC development, embedded IoT systems, machine learning infrastructure, and most recently, embodied AI.This journey from Intel’s compiler team to Google’s mobile chips to Harvard’s AI research reflects how rapidly our field has evolved and how the boundaries between traditionally separate domains continue to blur. See my research trajectory. The consistent lesson across all these domains is that the most significant opportunities for optimization lie at the interfaces. A compiler decision affects microarchitecture behavior. Architecture choices constrain software optimization. Physical design limitations ripple up through the entire stack.

Future AI agents won’t respect our artificial boundaries. They’ll explore design spaces that span software optimization, architectural innovation, and physical implementation simultaneously. If we don’t train ourselves to think across these layers, if we don’t expose these interactions in our teaching, we’ll miss the most transformative opportunities. The agents that will revolutionize computing won’t be constrained to optimizing within a single layer; they’ll discover solutions that require coordinated changes across the entire stack.

This is why every student in this class, regardless of their home discipline, needs exposure to all three phases. The compiler expert needs to understand how their optimizations affect chip area and power. The architecture specialist needs to grasp how software workloads drive their design decisions. The chip designer needs to see how physical constraints propagate up to software performance. Only by understanding the full stack can we prepare for a future where AI agents operate without our self-imposed boundaries.

The Generative AI Difference

A critical question emerged near the end of class: “Machine learning has been used in computer systems for years. What makes Architecture 2.0 different?” This gets to a fundamental distinction we’ll explore deeply next week.

For the past decade, we’ve applied traditional machine learning to systems problems. These approaches were primarily predictive: branch predictors using neural networks, learned index structures, ML-driven cache replacement policies. These were valuable but fundamentally limited. They could optimize within existing paradigms but couldn’t imagine new ones. They could predict patterns but couldn’t generate novel solutions.

We now live in the generative AI era, and this changes everything. Traditional ML could tell you which cache line to evict. Generative AI can design entirely new cache hierarchies. Traditional ML could predict branch outcomes. Generative AI can rewrite the code to eliminate branches entirely. Traditional ML optimized parameters within fixed architectures. Generative AI can propose architectural innovations no human has conceived.

This isn’t just a quantitative improvement. It’s a qualitative transformation. When an AI system can generate RTL code, propose new instruction set extensions, or design custom accelerators from natural language specifications, we’re not just optimizing existing systems. We’re enabling a fundamentally new design methodology. The shift from predictive to generative AI is what makes Architecture 2.0 possible.

Looking Ahead

Next week, we will dive deeper into this distinction, examining how generative AI fundamentally differs from the optimization and prediction techniques we’ve used in systems for years. We’ll explore the QuArch dataset and see how question-answering capabilities enable AI agents to reason about architectural trade-offs in ways that traditional ML never could.

As we progress through our three phases, remember that the divisions are pedagogical, not fundamental. The most exciting innovations will come from students who can think across these boundaries, just as the most powerful AI agents will be those that can generate solutions spanning the entire computing stack.

The research challenges we identified—datasets, algorithms, best practices, workforce training, and infrastructure—each present significant opportunities for contribution. The question for our field is not which single challenge to address, but how to coordinate progress across all fronts.

For detailed readings, slides, and materials for this week, see Week 1 in the course schedule.